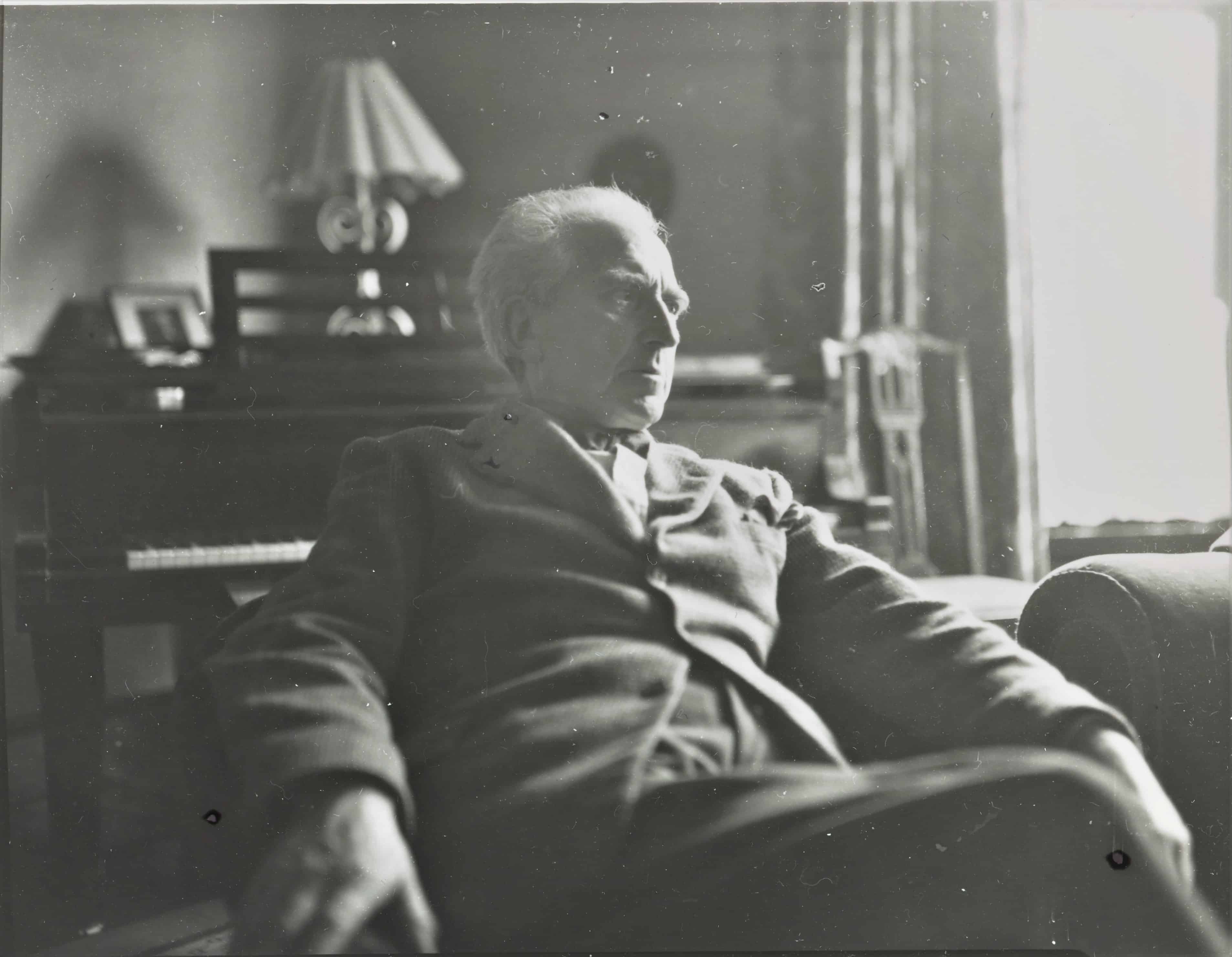

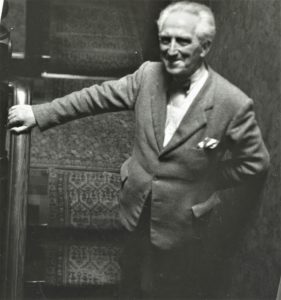

Two years after I began to record it, the first-ever album of Francis George Scott’s piano music is now available. The programme as it appears on the album (Toccata Classics TOCC 0547) happened with little planning, and by happy accident. On Sunday, 17 February 2019, Adaq Khan and I once again returned to the Turner Sims Concert Hall, Southampton, to record number four in an ongoing series of recordings by Ronald Stevenson (1928–2015). I’m not sure how we achieved the bulk of this recording on the first day, although we had planned and booked two separate days for the job. I was pleased to have got it over and done with (I get impatient when recording), but was aware of the potential waste of money in not using the session booked for the following Sunday. A bulb went on above my head: I had recently learnt all of Stevenson’s Eight Songs of Francis George Scott to play in a recital scarcely three weeks before. A quick bit of maths revealed that these pieces together with a recent discovery, namely original piano music of Francis George Scott’s, would add up to a full album in its own right. Home I went to practise for a week.

My awareness of Scott’s music began in late 2012, and, as with several threads running through my musical career, it was all down to Toccata Classics. I was encouraged by Martin Anderson to prepare and record Ronald Center’s piano music. At the time it was difficult to hear Center’s music because of the scarcity of recordings – but, Murray Maclachlan, in 1990, had recorded and released an interesting piano recital on Olympia, Piano Music from Scotland, inwhich he had put the Center Sonata and Six Bagatelles, Op. 6,together with two original works of Stevenson and transcriptions of eight of Francis George Scott’s songs. I wasn’t to engage properly with Scott’s music for a good few more years, but I remember listening to these pieces at the time and thinking they were worth taking seriously.

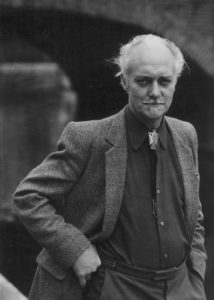

I was to recall F. G. Scott a few years later, after deciding to take on the cause of Stevenson’s piano music. At the time I was focusing on Stevenson’s Scottish-themed works, simply because, at the time, they seemed like an important discovery, as well as being fine piano pieces in their own right, and I was puzzled as to why they weren’t being taken up by other pianists. In reading what I consider one of the finest pieces of writing on Stevenson, Malcolm MacDonald’s Ronald Stevenson: A Musical Biography, written to mark Stevenson’s 60th birthday (National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh, 1989), I found Scott’s name again, now with considerable emphasis on how important a figure he had been to Stevenson in inspiring him towards cultivating a consciously ‘Scottish’ style of composition – he seemed to have been a prophet of the kind of Scottish music Stevenson wished to create.

To gain a better understanding of this influence, I went looking for Scott’s music, and found Moonstruck,a recital of his songs recorded for Signum Classics (SIGCD096) by Lisa Milne, Roderick Williams and Iain Burnside. It was the turning point for me. Initially. I thought many of these songs were fine settings of Scottish folksongs – but they are all, every one of them, original compositions, and, for me, they cry out for just about every superlative I can think of. Scott assimilated the folk-music of the western highlands and the pioborachead (classical music of the Great Highland Bagpipe) so thoroughly so as to transliterate it into a western classical idiom, in a way that no one had done before. Some will argue that Hamish MacCunn and other nineteenth-century composers aim to do as much, but I don’t think it was ever done in quite the way Scott managed.

Soon after, I discovered Maurice Lindsay’s 1980 biography of Scott, Francis George Scott and the Scottish Renaissance (Paul Harris, Edinburgh; out of print) – still the only text of any length and depth on the composer which also explores, inter alia, his literary influence on Hugh MacDiarmid. I was pleased to find that Lindsay briefly discusses some piano pieces, all miniatures, and so it was only a matter of time before I went looking for those as well. It’s a curiously critical book (in the negative sense), which is disappointing, given that it’s the only full biography of the composer in existence, but invaluable for the raw facts of his life and work contained therein. Still, Scott deserves a better book than this one.

None of Scott’s piano music is published. But to my unalloyed delight, I discovered that the Scottish Music Centre in Glasgow holds the manuscripts, of which I could buy facsimiles – and I bought everything I could. I played through it all, and decided that I could use much of it in recitals and, perhaps, even include it in a future recording project. And here we are now.

This album begins with those eight Stevenson transcriptions of Scott’s songs. They point to the backbone of Scott’s output: the corpus of songs which is his most important output. In their original form they set texts of MacDiarmid and Burns, and the booklet essay goes to some length to explain the relationship between the text and the music, so as to offer a programme to those listening to them in their transcribed form.

The album then goes on to the real reason it was made: more than 60 short album-leaves and miniatures, all within the grasp of the amateur pianist. They are charming, moving, beautiful, amusing, enigmatic – and often unfinished. Many of them were clearly sketches, and together add up to being a musical scrapbook of ideas which could have been developed into bigger pieces, had Scott been so inclined. They are a precious document of the musical musings of an original, pioneering mind. They should be published, and soon.

I owe thanks to a number of people and institutions:

- The first is Alan Riach, Professor of Scottish Literature at Glasgow University. After the piano recital in Glasgow for which I learned Stevenson’s Eight Songs of F. G. Scott Alan came up to me and said that he would be keen to contribute in any way to any further work I might do on Scott. I took him at his word and, later, asked him to write an essay on Scott for the (40-page!) album booklet. What he sent me is a terrific appraisal of the man and his achievement, and it adds to the small but growing body of writing on this fine musician. Alan also happens to be a major figure in the Scottish literary world: he is a poet in his own right, as well as being an authority on Hugh MacDiarmid, among other things, and has written many articles for The National on art, literature and history. It’s humbling to have had him on board with this project and I very much hope we continue to collaborate.

- I must thank Dr James Reid Baxter, who funded the Ronald Stevenson recording sessions out of which this album happily emerged, not only for his ongoing benevolence but for being delighted that his funds could be stretched to produce a surprise recording! Thanks, Jim, always.

- My gratitude goes also to Martin Anderson of Toccata Classics for being so supportive of this project, and (I hope!) many others to come (there will be quite a few). Although we are both Scots, our joint promotion of Scottish music is not because it is Scots but because it is more than good enough to deserve international attention. I particularly appreciate Martin’s editorial guidance, which forces me to think more carefully about what I try to convey. I’m no professional writer and only have a mediocre Scottish Higher in English, and so his keeping me in check is both valued and necessary.

- Thanks, too, to Samantha Melville, who propped me up while I struggled to write the booklet essay and get everything finished amidst the pressing demands of online teaching this past summer.

- Turner Sims Concert Hall, for always being very reasonable and easy to deal with. Their piano was in particularly good form this time round, having just had Steinway’s technicians overhaul it a few weeks previously.

- The Scottish Music Centre, Glasgow – this project would have been impossible had such a facility not existed. It’s strange that no other pianist has already undertaken a systematic exploration of Scottish piano music, given the abundance of material that the SMC holds.

- Adaq Khan – for indulging my whim to record a bonus album, being patient, and for capturing the sound beautifully, not to mention all the editing. Working with him is always a rewarding experience.

Future plans with Toccata Classics? Ronald Stevenson: Piano Music, Volume 5 (TOCC 0606) recorded late this summer (a programme of transcriptions of Purcell, Delius and van Dieren), and scheduled for release in 2021. Then the rest of Ronald Center’s piano music, as much of William Moonie’s piano music as I can lay my hands on, and all of William Wordsworth’s piano output, in parallel with the exploration of his orchestral music underway on Toccata Classics. All being well, you’ll be able to hear the outcome of these adventures over the next year or two.

Christopher Guild Recordings on Toccata Classics

-

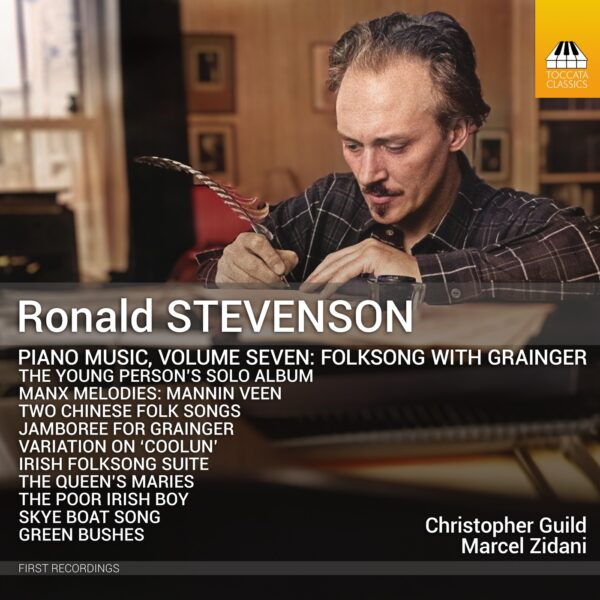

Ronald Stevenson: Piano Music, Volume Seven – Folksongs with Grainger

Ronald Stevenson: Piano Music, Volume Seven – Folksongs with Grainger -

Ronald Center: Instrumental and Chamber Music, Volume Three

Ronald Center: Instrumental and Chamber Music, Volume Three -

William Wordsworth: Complete Music for Solo Piano

William Wordsworth: Complete Music for Solo Piano -

Ronald Stevenson: Piano Music, Volume Six

Ronald Stevenson: Piano Music, Volume Six -

William Beaton Moonie: Chamber and Instrumental Music, Vol. One: Music for Solo Piano

William Beaton Moonie: Chamber and Instrumental Music, Vol. One: Music for Solo Piano -

Ronald Stevenson: Piano Music, Volume Five

Ronald Stevenson: Piano Music, Volume Five -

Francis George Scott: Complete Music for Solo Piano

Francis George Scott: Complete Music for Solo Piano -

Ronald Stevenson: Piano Music, Volume Four

Ronald Stevenson: Piano Music, Volume Four -

Ronald Stevenson: Piano Music, Volume Three

Ronald Stevenson: Piano Music, Volume Three -

Ronald Stevenson: Piano Music, Volume Two

Ronald Stevenson: Piano Music, Volume Two -

Grigori Frid: Complete Music for Viola and Piano

Grigori Frid: Complete Music for Viola and Piano -

Ronald Stevenson: Piano Music, Volume One: A Celtic Album

Ronald Stevenson: Piano Music, Volume One: A Celtic Album