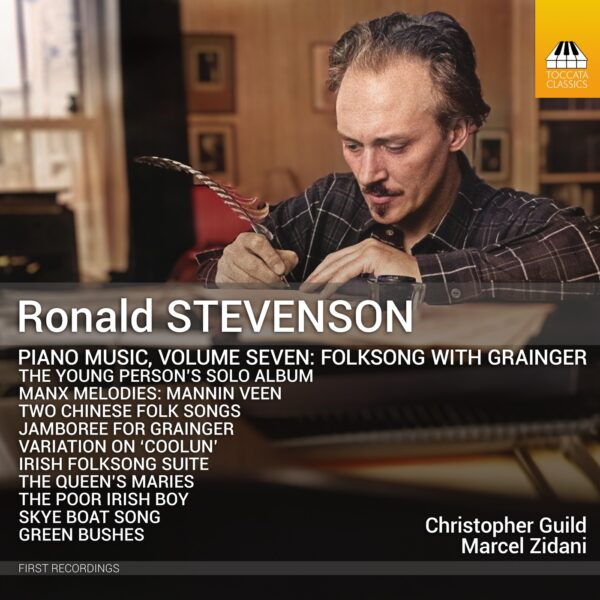

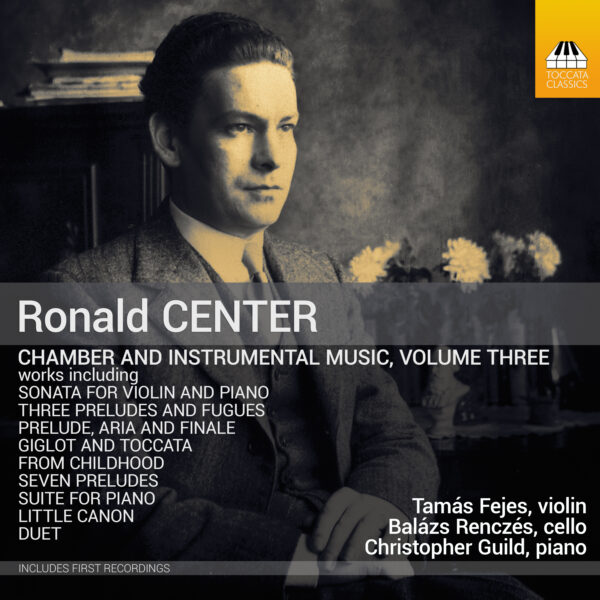

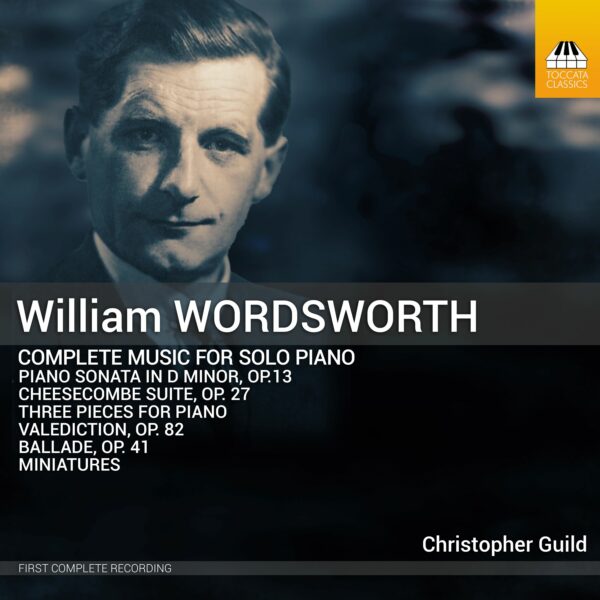

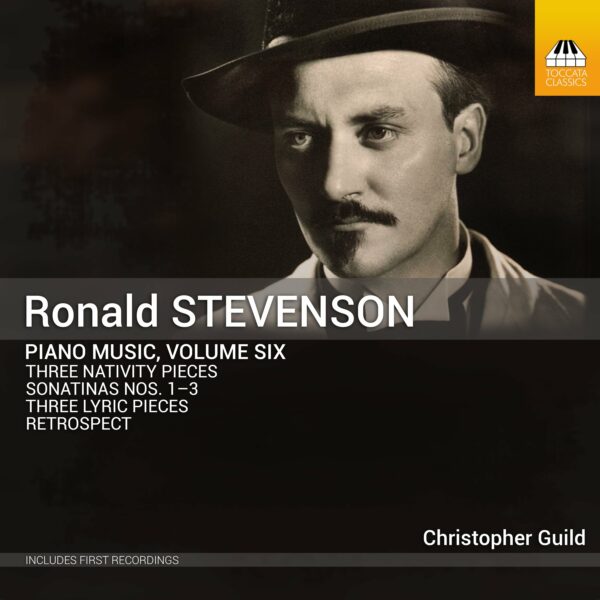

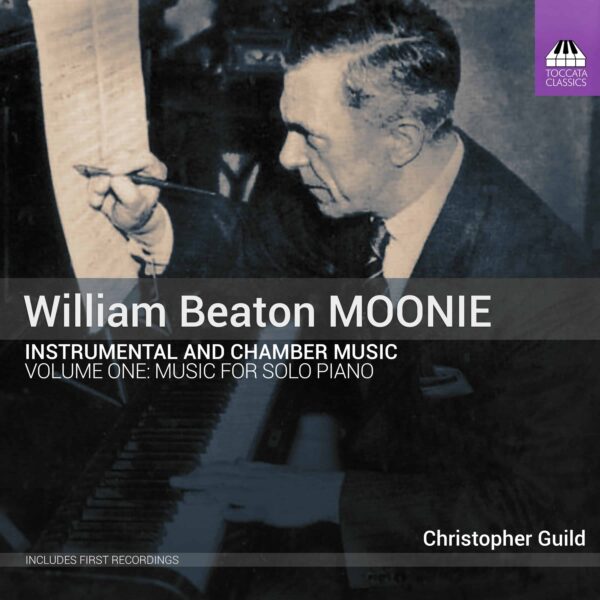

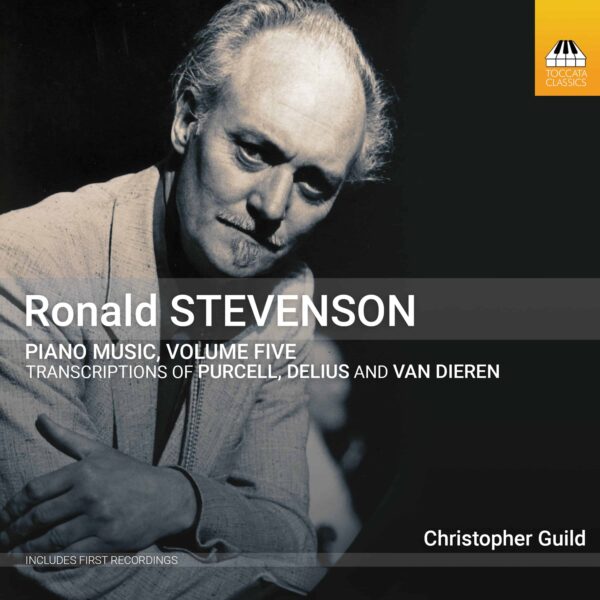

An inadvertent benefit of the lockdowns of 2020 and 2021 was that I had time to do lots of recording. I was able to record Ronald Stevenson (Piano Music, Volume Five: Transcriptions, TOCC 0606) and William Beaton Moonie (Instrumental and Chamber Music, Volume One: Music for Solo Piano, TOCC 0602), and the as-yet unreleased Ronald Center (Instrumental and Chamber Music, Volume Three, featuring the rest of the piano music, plus the Sonata for Violin and Piano) and the complete piano music of William Wordsworth. It was immensely fortunate that I was able to get on with all that, and it was a welcome diversion from all the online teaching I was doing at the time.

We are back to attending, and giving, performances now. Even so, I know several musicians who once had a busy concert schedule but who are now struggling to resume the volume of activity they once had. It’s a worrying situation for many of them, some of whom are now having seriously to rethink their careers. I haven’t given a performance of any kind since a private house-concert a month before the government announced the first lockdown in March 2020. That was a duo recital, and my last solo appearance was in December 2019 in Salisbury, where I gave a lunchtime recital of Elgar’s ‘Enigma’ Variations for solo piano (it works really well in this version!). That’s over two-and-a-half years ago. I’ve never had the busiest concert schedule, which has always suited me, but it’s nerve-wracking even to consider stepping in front of an audience again after all this time.

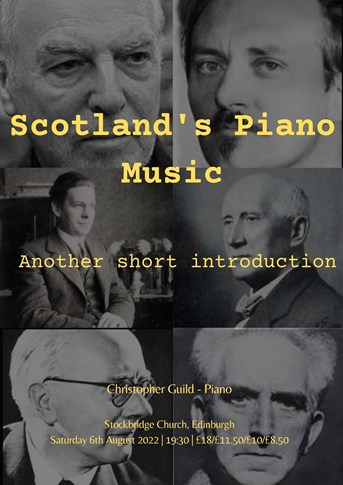

But that is what’s about to happen next month, at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival. Following on from my 2018 recital, ‘Scotland’s Piano Music: A Really Short Introduction’, I’ll be heading back up the road to the Scottish capital to give what I’ve been informally referring to as the sequel recital to that performance. ‘Scotland’s Piano Music: Another Short Introduction’ will explore piano music written by Scottish-born, Scottish-educated, Scottish-domiciled and/or ancestrally Scottish composers between the 1920s and the 1980s. It’s definitely an unusual theme for a recital, and it does, even to me, feel ‘a bit niche’. So, what’s the reason for holding this event, and why should anyone consider the idea behind it as important?

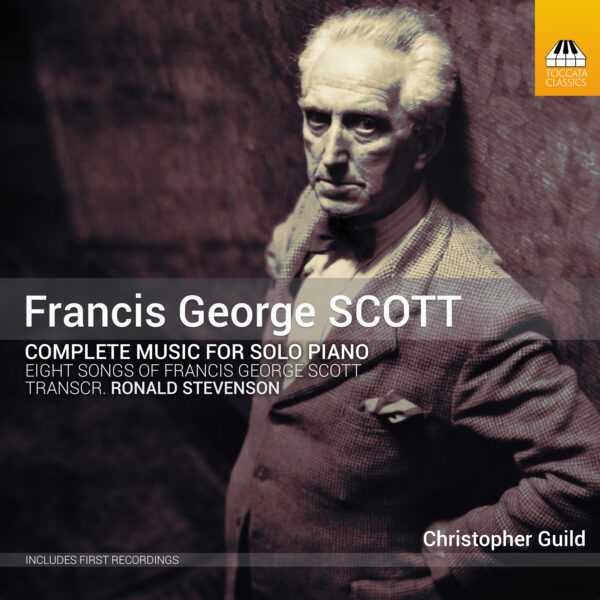

My Toccata Classics profile is, with the exception of a CD of viola and piano repertoire by the Russian Jewish composer Grigori Frid (TOCC 0330) with the violist Elena Artamonova, one of Scottish classical music. It’s become the career specialisation I never realised I was looking for. Martin Anderson, a fellow Scot (from Crieff), encouraged me in this direction when, after I wrote to him out of the blue in 2012, he suggested I take a look at Ronald Center’s piano music. It’s a keen interest that’s snowballed massively as the years have gone by. Shortly after recording my first Center album (TOCC 0179) in 2013 I discovered Ronald Stevenson’s piano music and couldn’t believe what I’d been missing. That in turn led me to discovering the frankly amazing songs by Francis George Scott, and thereby finding out that Scott wrote piano music, which in turn led me to record that very repertoire in 2019 (TOCC 0547). The latter is possibly the most significant, interesting, unusual and entirely unexpected find of my career to date, and maybe even the one I’m proudest of. I’ve yet to celebrate the album properly in the form of a live event, but watch this space.

My commitment to recording intensively over the years has resulted in my spending a lot of time and energy digging around for what other Scottish classical music there might be: mainly for the piano, of course, but also across all instrumental and vocal idioms. I am staggered by how much of it there is. We are familiar with the big names of Scottish music today, chief among whom is Sir James MacMillan. We also have major figures such as Stuart MacRae and ex-pats such as Thea Musgrave and Judith Weir. There’s a burgeoning new music scene with its origins north of the border, and much is happening there to make it a vibrant one. Scottish music today isn’t under-represented. What isunder-represented is the vast quantity of its music from the not-so-distant past. The reason for its neglect is lamentable, not because it’s the product of the minds of Scotland’s musicians, nor because it is Scottish, but because so much of it is such good music. Work of quality is enough in and of itself. The rise of Scottish nationalism is certainly turning Scots’ attention to our nation’s cultural heritage, but I’m keen to underline that it is the work itself which is important, and not necessarilyits relation to politics: if art speaks, or has meaning and validity, only when aligned to a specific cause, then it is deprived of any currency without that cause, and is thereby weak and, at the risk of inviting the ire of ethnomusicologists with the use of the word, not universal.

Why, then, is Scottish music so overlooked, if it is indeed as wonderful as I declare it to be? The music by the composers that interests me the most is, to all intents and purposes, quite conservative in its style. For example, W. B. Moonie wrote, or at least published, his surviving piano music from the 1920s onwards. Scotland was an abiding preoccupation for Moonie in his music, something expressed through free transcriptions of popular Scottish songs of the previous century, and couched in a late-Romantic style not a million miles away from those of Max Reger and Max Bruch. I mean, in the best possible sense, that his music isn’t harmonically especially adventurous. He wrote some cracking little character pieces (A Scottish Chapbook), sometimes with some biting dissonance, but in the main his music is beautifully pleasant, and lovely, and there’s nothing wrong with that. The problem was that after the First World War, the western music world was trying to put the past behind it, trying to produce a genre that was less emotion-based, less associated with the more innocent pre-war times. Moonie, and composers of his stylistic ilk, just weren’t going to be taken seriously by the cultural establishments promoting new music.

The problem was even worse after the Second World War. Ronald Center, a self-taught composer from Aberdeen who had no formal training, wrote music that on the surface sounds at times like Prokofiev, Ravel or Vaughan Williams, with some allusions to Scottish folksong and nursery rhymes thrown in. Although little of his music is dated, it is known that his earliest surviving piano pieces are from 1942, and that quite a lot of the rest was written in the 1950s. Because of his acute shyness, his inability to promote his work, his (and this is my conjecture) possible reluctance to accept criticism of work which does have a constant sense of it being intimately personal – as well as the fact that he was not attached to any institution of higher education – it is unsurprising that his work was never particularly well known. Prokofiev, Ravel and Vaughan Williams were certainly outsiders as far as the avant-garde was concerned, in a generation where Stockhausen, Cage, Boulez and others defined how it was acceptable to write music, and what could be taken seriously by the international cultural establishments. Audiences in Scotland in the mid-twentieth century were conservative. According to John Purser in his magisterial book Scotland’s Music (which is currently being revised for its third edition – hooray), the popular musical taste throughout the country in this period was for the likes of Jimmy Shand. Go figure!

Center and Moonie both pursued their careers in Scotland – Moonie did study in Germany, but returned to his native Edinburgh immediately upon completion of his musical education. F. G. Scott also chose to remain, partly for family reasons, but also because he believed in creating a brand-new future for Scotland through art. This, for him, involved being in the thick of artistic transformation in his home country: how could he possibly have achieved anything innovative while geographically removed from his roots? He, along with fellow creatives of the Scottish Literary Renaissance, who included Hugh MacDiarmid, William Johnstone and Edwin and Willa Muir, propagated a new cultural vision for the country which ran in tandem with the founding of a political party, now the Scottish National Party. Scott wrote music which had its origins in Scottish folk idioms and pibroch, but was also grounded in a post-Fauré Romanticism. He is held in high esteem in Scotland, particularly among those with an interest in song (Scott wrote hundreds of them, and they’re just brilliant), but he isn’t so well known beyond its borders.

Erik Chisholm is another Scot who sought to assimilate native cultural heritage into his music. He has been called ‘McBartók’, because of how his music has an obvious, superficial likeness to the jaggedness and modalities of much of Bartók’s. It’s a label I absolutely hate. Put ‘Mc’ or ‘Mac’ in front of anything and you disparage the seriousness of Scottish culture. It reduces its serious art to kitsch, to the artistic standard of tourist tat that one finds in the shops along the Royal Mile in Edinburgh. We must be careful not to ‘tartanise’, or cheapen, Scottish music in that fashion. Chisholm’s music has a power and a mission unparalleled by many other Scottish composers. That it has had to wait until the 21st century to be recorded and really become known is a travesty, but at least it’s now happening.

Tellingly, our nation’s composers who were never forgotten were the ones who left and never returned. Why did they leave in the first place? It has always been the case that it was considered glamorous to study music abroad, before coming home and being known as a bright young star who has travelled (although it didn’t really seem to work for Moonie). Not only that: Scotland didn’t have a conservatoire with a designated composition course, nor a university music department with discrete provision for the study of composition. Edinburgh had the Reid School of Music, and certainly under Sir Donald Tovey’s guidance many composers, including William Wordsworth, flourished. But to study composition one had to go at least as far away as England, very often to London. Hamish McCunn did so, as did John Blackwood McEwen, to name but two. McEwen is a composer who has really caught my attention of late, with his very strong influence of Debussy and Ravel throughout his later music. It’s breathtakingly beautiful stuff. My top recommendations are On Southern Hills, for solo piano, and the String Quartet No. 7, ‘Threnody’. The last movement never fails to move me to tears.

Those composers who left Scotland have, admittedly, not remained absolutely central to the classical repertoire, but nor have they been entirely forgotten. This has been interpreted by some historians as being due, in part, to anti-Scottish sentiment in the UK’s broadcast institutions (for example, the BBC). Certainly, in the post-Second World War modernist climate, being Scottish and not producing music akin to that of Elliott Carter, Jonathan Harvey or any of the other modernists would really count against you. It did help, though, if you didn’t stay in Scotland. Two of the most successful Scottish composers of the twentieth century expatriated themselves: Iain Hamilton and Thea Musgrave. They both went to America: Musgrave, originally from Edinburgh, is still there, and Glasgow-born Hamilton returned to his childhood city of London, where he died in 2000. That’s an all-too-brief account of mid-twentieth-century Scotland’s lack of success with some of its composers. It should be clear, however, that none of the above reveals any comment on the worth, on the quality, of the music that is out there. There is so much of it which is worth hearing.

And we now can. Toccata Classics is leading the way, with other big labels like Hyperion and Chandos, in promoting these wonderful Scottish composers (and a mathematician, if we include Douglas Munn, who, as well as being a fine pianist and a gifted composer, was also a professor of mathematics at the University of Stirling – his complete music for solo piano is available on TOCC 0559). Now that streaming is normal, we can find and listen to it all instantly.

What now needs to happen is for musicians like myself to start performing it all live: there is nothing like live performance. Recording is also essential for the dissemination of music across the globe, and for posterity. There is no better way of making unknown music known. But the magic of hearing this music in concert, in the moment, is irreplaceable, creating each piece anew. The communal experience of hearing all this repertoire by the likes of Ronald Center (Sonatina), Erik Chisholm (Straloch Suite), John Blackwood McEwen (On Southern Hills), John McLeod (Another Time, Another Place), William Beaton Moonie (Perthshire Echoes), F. G. Scott (Crowdieknowe) and Ronald Stevenson (Scottish Folk Music Settings for piano) together in concert, for the first time in decades, will be a very special thing indeed. So if you’d like to partake in that, and discover a part of the British Isles’ cultural heritage that’s been lying under everyone’s noses for so long without being given a voice, come along to ‘Scotland’s Piano Music: Another Short Introduction’ on Saturday, 6 August, at Stockbridge Church, Edinburgh. Tickets can be bought here. Doors on the night open at 19:00, with the lecture-recital beginning at 19:30. It’s a big programme, but you’ll leave, I hope, having learnt something, and – better still – enthusiastic to go and see what else is out there. I look forward to seeing you!