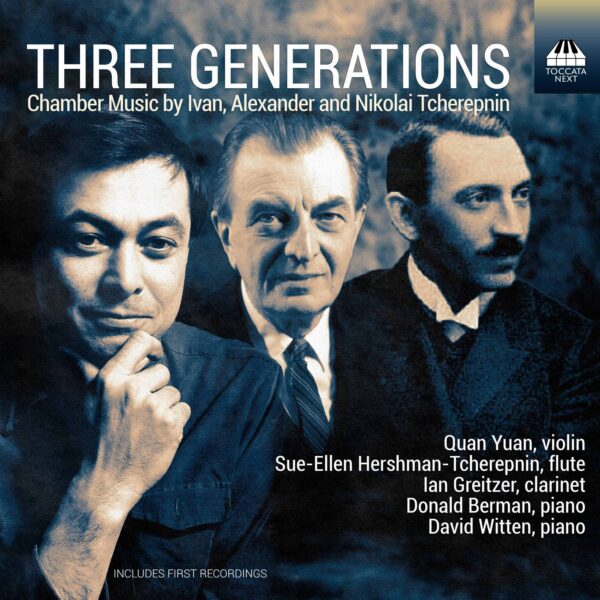

Three Generations explores music by three generations of composers from the Tcherepnin family: Ivan, Alexander and Nikolai. Each of the three wrote a wide range of scores, from solo pieces and large ensemble works to operas and ballets. This recording reveals the invaluable contribution the family made to the chamber-music literature, presenting pieces in a variety of styles, and spanning 95 years. The exceptional works for violin and piano of Nikolai and Alexander have rarely been heard. The chamber music of Ivan is represented by early as well as later works for flute, clarinet and piano. Five of these works are recorded here for the first time.

My own involvement with the Tcherepnin composers was the result of serendipity and good fortune. My close friend, the flautist Sue-Ellen Hershman-Tcherepnin, was pivotal to my discovery of the Tcherepnin family’s music. In the 1990s, Sue-Ellen married Ivan Tcherepnin (1943–98), a versatile and gifted composer who taught at Harvard University. I got to know Ivan as a composer and as a friend. When Sue-Ellen and I were invited to play in Quito, Ecuador, in 1996 for the 40th-anniversary celebration of the U.S. Fulbright Program, Ivan composed a piece for us to perform there. Our recording of this work, Pensamiento, is included on this album. As Ivan explained, ‘Pensamiento is about uniting North and South. My love of the land of Ecuador and its people is reflected in the opening, which is a mini “Condor Song”. After an encounter with the Eagle and ensuing conflicts and dramas, the Condor peacefully soars away above the highest Andean peaks’. The other work by Ivan on this recording is Cadenzas in Transition, a trio performed in a live concert by talented members of the Boston new music ensemble Dinosaur Annex. Along with Sue-Ellen, the performers are the clarinettist Ian Greitzer and the pianist Don Berman.

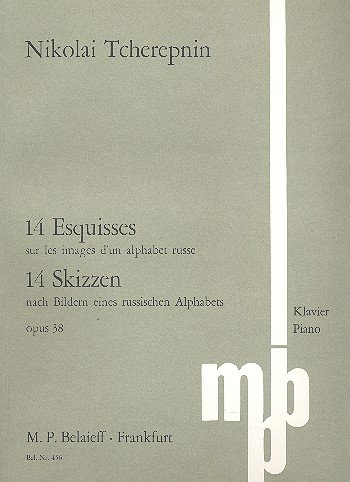

Ivan’s untimely death in 1998 was a terrible tragedy for his family and friends, and for the world of music. It was only later that I began to learn about the vast musical legacy of the earlier Tcherepnin generations. One day, Sue-Ellen and I were going through some unsorted boxes of music that had been sitting in their garage. She offered me copies of any of the piano music that I wanted. One piano score looked particularly intriguing. It was composed by Ivan’s grandfather, Nikolai Tcherepnin (1873–1945). Its title translates as ’14 Sketches on Pictures from the Russian Alphabet’. This fascinating title was a puzzle that I finally solved.

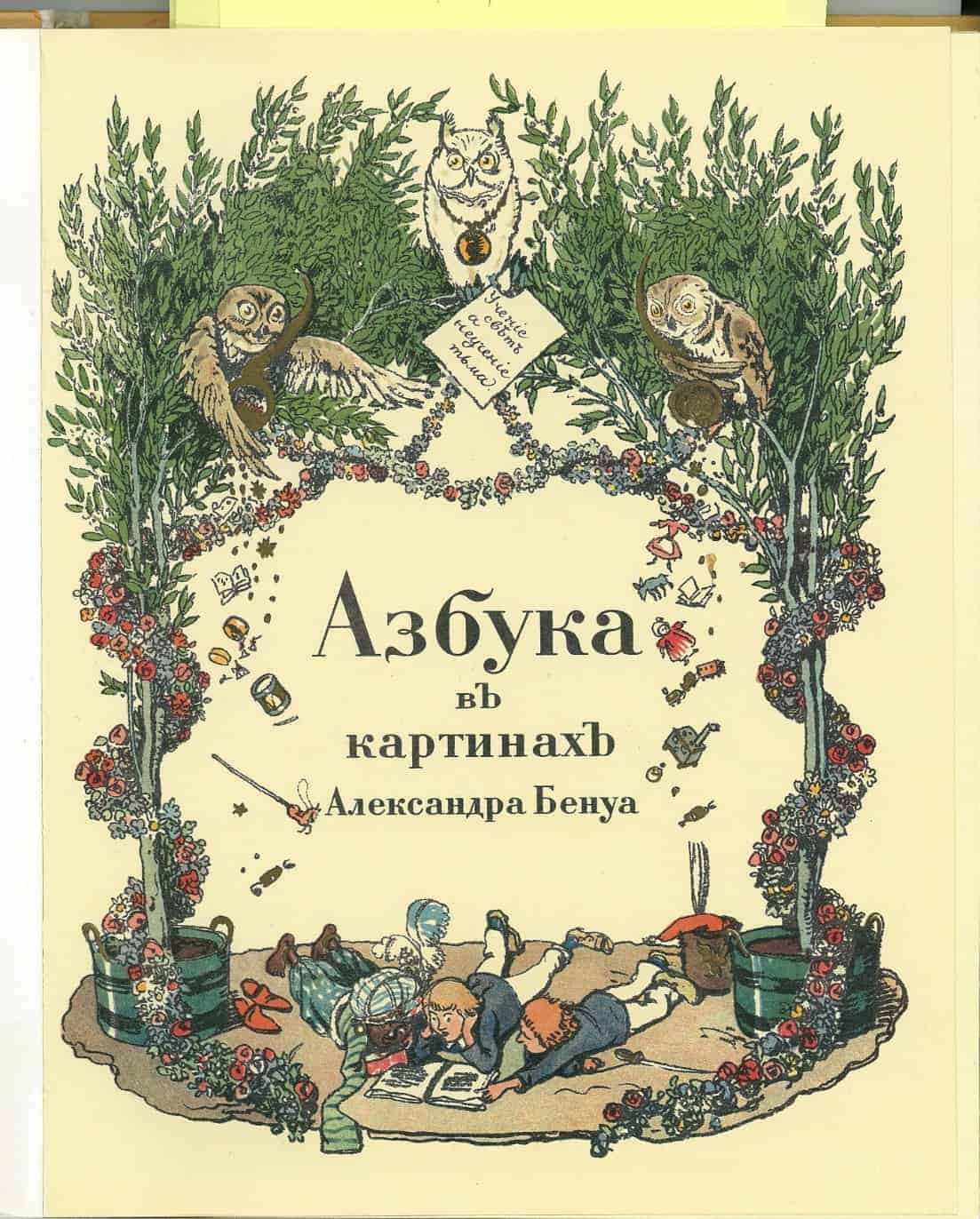

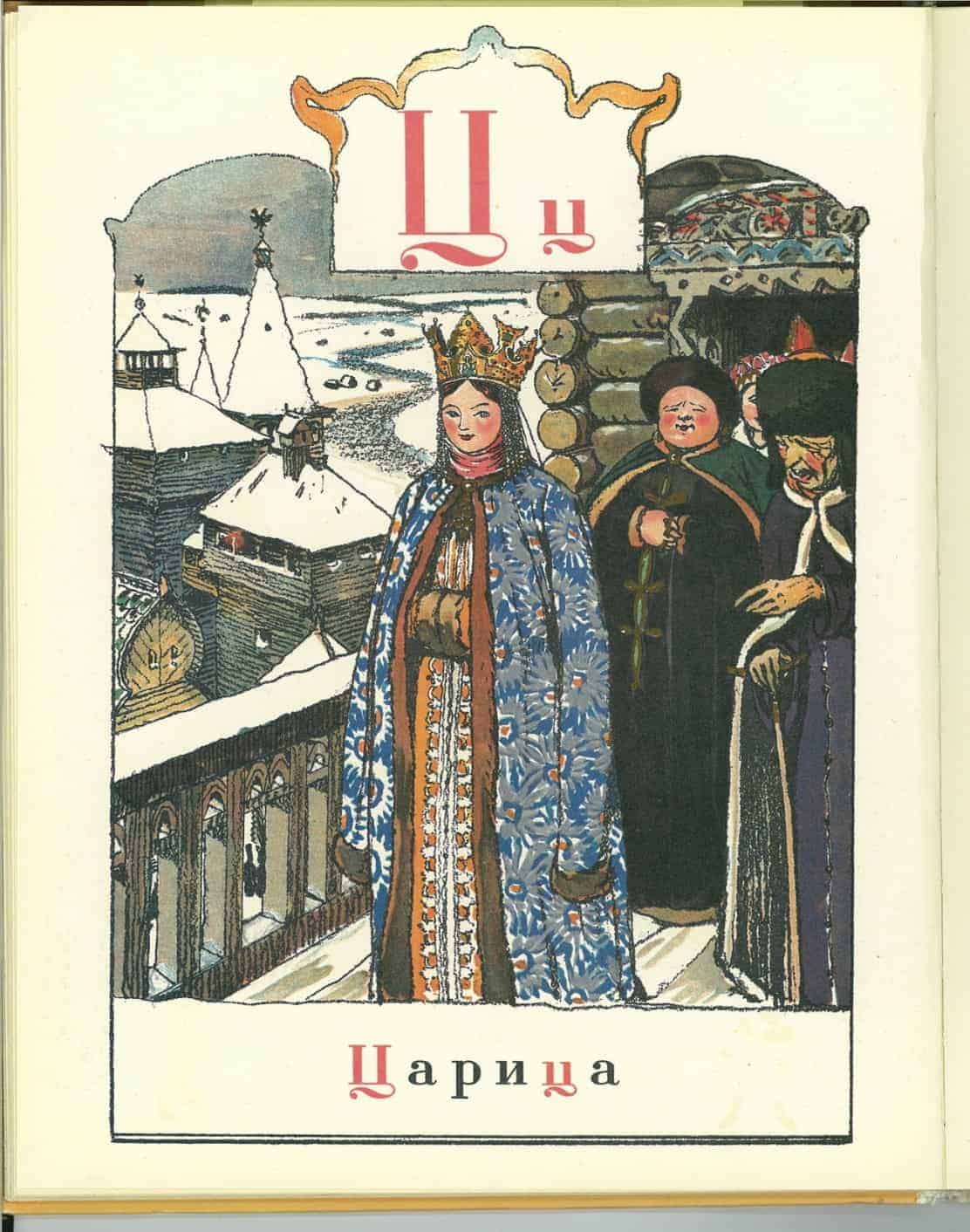

It turns out that there is a very artistic explanation for this ‘Russian Alphabet’ collection. By 1907, Nikolai Tcherepnin was part of Sergei Diaghilev’s creative circle, which was soon to become the Ballets Russes. The set designer with this group was the wonderful artist Alexander Benois. In fact, Tcherepnin was already very close to the Benois family – in 1897 he had married Marie Benois, Benois’ favourite niece. In 1903, Benois created and published for his young children an illustrated children’s book, an Alphabet Book in Pictures, where each letter of the Russian alphabet is matched with a word, and each word is beautifully illustrated with a scene from a Russian fairy tale or an image of childhood.

Tcherepnin was so taken with this book that he chose fourteen of the scenes and wrote piano sketches to illustrate them musically. And that was the collection of piano music that I found in Sue-Ellen’s garage. This music became the centrepiece of my solo recording of Nikolai Tcherepnin’s pianomusic (Toccata Classics TOCC 0117, 2011).

A few years later, contemplating a second solo album of Nikolai Tcherepnin, I played through another pile of music that I had gathered from the garage. But this time, I was more interested in some of his vocal music. There were some charming songs based on fairy tales by the Russian poet Konstantin Balmont. I resolved to find an expressive soprano whose first language was Russian and who also lived in the New York area, so that we could learn and rehearse the music together. Serendipity stepped in again – I found some videos of Elena Mindlina, a Russian-born soprano, who had moved from Saratov in Russia to Astoria in Queens. We learned and recorded 29 songs, the majority of which were set to Balmont’s poetry. These included not only his fairy tales but also sets of ancient Japanese lyrics and mystical incantations. The recording was released in 2014 (Toccata Classics TOCC 0221).

Still later, I was fortunate to get to know a remarkable violinist, Quan Yuan, who had recently married a friend of mine, the Chinese soprano Wanzhe Zhang. Quan Yuan had come from China to study violin at the Curtis Institute of Music and then at the New England Conservatory. I was eager to collaborate with him. Following further Tcherepnin research, I discovered some beautiful but relatively unknown works for violin and piano by both Nikolai Tcherepnin and his son, Alexander Tcherepnin (1899–1977).

The two works that Quan and I wanted to include by the elder Tcherepnin were Poème Lyrique and Andante and Finale, works that framed the beginning and end of his compositional career. In an autobiographical essay, Nikolai Tcherepnin wrote: ’the Poème Lyrique, Op. 9, for violin and piano was [the] piece that brought my music to the attention of European musicians, since the list of my compositions in European music-reference books typically begins with it’.1 Andante and Finale had been published posthumously but was presumably written around 1943. It includes a very humorous and energetic Finale. Indeed, if this Finale were to be orchestrated, it would certainly require a harmonica, a squeeze-box-style bayan, a brass ensemble, a piccolo and a calliope (a steam organ).

In addition to these two wonderful works by Nikolai, Quan and I also learned and recorded four works by his son, Alexander. Of the three Tcherepnin composers, Alexander had the most substantial international career and the largest compositional output. These four violin and piano works date from the 1920s. The Violin Sonata in F major, Op. 14 (1921), is dedicated to Adila d’Arányi Fachiri (1886–1962). Adila and her younger sister, Jelly, both virtuoso violinists from Hungary, were great-nieces of the legendary violinist Joseph Joachim. They settled in London, where Adila and Alexander Tcherepnin premiered this sonata in a recital on 17 November 1922.2

At this point, I feel it is blog-worthy to describe our unusual scheduling of the sessions for the violin-and-piano music on this recording. During the innocent pre-Covid days of April 2019, Quan and I recorded most of the Nikolai and Alexander Tcherepnin violin/piano works at the concert-hall of Purchase College, State University of New York, with the excellent recording engineer Joel Gordon, who travelled down from Boston to record us. Quan had been working as a member of the Met Opera Orchestra for about five years. Our busy schedules prevented us from recording the Tcherepnin violin sonata in 2019. When Covid reared its ugly head, the recording of Alexander’s sonata was delayed for much longer than we expected. Meanwhile, well into the Covid era, and with the Met Opera closed for many months, Quan and his wife Wanzhe decided to move back to China, where Quan had just been offered the position of Concertmaster with the Hangzhou Philharmonic Orchestra. But a small window of opportunity opened. In the summer of 2021, Quan and Wanzhe were coming back to the USA for just a few weeks to settle their affairs and pack up their remaining things. They would be flying back to China on 28 July 2021. So, with the help of Serendipity and her twin sister Coincidence, we were able to secure 27 July – one day before their departure – as a recording date. We booked a recital hall (this time at Drew University, Madison, New Jersey) and again secured the services of Joel Gordon, a piano tuner and a page turner. Mission accomplished.

This blog posting would not be complete without mentioning the very influential Tcherepnin Society. Alexander’s wife, the talented pianist Ming Tcherepnin, founded the Society in the late 1970s, shortly after the passing of her husband. Its mission is to promote the music of all the Tcherepnin composers. Since 1998, under the capable leadership of Benjamin Folkman, the Society has supported various international concerts and recordings. In addition to the three already mentioned, Toccata Classics also produced the first recordings of songs by Alexander Tcherepnin, performed by the talented soprano Inna Dukach and the sensitive pianist Tatyana Kebuladze. These Russian songs constitute a voluminous ’lost‘ song cycle (My Flowering Staff), previously published only in fragments, in which the original Russian lyrics had been replaced by French translations (Toccata Classics TOCC 0537, 2020).

Tatyana is currently Artist Laureate of the Tcherepnin Society. As for myself, I am pleased to say that I was invited to join the Board of the Tcherepnin Society in 2009 and I am currently its Vice-President. Further information about the Tcherepnin composers can be accessed at www.tcherepnin.com.

- 1 Nikolai Tcherepnin, Under the Canopy of my Life, unpublished autobiography in Russian, translated by John Ranck, 1942, p. 45, www.tcherepnin.com/nikolai/memoirs_nik.htm.

- 2 The sisters Adila and Jelly d’Arányi later received unusual attention when, in 1933, they attended a seance in London. Robert Schumann ‘spoke’ to them through a ouija board and asked them to search for his unpublished Violin Concerto in a European library. The Concerto was indeed recovered in the Prussian State Library in Berlin. However, as Nicolas Slonimsky later noted, ‘Schumann’s ghost spoke ungrammatical German, which aroused suspicion concerning the authenticity of the phenomenon’ (Nicolas Slonimsky, Baker’s Biographical Dictionary of Musicians, Schirmer Books, New York, eighth edition, 1992, p. 49).