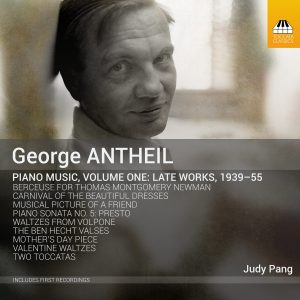

When Martin Anderson of Toccata Classics first suggested a project of music by the American composer George Antheil, I immediately thought of the typically avant-garde music for which Antheil is best known. From my student days, I particularly remembered hearing his Airplane Sonata (1922) as a slightly barmy, unruly and raucous work. Evidently, he seemed quite deserving of the famous epithet ‘The Bad Boy of Music’, which he apparently wore as a badge of pride – in 1945 he used it as the title of his autobiography. Moreover, there were so many strange details about his life that further imprinted his name into the memory – to mention a few: his placing a revolver on the piano during one of his concerts as part of his ‘Bad Boy’ image, his working with the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League to display artworks banned in Nazi Germany, his interest and expertise in female endocrinology, and his collaboration with the film star Hedy Lamarr to invent frequency-hopping spread-spectrum which functioned as a radio guidance system for torpedoes during World War II.

Martin introduced me to Mauro Piccinini, one of the world’s most prominent contributors to scholarly research on George Antheil’s life and work. Mauro proposed a chronologically ordered project of Antheil’s late piano works, and I was immediately attracted to the opportunity of unearthing so many hidden musical gems. The wheels of musical exploration were set in motion as I embarked on the discovery of an entirely unknown part of Antheil’s output which, despite his importance on the twentieth-century musical scene, remains largely obscure to this day. The style emerging from his days of writing music for Hollywood movies comes across as unashamedly romantic while surreptitiously collecting influences from Prokofiev, Stravinsky, Shostakovich, as well as much American music and jazz.

Although encompassing all these musical influences, the language of his later period nonetheless strikes me as utterly fresh and individual. And the works on our new album show a wide range of moods and style. His two Toccatas guilefully instill an American folk-like feel into Prokofievian irony and dynamism, his Carnival of the Beautiful Dresses appears as a wonderfully humorous nod towards Schumann’s Carnaval, and the Valentine Waltzes is surely one of the most intriguing sets of waltzes to emerge since Chopin.

The majority of the pieces in this volume are first recordings, and they include a few works that have never been published. Mother’s Day Piece, the first and earliest composition on the programme, has been kept in manuscript in the private collection of the Antheil Estate by Art McTighe, nephew of the composer. I am indebted to Mr McTighe for his generosity in granting me the privilege of introducing this intimate work, which was particularly close to the composer’s heart, to the listening public. In one of our exchanges, Mr McTighe kindly shared some rare photographs of a youthful George Antheil posing with his beloved parents. Pondering over the expressions of the Antheil family preserved in partially faded pictures, I felt the particular poignancy of undertaking the premiere of Mother’s Day Piece 79 years after its composition and of bringing to life these tender emotions from bygone times.

There are two more compositions in the recording which, through Mauro Piccinini’s guidance, I tracked down in manuscript form: the first version of the Presto from the Fifth Piano Sonata and the Waltzes from Volpone. These scores were neatly tucked away in the collection of Antheil’s papers at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts. Here, all documents had quite literally to be brought out through a set of double steel doors and heavy security. You can imagine the inward excitement I experienced in the restricted reading area of the Library when I first laid hands on these fragile manuscripts under the watchful eyes of the hawkish librarians. The dried ink on the half-century-old manuscripts seemed at odds with the stylish liveliness of their author’s handwriting. After this initial heart-fluttering in collecting all the scores, my appreciation towards these compositions deepened with each passing day spent at the piano, unravelling the vast and intricate musical landscape Antheil created within these works.

Mauro lent his guidance to help navigate me through the many unpublished works and subsequently brought his excellent narrative skills towards the intriguing article in the booklet. The recording sessions took place in the Sean Swinney recording studio in mid-town Manhattan, New York. My husband, Oliver Markson, who is a composer and pianist, worked with tireless dedication as co-editor in the post-production phase of the recording. (More information on his work can be found at his website.)

This first volume of recordings of George Antheil’s late piano works was released this month, August 2018. And we intend to return for another album of unfamiliar Antheil – watch this space.