For better or worse, I have always been highly (some would say provocatively) inquisitive, and not always content to accept, without question, received narratives of western music-history. Many years ago, as a music undergraduate, I spent countless hours in the library voraciously taking in anything and everything which challenged the boundaries of my knowledge.

Listeners might not know that there are vast collections of music known affectionately to us in the trade by such acronyms as ‘the DTÖ’ or ‘the DTB’ (‘Denkmäler der Tonkunst in Österreich’ and ‘Denkmäler der Tonkunst in Bayern’ – ‘Monuments of Music in Austria’ and ‘Bavaria’, since you ask), etc., full of works by composers nobody had ever heard of and painstakingly transcribed by leading scholars from original sources. Back in the 1980s and early ’90s they represented, to me, a tantalising labyrinth through which I felt I had to pass in order to set the lives, careers and compositions of the more famous composers in context.

Thirty years on, many of the composers in these Monumentae Musicae are, it is pleasing to report, reasonably well represented in recordings and on concert platforms. Meanwhile, new generations of scholars continue to unearth unsuspected music manuscripts, revealing repertory which does not always fit easily into mainstream music historiography and sometimes even prompts a rethinking of accepted paradigms.

Leading musicologists are often heard to stress the importance that scholars should not write about manuscripts without having analysed them properly, ‘in the flesh’. And yet time and again one encounter generalisations (sometimes repeated verbatim in secondary sources) about musical repertories, styles and personalities – generalisations which sometimes have to be challenged.

The interior of San Lorenzo in Damaso — where Sebastiano Bolis was maestro di cappella – in Rome (photograph courtesy of Maurice Whitehead)

Sacred music in late-eighteenth-century Rome, in particular, is an area ripe for exploration, partly because it has largely been written off by mainstream musicology as peripheral to more apparently modern and innovative developments elsewhere, and because no definitive, all-encompassing, study has yet been published. The impression gained from many music textbooks which do deal, fleetingly, with Rome during this period is of a city quietly decaying, overburdened by the weight of its ancient heritage, full of composers slavishly imitating the Palestrina style in order to satisfy the demands of Papal conservatism.

This apparent conservatism may well have been the case in the Sistine Chapel, St Peter’s Basilica and, to a lesser extent, in the three other Papal basilicas of San Giovanni in Laterano, Santa Maria Maggiore and San Paolo Fuori Le Mura. The initial fruits of my research have revealed that, just as had been the case in earlier times under prominent cardinals such as Ottoboni and Ruspoli (patrons of Corelli and Handel, respectively), many late-eighteenth-century Roman parish churches enjoyed the patronage of powerful ecclesiastical figures, sponsoring performances of sacred music which was anything but conservative.

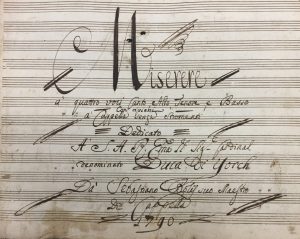

My interest in Roman sacred music of the eighteenth century had for many years been confined to composers active before 1760, such as Alessandro and Domenico Scarlatti, Pietro Paolo Bencini and Giuseppe Pitoni. The second half of the century had never been a major concern until 2011, when I started looking at music manuscripts in the vast Santini collection in Münster. I was intrigued to come across the dedication page of a Mass setting with its composer, Sebastiano Bolis, described as maestro di cappella, at San Lorenzo in Damaso, to Cardinal Henry Benedict Stuart, the grandson of King James II of England, brother of Bonnie Prince Charlie and last in the direct line of Jacobite succession.

Cardinal Henry, whose artistic patronage has been documented in books on eighteenth-century painting, sculpture and poetry, was well known to me through my work on the cultural life of the British Catholic community at home and abroad, but I was hitherto unaware of his musical patronage after he was made a Cardinal in 1747 by Pope Benedict XIV. It was a subject entirely untouched by modern scholarship.

One thing naturally led to another. I found several Bolis works in the Santini collection carrying the same dedicatory descriptions, and further searches revealed works by Bolis in the catalogues of various Roman parish church archives, and, significantly, in at least one British source.

My first task was to transcribe as much of this music as I could, partly as a way of fully understanding the style of a composer who is entirely new to modern English-speaking musicology (and, as far as Italian musicologists are concerned, known, by name, to only a few), but also as a way of setting it in the context of its time and place.

I also decided it was now time to dive, head first, into the vast 40-volume ecclesiastical diary kept by Cardinal Henry’s secretary, Giovanni Landò, held by the British Library, a source which has been largely avoided by scholars of Jacobite history, perhaps because one of its nineteenth-century detractors, James Dennistoun, described it as a ‘heap of puerile prolixity’!

Not only does the Landò diary reveal much about the involvement of Bolis in the provision of sacred music for Cardinal Henry, but it also confirms his role as maestro di cappella at two of the principal venues for Henry’s patronage of sacred music, the church of San Lorenzo in Damaso (within Henry’s residence, as Vice-Chancellor of the Roman Church (from 1763) at the Palazzo Cancelleria), and the Cathedral at Frascati, where Henry had been Bishop since 1761.

One of the earliest engraved images of Henry Benedict Stuart, shortly after becoming a Cardinal – at the age of 22

The Landò diary also contains references to music which Bolis provided for Carnival and Lent at Frascati, as well as the names of many other composers directly or indirectly associated with Cardinal Henry. From 1778 (the year in which Bolis succeeded Giovanni Battista Costanzi as maestro di cappella), onwards, Bolis provided new sacred works for San Lorenzo on a regular basis, one of the most important occasions being the Patronal Feast, 10 August.

Having dusted off centuries of obscurity and neglect, it soon became apparent to me that, through the music of Bolis and his contemporaries, I was revealing two forgotten phenomena, the fabulous music of a Roman composer who deserved recognition, and the musical patronage of a cardinal who had long been resolutely denounced by Whig historians as a pompous irrelevancy.

The music of Bolis and his contemporaries, as well as the patronage of Henry Benedict, should be of interest to anyone with a passion for the Rome of Johann Winckelmann and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, of Pompeo Batoni and Charles Burney, the Rome that was a magnificent melting pot of artists, writers and musicians – indeed, the Rome of the Grand Tour.

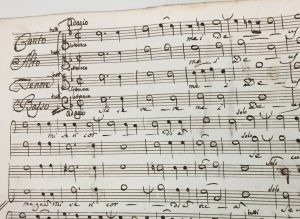

In 2014 and 2015 Cappella Fede, a specialist period ensemble I founded in 2008, undertook the first modern performances of several sacred works by Bolis, revealing the striking depth and breadth of his musical palette, ranging from penitential a cappella psalm settings to fully orchestrated Mass and Vespers settings. Depending on the liturgical season or appropriate feast, Bolis can be lively and effervescent, or dark and sombre. Audience reactions to Bolis’ music were tremendous, as was the encouragement to record the music as soon as possible.

With the support of Oscott College, Birmingham, Cappella Fede recorded works by Bolis and other musicians in Cardinal Henry’s circle in the summer of 2015. Thanks to the fantastic support of the enterprising and daring Martin Anderson and his Toccata Classics label, we can now gain a tantalising glimpse into the still largely unknown yet evidently vibrant sound world of sacred music in late eighteenth-century Rome. It is only the tip of what may well prove to be a very large iceberg.