Ever since, some years ago, I heard the State Philharmonic Orchestra of Rhineland-Palatinate performing a symphony by Friedrich Gernsheim (1839–1916), I have been seeking to promote his music through my own efforts as a pianist.

Restoring the scores from the autograph manuscripts, practising his music, performing and recording it has led to an intense engagement with this forgotten musician, friend of a Who’s Who of German composers in the second half of the nineteenth century – Brahms, Bruch, von Bülow, Mahler and more.

When I first started to look for Gernheim’s piano music, not much was available. Then I found out that the National Library of Israel hosts the Gernsheim archive and I was able to obtain digital copies of the autographs of the three early piano sonatas. The process of restoring the music was quite an undertaking: Having been about fifteen years old at that time, Gernsheim composed these large-scale piano pieces in an enormously short period under the auspices and guidance of Julius Rietz, his composition teacher at the Leipzig Conservatoire. Sometimes the young man’s corrections overgrow the original text and lead to a musicological puzzle that requires disentanglement.

The music I discovered and the critical welcome given the first album of Gernsheim’s piano music (Toccata Classics TOCC 0206) in 2019 was so encouraging that I happily accepted Martin Anderson’s suggestion that I record Gernsheim’s complete output for piano, and so I started to select a programme for the second album. Then the corona pandemic struck, and my concert schedule came to a sudden halt. That gave me more time to turn the pieces inside out and back again before the recording session, but also allowed the possibility of obtaining a grant from the Cultural Foundation of the Federal State of Hessen (the Hessische Kulturstiftung) for a ‘sustainable’ musical project, which I used to record the second volume, now released.

The year 2021 marks the celebration of ‘1700 Years of Jewish Life in Germany’. In the dark years of German history from 1933 to 1945, Gernsheim’s music was banned from performance. Karl Holl’s invaluable biography, Friedrich Gernsheim: Leben, Erscheinung und Werk, written in consultation with Gernsheim himself, was published in 1928 by Breitkopf & Härtel – and it was one of the books burned by the Nazis on 10 May 1933. If bringing Gernsheim’s music to life were not joy enough, the opportunity to contribute to this year of 1700 Years of Jewish Life in Germany is an honour in itself.

And there was another pleasure involved in the making of the second album. I wanted to involve a young audience in the discovery of Gernsheim’s piano music – the grant I was awarded was, after, for a ‘sustainable’ music project, and the future of music in general, and Gernsheim’s in particular, can be sustained only if younger generations feel themselves personally engaged in it somehow. My suggestion fell on fruitful ground in the city of Worms, Gernsheim’s home-town. The city is known for the Diet of Worms in 1521, and the prescription of Martin Luther which followed, but it was also one of the central cities of Jewish culture and life in the Middle Ages, aside from Mainz and Speyer.

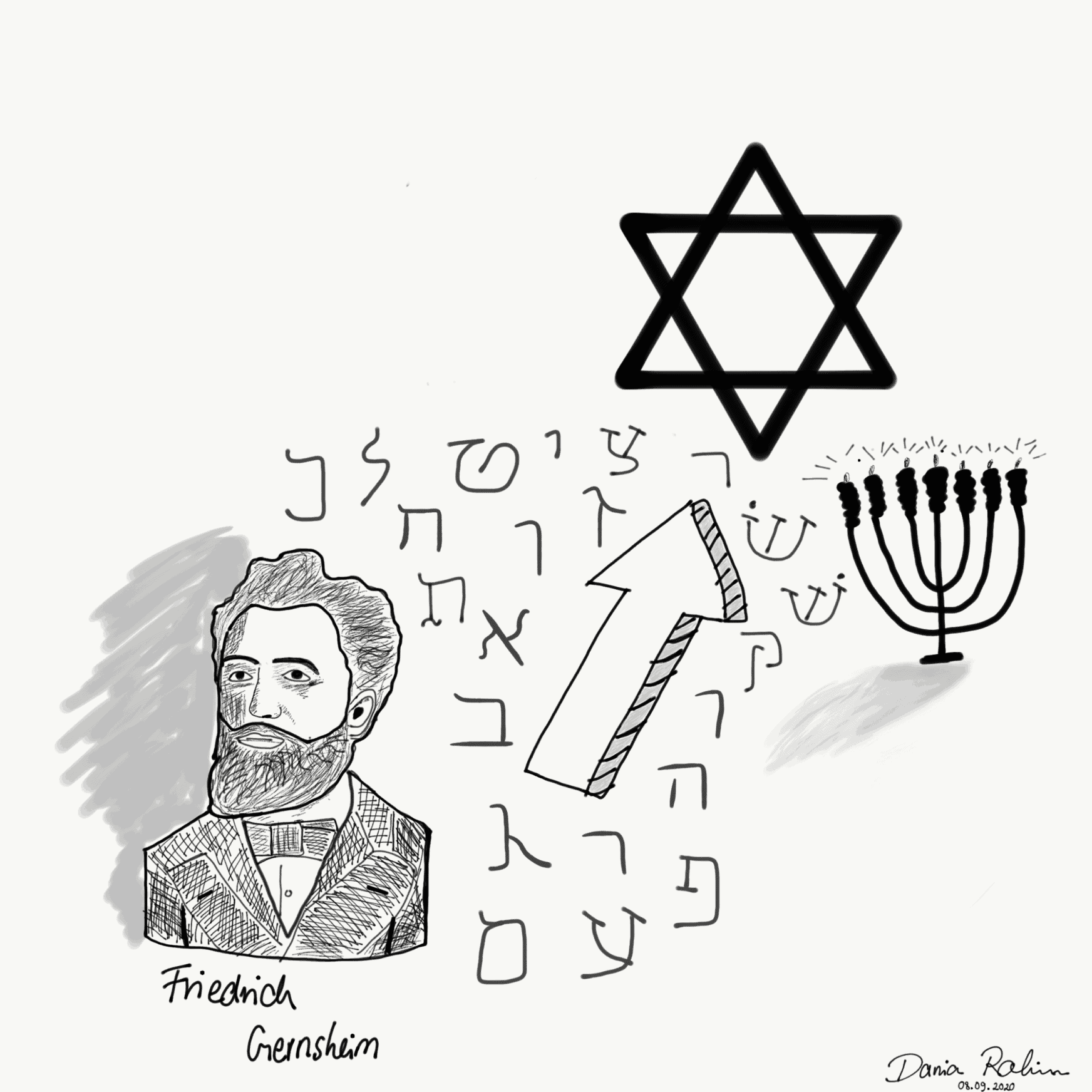

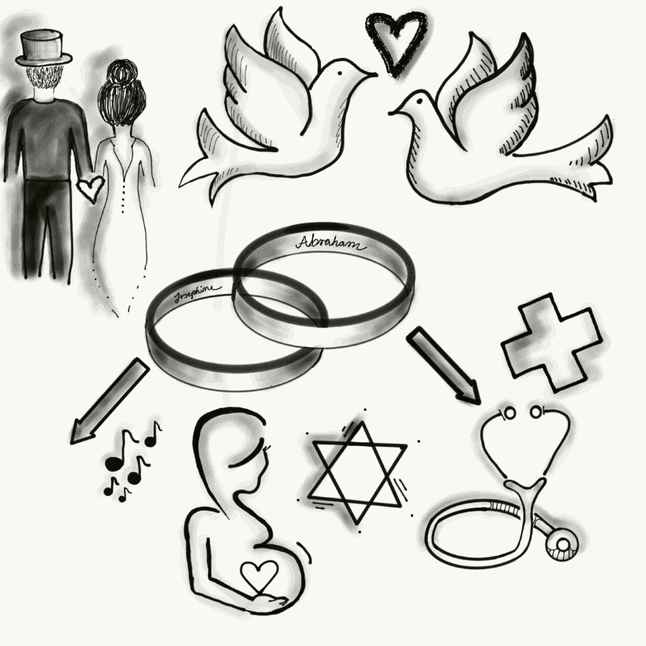

Victoria Selbert, a singer and music-critic in Worms, introduced me to Dr Markus Wallenborn, director of the prestigious Rudi Stephan-Gymnasium in Worms (Stephan is another forgotten composer who deserves attention). He, together with the art teachers Katharina Traut and Reinhard Tiemann, immediately embraced the idea of getting young people involved, so that I was able to give a workshop at the school. After my introductory lecture on Gernsheim’s life and work, the students started to draw ‘sketch notes’ as I played some of the newly discovered piano music — as a technique to consolidate points heard in a lecture, with rather simple, quickly made pictures intended to make the content of the lecture more easily recalled.

Within a month, the students had created an impressive body of images, some of which went into the booklet. In view of its limitations of space, a first selection of the drawings was made. This blog allows me, though, to reproduce them all, preceded by an outline of the event in Gernheim’s life that they illustrate:

The Gernsheim family came to Germany with the major wave of emigration of Sephardic Jews expelled from Spain in the fifteenth century.

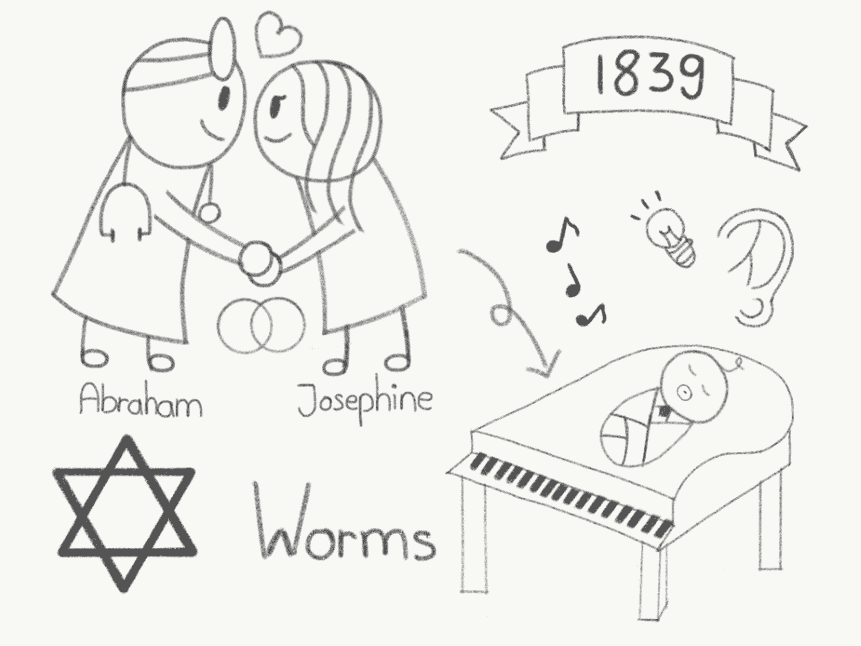

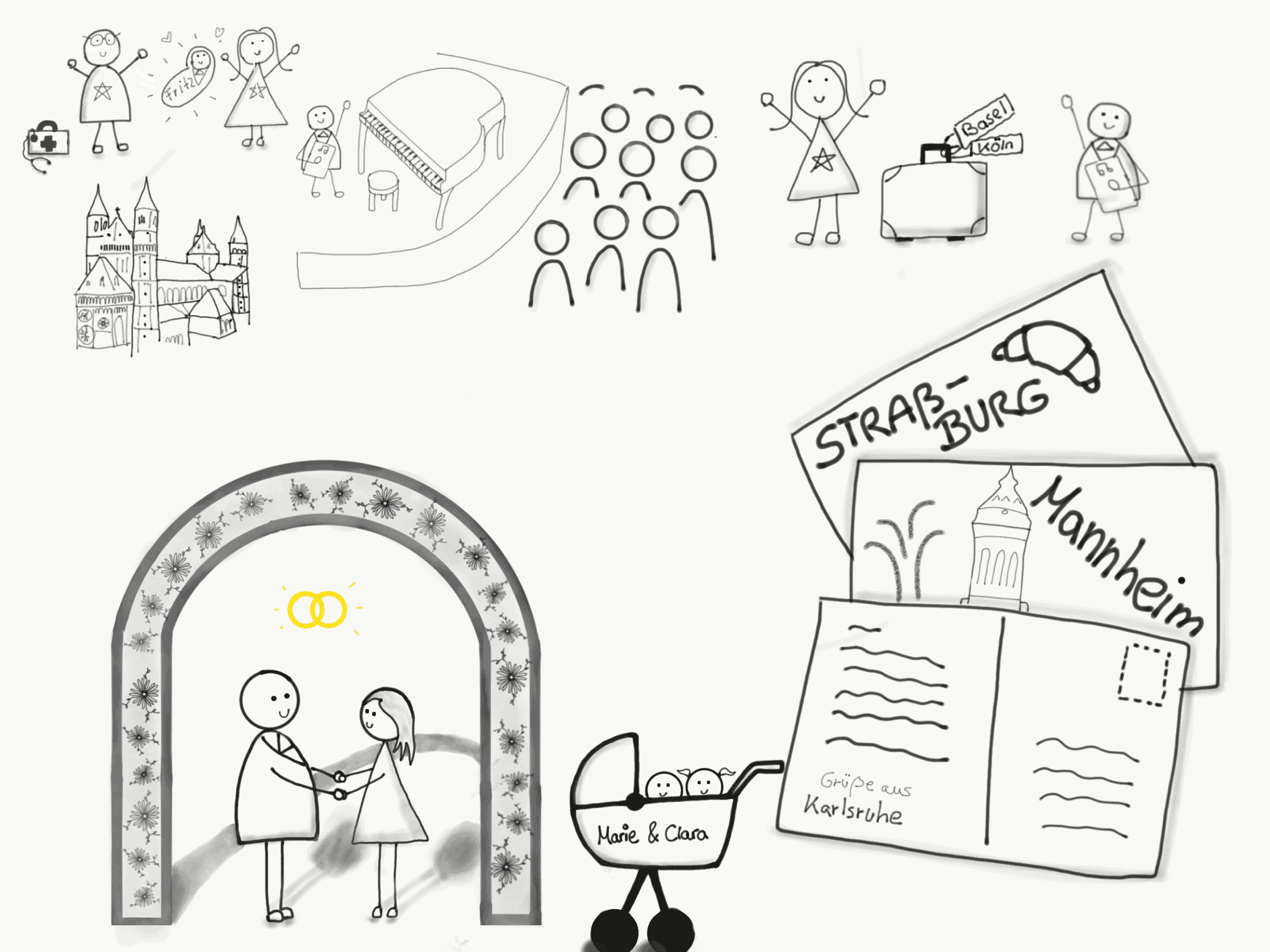

Abraham Gernsheim (1801–71) married Josephine, née Kaula (c. 1806–89). Their only son was Friedrich (1839–1916). Father Abraham was a doctor in Worms, the mother a fine amateur pianist.

The family tree: Josephine Kaula, who played the piano and Abraham Gernsheim, medical doctor from Worms, both from Jewish families, got married. They named their son Friedrich, but called the young boy ‘Fritz’. Josephine was to give her son his first piano lessons.

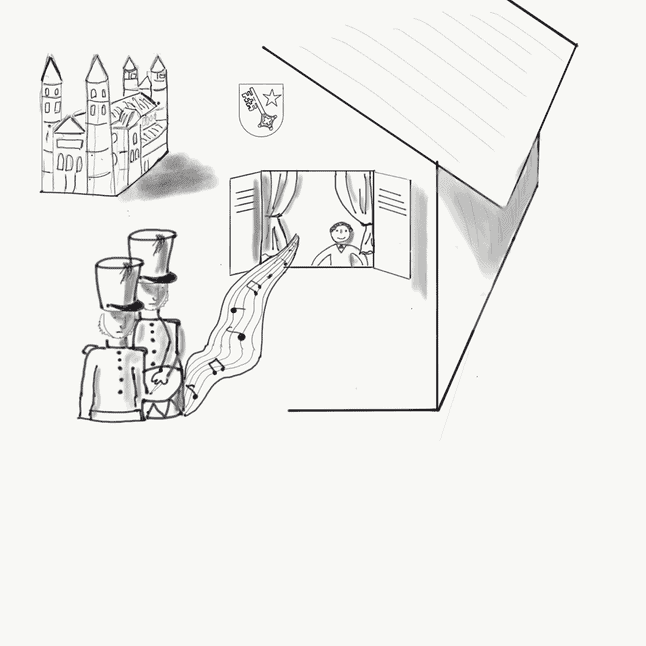

Early years: through the windows of their house, six year old Fritz listened to a passing military band, playing a march in the streets of Worms, and wrote down the music by ear.

Doctor Abraham (Gernsheim) married the amateur pianist Josephine (Kaula), both from Jewish families. Abraham, who also played the flute, would play chamber music with Josephine on the piano whenever their time allowed it. Music was implanted into the young child from the beginning of his life. The parents discovered that the boy had an extraordinary ear: he could sing and play tunes on the piano by ear.

Fritz, who was home-schooled by his mother, played the piano and violin and composed. He would sit for hours at the piano, playing and experimenting with the sounds he produced. He was considered a wunderkind.

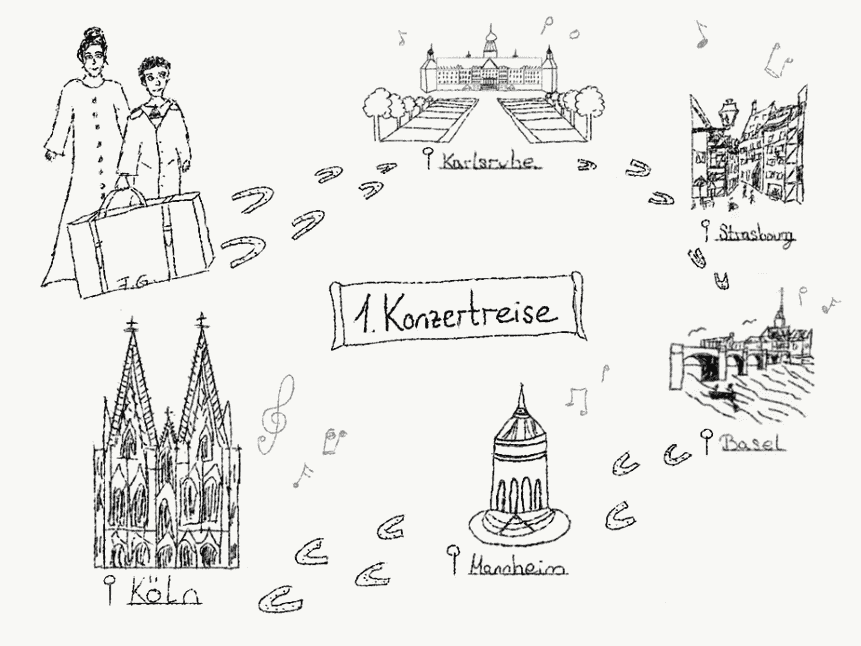

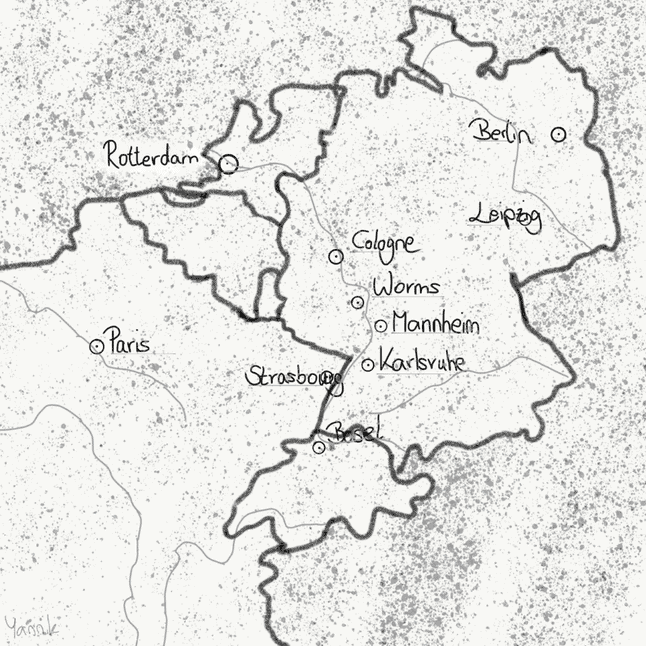

Because of the turmoil in the days of the German revolution (1848–49), for safety reasons Abraham Gernsheim sent his wife and child first to the city of Mainz and then on to Frankfurt, where the child could get a better education. At the age of twelve to thirteen, young Friedrich was ready for his first concert tour. Together with his mother, he went to Mannheim, Karlsruhe, Strasbourg, Basel, and Cologne (Köln).

A map of Germany and the bordering countries following the concert tour of the young Gernsheim shows the outreach of his early fame.

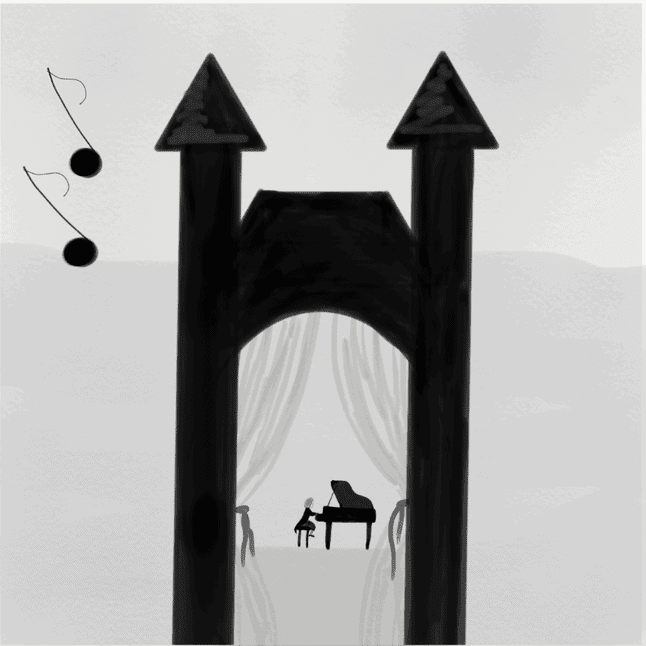

After his first concert tour, he entered the Leipzig Conservatoire. Established in 1843, the Leipzig Conservatoire (today the University of Music) is the oldest musical academy in Germany. One of the founding members was Felix Mendelssohn (1809–47). Gernsheim, who passed his exams with the best results and highest acclaim, trained and judged by such renowned musicians as the virtuoso pianist Ignaz Moscheles, the composer Julius Rietz and Ernst Friedrich Richter, one of the successors of J. S. Bach in the post of Cantor at the Thomas-Kirche in Leipzig.

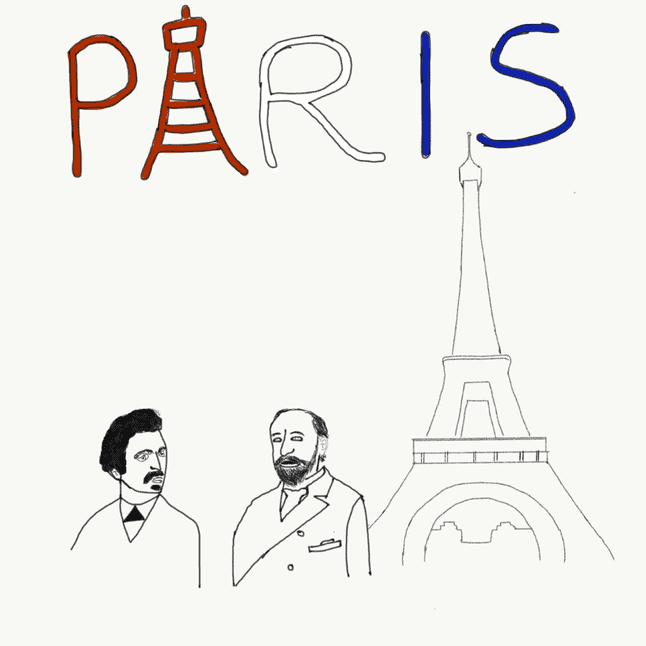

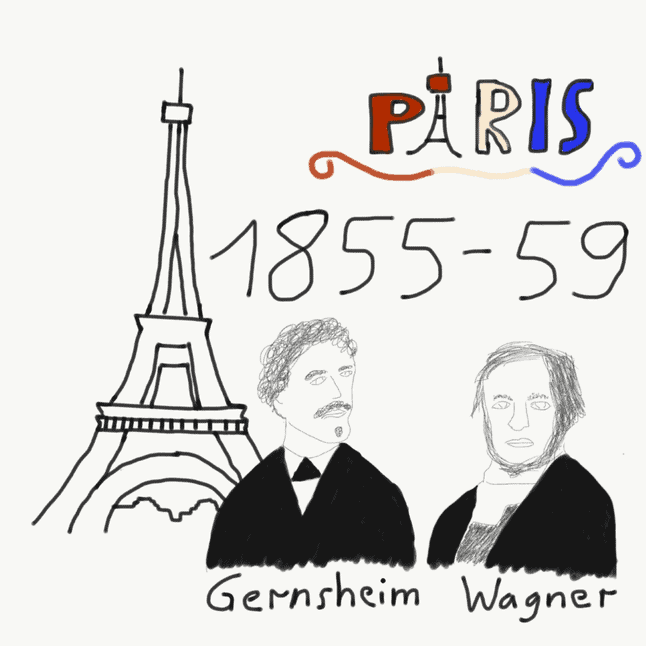

After his studies in Leipzig, Friedrich moved to Paris, the centre of the musical world of Europe in those days. Gernsheim’s parents wanted their son to enjoy what Holl in his biography called the ‘benedictions of Paris’ (p. 28), and they accompanied Friedrich to the city of lights, arranging a concert tour on the way to Strasbourg, Mulhouse and Nancy before they arrived in Paris. A friend of the family, an engineer officer by the name of Théodore Parmentier, himself a musical journalist and patron of the arts, helped connect the family with some of the major names of musicians who lived in or passed through Paris at that time, people like Camille Saint-Saëns, Frédéric Chopin and Hermann Levi, from whom Gersheim later ‘inherited’ the post as musical director in Saarbrücken in 1861.

The singer Julius Stockhausen, too, who also introduced Friedrich to the highest circles of Parisian society, helped the young man establish his name in the French capital. Gernsheim met Wagner and witnessed the Tannhäuser scandal in 1861 himself. In Paris, too, Gernsheim befriended Rossini, who dedicated a little piece to him, and in whose house he met and heard Liszt and Anton Rubinstein.

Gernsheim stayed for five years in Paris, which for the young musician was the ‘high school of life and art, full of passion and grief’, as Holl put it (p. 39). His first position after those years of studies was in the city of Saarbrücken, on the French border. He was appointed director of the choral society, a humble post for an aspiring conductor and composer of Gernsheim’s ability. But in the house of the family Gouvy, he found new friends and a spiritual home – Théodore Gouvy was a composer himself. Henriette Gouvy, the well-connected lady of the house, became Gernsheim’s student, and to her he dedicated the Preludes, Op. 2, heard on Volume One of his piano music.

From Saarbrücken, he had travelled for concerts, meeting Brahms in Cologne in 1862 at the house of their mutual friend, the composer Ferdinand Hiller. Cologne became a centre of attraction for Gernsheim and, when a position at the Conservatoire there opened in 1865, Gernsheim applied. With letters of recommendation letters from Hiller, he obtained a teaching post and also became director of the city choral society and musical society. His most famous student from that time was Engelbert Humperdinck, later the composer of Hänsel und Gretel.

In 1874, Gernsheim moved again, this time to Rotterdam, which then had the only German-speaking opera house in the Netherlands. Gernsheim was offered the position as director of the Maatschappiy tot bevordering van toonkunst (‘Society for the Advancement of Musical Art’), which required him to conduct big choral and orchestral concerts as well as teach at the conservatoire. It was in Rotterdam that – at last financially secure – he decided to marry a friend of his youth: Helene Hernsheim from Karlsruhe. They had two daughters: Marie (who died in a car accident in 1915) and Clara.

In 1890, Gernsheim applied for a position in Berlin at the Stern Conservatoire. The administration had already asked Gernsheim ten years earlier, but could only offer the position as a choir director without an orchestra, and so Gernsheim declined the job offer. But now, in 1890, he agreed since he was able to conduct not only the choir but also a newly founded orchestra. Very soon, critics and public alike praised the discipline, clarity, tone and the lively and warm sound of the choir.

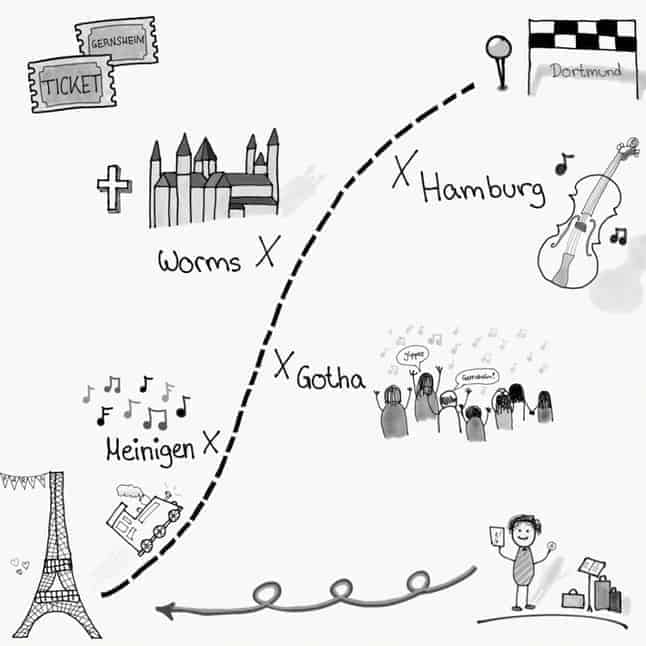

During his time in Berlin, Gernsheim was able to tour again as a pianist and conductor. Not only did he return to Worms twice to perform, but also went to Paris, Meiningen, Gotha and Hamburg (for the premiere of his Second Violin Cncerto). In 1914, Georg Hüttner, first conductor of the Dortmund orchestral society, organised a two-day festival dedicated entirely to Gernsheim’s music, with the composer present.

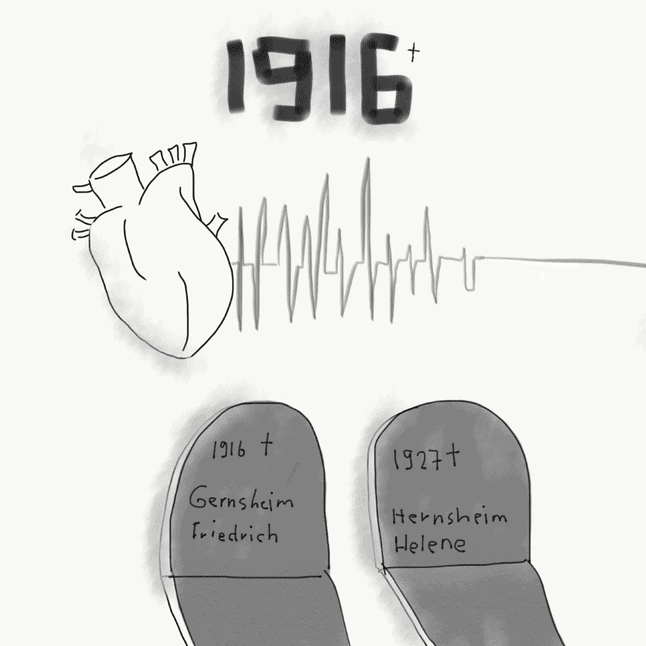

Gernsheim was equipped with excellent physical health throughout his life. In the spring of 1916, however, he had bladder trouble and went on a health cure for five weeks in a Berlin clinic and, later, in Bad Wildungen, in Hesse, in central Germany. However, his stay in Bad Wildungen was cut short because of severe heart problems, and in the night of 10–11 September 1916, Gernsheim died. He is buried in the famous Weissensee cemetery in Berlin. His wife, Helene, followed him eleven years later.

Students of the Music University (Hochschule für Musik), members of the Ministry of Education and Culture and members of the Academy of Arts in Berlin held a wake in Gernsheim’s honour, Holl writing (p. 89) that ‘the memorial, more lasting than stone and ore, was already erected by the master himself during his lifetime: in the hearts of his students who propagated the teaching, in the annals of contemporary musical history and in the best of his works’.

Friedrich Gernsheim’s music is well worth (re)discovery. Facile assessments – such as ‘He sounds like Mendelssohn’ or ‘He shows influences of Beethoven or Schumann’ – fall short of the experience of listening to the unique voice of this composer. As he said to his composer friend Ferdinand Hiller, ‘One does one’s best, represents musical Germany to the outside world and in a not bad way, and then the very wise gentlemen come and say “he is a Jew” or, which borders on bigotry, “he has too many Jewish followers, he does not belong to us”’.1

I am grateful to Martin Anderson, Seth Blacklock, Volker Gallé, Dr David Maier, William Melton, Viktoria Selbert, Reinhard Tiemann, Katharina Traut, Dr Markus Wallenborn, the Kulturstiftung Hessen and, of course, to all the creative, wonderful young pupils of the Rudi Stephan-Gymnasium in Worms.

- Quoted in Doris Kösterke, ‘Jens Barnieck erinnert an Gernsheim’, Frankfurt Allegemeine Zeitung, 18 June 2020.