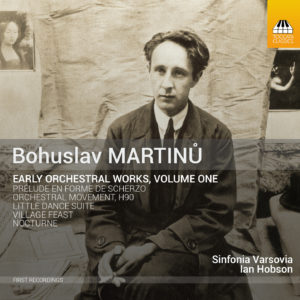

The publication of Martinů and the Symphony in 2010 brought a few unexpected opportunities my way. Even before the book appeared, I had taken part in a Martinů conference in Prague and a BBC study day on his symphonies in the Barbican Centre in London. I also did a couple of pre-concert talks for the BBC and wrote booklet notes for several CD releases (most notably, Jiří Bělohlávek’s award-winning set of the Martinů Symphonies). But a more intensive re-engagement with Martinů’s music seemed unlikely. Then, in November 2011, Martin Anderson e-mailed me with the following information: ‘When Ian Hobson was last in town, I gave him a copy of your book, with the suggestion that the early Martinů orchestral works that you detail would make an important recording project’.

Ian Hobson, winner of the Leeds International Piano Competition in 1981, had already appeared on Toccata CDs in music by Ernst, Enescu and others, but was keen to enlarge his discography with an interesting and substantial project for him as conductor. He already had an association with Sinfonia Varsovia, an orchestra that had recently accompanied cellist Sonia Wieder-Atherton on CD in an arrangement of Martinů’s ‘Slovak Variations’. I was more than keen to be involved in this new venture.

The first step was to ‘scope’ the project. Halbreich’s catalogue of Martinů’s works lists over 130 items written before the composer’s departure for Paris in 1923. The vast majority are piano pieces and songs (now easily available thanks to the supreme efforts of Giorgio Koukl and Jana Wallingerová). The orchestral works are far less numerous, but still enough to make the project a substantial one; seven single-movement works (Village Feast, The Death of Tintagiles, The Angel of Death, an untitled piece (H90 in Halbreich’s catalogue), Nocturne, Ballad (Villa by the Sea) and Dream of the Past, two orchestral cycles (Little Dance Suite and Vanishing Midnight) and three ballets (Night and The Shadow in one act, Istar in three).

Only one of these works had been recorded in its entirety; Dream of the Past appeared on a Panton LP which is now extremely difficult to find. The two suites from Istar had been issued (with some cuts) on Supraphon, but these recordings are likewise hard to obtain nowadays. I also had non-commercial recordings of Nocturne and Ballad. These pieces were broadcast on Brno Radio in 1963, as was the Little Dance Suite, though the latter performance does not appear to have been preserved. Published material was also scant; the Istar suites and Dream of the Past had been available for some time and Sandra Bergmannová, formerly of the Martinů Institute, had recently worked with Baerenreiter Praha on scores and parts for Nocturne and Ballad. Everything else would require the preparation of performance materials, and this was to be my task.We originally felt that we could simply go ahead unencumbered by considerations of copyright. Halbreich’s revised catalogue, issued in 2007, stated that the publishing rights for all these works were still free. However, it transpired that the rights had subsequently been acquired by Baerenreiter Praha and Schott. This information had a bearing on the programming of the first album. If it were to contain works from both publishers, we would need to negotiate with both, potentially causing a delay. The first album was therefore largely limited to works from Baerenreiter, who allowed me to prepare materials for Posvícení, Little Dance Suite and H90. In spite of this initial restriction, the CD proved to be varied and engaging. Every early influence on Martinů is represented here – his fascination with Impressionism is made clear by Nocturne and H90. Harmonies redolent of Richard Strauss still cling to the opening Waltz of the Little Dance Suite, whereas the remaining movements pay fuller tribute to Martinů’s great Czech predecessors Dvořák (Song and Scherzo) and Smetana (the Polka finale). The album therefore encapsulates the entire series; it has proven to be a popular release. I hope that the following account of it will interest readers who have already bought a copy and intrigue those who have not.

£8.00 – £12.50Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

We opened the album with a slight cheat – a tiny work which had been published by Leduc but never recorded. In 1929 Martinů wrote a set of eight piano preludes and later orchestrated one of them. Although this Prélude en forme de scherzo was outside the period we had elected to cover, we decided to take pity on it. It was unlikely that anyone else would ever record it and, besides, a piece entitled Prélude seemed the ideal way to launch the album and the whole series. It’s a boisterous little number, somewhat dissonant and spiky, whose rhythms distinctly anticipate the scherzo of the First Symphony.

The second item on the disc is an orchestral movement which is rather mysterious – not only in the nature of its material, but in its origins. The title page is missing, so we have no idea what it is called. The first surviving page bears no tempo indication, and the work was designated a fragment in Halbreich’s catalogue (it has the number H90, and that’s what I usually call it). Ian’s performance proves that the movement is complete, and brings out the clear debts to Debussy (whose faun is evoked by the indolent cor anglais solo) and Ravel (a four-note ostinato redolent of the Rhapsodie espagnole dominates the outer sections). The alluring combination of harp, piano and celeste adds glitter and zest to the scoring, enhancing the somewhat oriental atmosphere. It’s an attractive work, as someone at the BBC clearly realised; it featured in the Radio 3 series Words and Music, in an episode entitled Below the Surface.

- Prélude en forme de scherzo, H181a (1929, orch. 1930)

- Orchestral movement, H90 (1913–14)

- Posvícení (‘Village Feast’), H2 (1907)

- Nocturno 1, H91 (1914–15)

- I Tempo di valse

- II Moderato: Píseň (‘Song’)

- III Scherzo

- IV Allegro à la polka

Little Dance Suite, H123 (1919)

Posvícení (loosely translated as ‘Village Feast’) is, as far as we know, Martinů’s second completed composition, following his string quartet The Three Riders after a gap of five years or so. Whether it is really an orchestral piece is debatable – but it certainly sounds well as presented in this album. The work is for flute and seven-part strings (with three violin and two cello parts in addition to viola and bass). In the first edition of his catalogue, Halbreich describes Posvícení as a piece for flute and string orchestra, but by the revised edition he had changed his mind and regards it now as Martinů’s only octet. Perhaps that is the case. The work is based on a traditional Czech song, the first appearance of which is delivered by two cellos and a viola, all marked ‘solo’. This marking might indicate that massed strings are intended – but it’s not conclusive proof. Composers sometimes use the word ‘solo’ to tell a performer that he is temporarily in the spotlight. Whatever the truth may be, the rhythmic vigour and sonic bite of orchestral strings in the final dance undoubtedly turn the humble Posvícení into one of the highlights of the album.

The following Nocturne is a much more subdued work, dating from around 1912. In Halbreich’s catalogue, it immediately follows H90 but is far more shadowy and withdrawn. Long solos for viola and violin open and close the work, with a brief and more passionate outburst for the full orchestra occupying the central phase. In the Martinů conference at Prague that I mentioned above, I heard Sandra Bergmannová give an account of her work preparing this piece for publication. She mentioned a number of problems which exist in Martinů’s early manuscripts, including:

- Note-lengths that make no sense in the context of the bar

- Parts for one instrument accidentally notated on the staff of another

- Problems when writing for transposing instruments

- Completely blank bars in instruments at points where they should clearly still be playing.

I was to encounter all these problems and more when working on the Little Dance Suite, the concluding and principal work on the first album. It was written in 1919, and intended for performance by the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra the following year. Václav Talich withdrew the work at the rehearsal stage for reasons which are not entirely clear, but could the state of the manuscript and the orchestral parts be among them? I have examined the original orchestral parts at the Martinů Centre at Polička and can confirm that its myriad errors have been faithfully copied into the parts. I find no fault with the copyist, who could not be expected to be editor and proof-reader as well. This was not the first time Martinů had submitted a work for performance in such a poor state of readiness, and I find it difficult to understand how he could be quite so negligent. I certainly have no idea how the Brno radio performance of the Little Dance Suite surmounted these difficulties.

I had long been convinced that the Little Dance Suite had real merit and enormous charm, and that it would justify the many hours required to puzzle out Martinů’s real intentions. The material was only just ready in time for the recording sessions before Christmas 2012, but the results not only vindicated our faith in the work, but also proved that, in Ian Hobson, we had found a most persuasive advocate for this music. It’s been a privilege to work with Ian. I often feel I have no business advising someone who has achieved as much as he has – but it’s a feeling which arises from my own insecurity, in spite of the fact that he has twice travelled to Ebbw Vale to discuss the project with me. Ian has sometimes over-ruled me, and has invariably been proven right to do so. More often, he has taken my advice on board but then completely transcended it, producing performances with Sinfonia Varsovia which far outshine anything I could have imagined. The finale of the Little Dance Suite is an excellent example. It sets off with a kaleidoscopic succession of disparate ideas, flirts only briefly with polka rhythms (despite having the title A la polka) and finally alights upon a magnificent theme in B major. I had severe doubts whether this potentially chaotic jumble could be delivered with any sense of coherence, but Ian and the orchestra knew exactly what to do with it, fashioning from it an uplifting and euphoric conclusion to the programme. The whole album is admirably summed up by the following sentence, taken from an online review by Brian Reinhart: ‘It made me happy – it’s an hour of sheer aural satisfaction, and it’s downright bizarre that this music isn’t better-known. Treat yourself!’

Although Volume One in our series consisted entirely of first recordings, all of the pieces except H90 had been performed at least once (if we include solo piano performances of the Prélude). Volume Two is a complete contrast, featuring a single work, not one note of which has previously appeared before the public. The work in question is the hour-long ballet Stín (‘The Shadow’), completed at Christmas 1916. In the next part of this blog, I shall give you some insight into just how difficult it proved to drag this obscure and recalcitrant score into the light.

It is very interesting to hear about the background to these lovely pieces. Just imagine an orchestral rehearsal for those pieces with multiple errors in the copies – no wonder the performances did not go ahead. Thank you all for finally bringing the works to life. They are fresh and vibrant, and I hope they sell well. In any event, Mike – you have definitely now found your vocation and finally grown up!