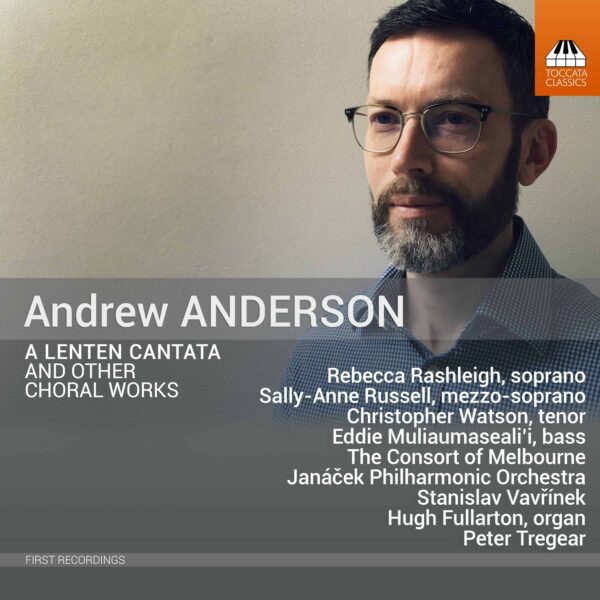

The longest piece on the new Toccata Classics album of my choral works is A Lenten Cantata. It was premiered in 2017 with organ and three-part string accompaniment, but in the recording it is the fully orchestrated version, completed in 2020, that can be heard. As explained in the booklet notes, it was commissioned by the Rev. Matthew Williams, who had long wanted to explore what a contemporary composer would create within the older form of a cantata. On reflection, I realise that the idea of using older musical forms and aesthetics within a more modern compositional idiom is something in which I have long been interested.

Neo-Classicism

In 1989, one of my high-school subjects in my final year was the somewhat prosaically named ‘Music B’. Music B was about music theory and history, in contrast to the music performance subject called ‘Music A’ (which I also took). I was the only student in my school to take Music B, which I suspect created headaches for the poor teacher charged with generating the timetable.

The periods I selected to study were Impressionism and Neo-Classicism, with the work I studied for Neo-Classicism being Stravinsky’s Symphony of Psalms. I was not familiar with this piece, but I quickly fell in love with it, listening to it repeatedly as I studied the score. Had the Rev. Williams asked the teenage me about what a modern composer would make of the old form of a cantata, I would no doubt have launched into an extended speech about Neo-Classicism. Marrying twentieth-century tonalities with the refined musical structures and aesthetics of the classical period was what the Neo-Classicists were all about.

When listening to Symphony of Psalms, I was particularly captivated by the fugal opening of the second movement. It struck me as simultaneously beautiful and impenetrably clever. I couldn’t imagine how someone could write such a thing, which seemed so far removed from my eighteenth-century harmony and counterpoint exercises (the other part of my Music B studies). I suspect that part of my love for contrapuntal textures stems from this encounter, and they feature in several works – for example, the second and fourth movements of my first Piano Quartet (2010), and the final movement, ‘Inquieto’, of my Piano Trio, The Heart (2013). The contrapuntal opening of the final (eighth) movement of A Lenten Cantata, ‘Plenteous grace with thee is found’, is a conscious nod to Symphony of Psalms. Indeed, the orchestration of the final voice in the opening fughetta – for flute, doubled at the octave by piccolo – was a deliberate evocation of Stravinsky’s voicing.

I think there is another similarity between my cantata and Symphony of Psalms.1 Stravinsky completely eschews upper strings (violins and violas) in his orchestration. Although violins and violas are included in A Lenten Cantata, in general they are used less than the woodwind, in contrast to conventional orchestral usage.2 Indeed, I think this is one of the reasons that – at least to my ear – the more conventional use of strings in the fifth movement brings with it a refreshing aural change. This change deliberately highlights the one lighter movement in the cantata, sung by solo soprano (‘Cast thy burden upon the Lord, and he will sustain thee’ – with a clear emphasis on the positive sentiments of casting and the sustaining, rather than on the negative burden). With a theme of Lent, some means needed to be found to prevent the cantata being an unbroken string of solemn movements!

Recording in the Time of Pandemic

© Janáček Philharmonic

As noted above, A Lenten Cantata is the longest work on the disc. It also calls for the largest forces. Making a recording involving around a hundred musicians – being recorded over multiple sessions and in separate parts of the planet (Ostrava, in the Czech Republic, and Melbourne, Australia) – presents several technical challenges. Attempting all this in 2021, while the world was dealing with a pandemic, might seem to border on foolhardy. Remarkably, we managed to dodge various disruptions – not an easy feat, given that Melbourne has the dubious honour of being the most locked-down city on earth – and brilliant audio engineer Mark Edwards applied his sensitive technical and musical skills to bring everything together. The project has involved the talents and hard work of many people, and so I hope you enjoy what we have created.

1 I am conscious that composers’ views on what has influenced their compositions may be quite different from the influences discerned by audience members: this is something I have reflected on recently in the programme notes for a concert of my chamber music: cf. www.andersoncomposer.com/fluorescence.

2 Kent Kennan and Donald Grantham, The Technique of Orchestration, sixth edition, Pearson Education, Inc., Cranbury, New Jersey, 2002. For example, Kennan and Grantham declare that the strings are the ‘backbone of the orchestra’, given that they are typically found to play the most, followed by the woodwind and then the brass.