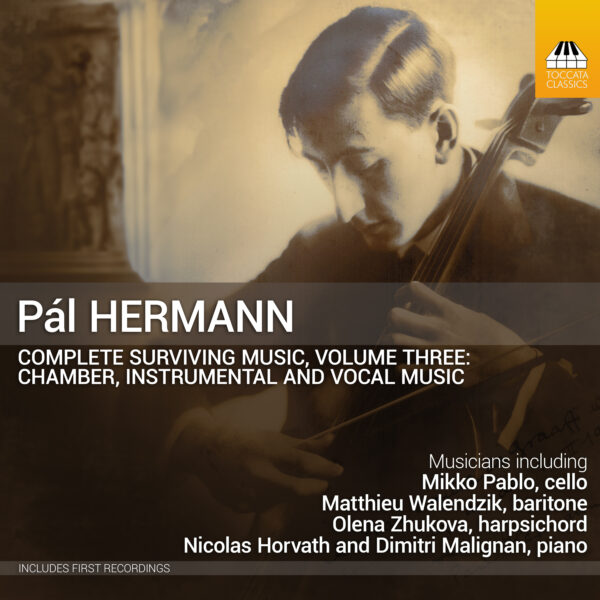

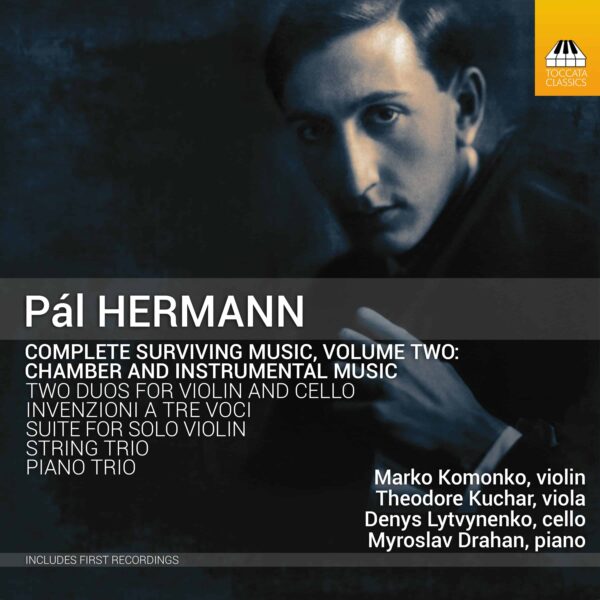

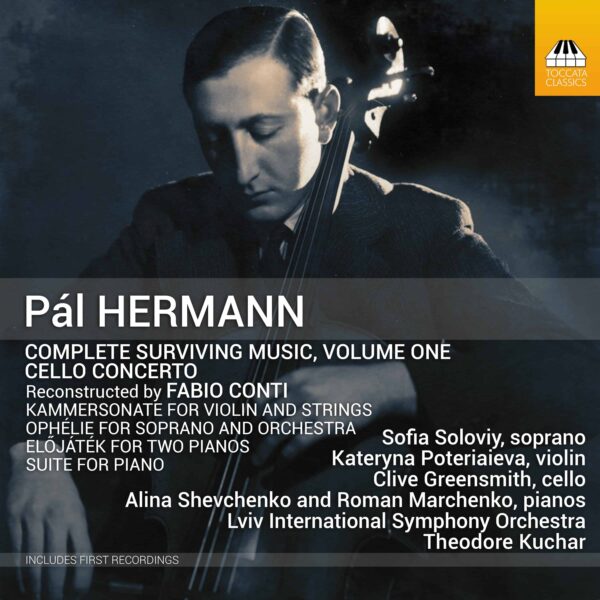

Corrie Hermann offers some touching and affirmative thoughts as a postscript to the third and final recording of the complete surviving works of her father, composer and cellist Pál Hermann, released by Toccata Classics in March 2024.

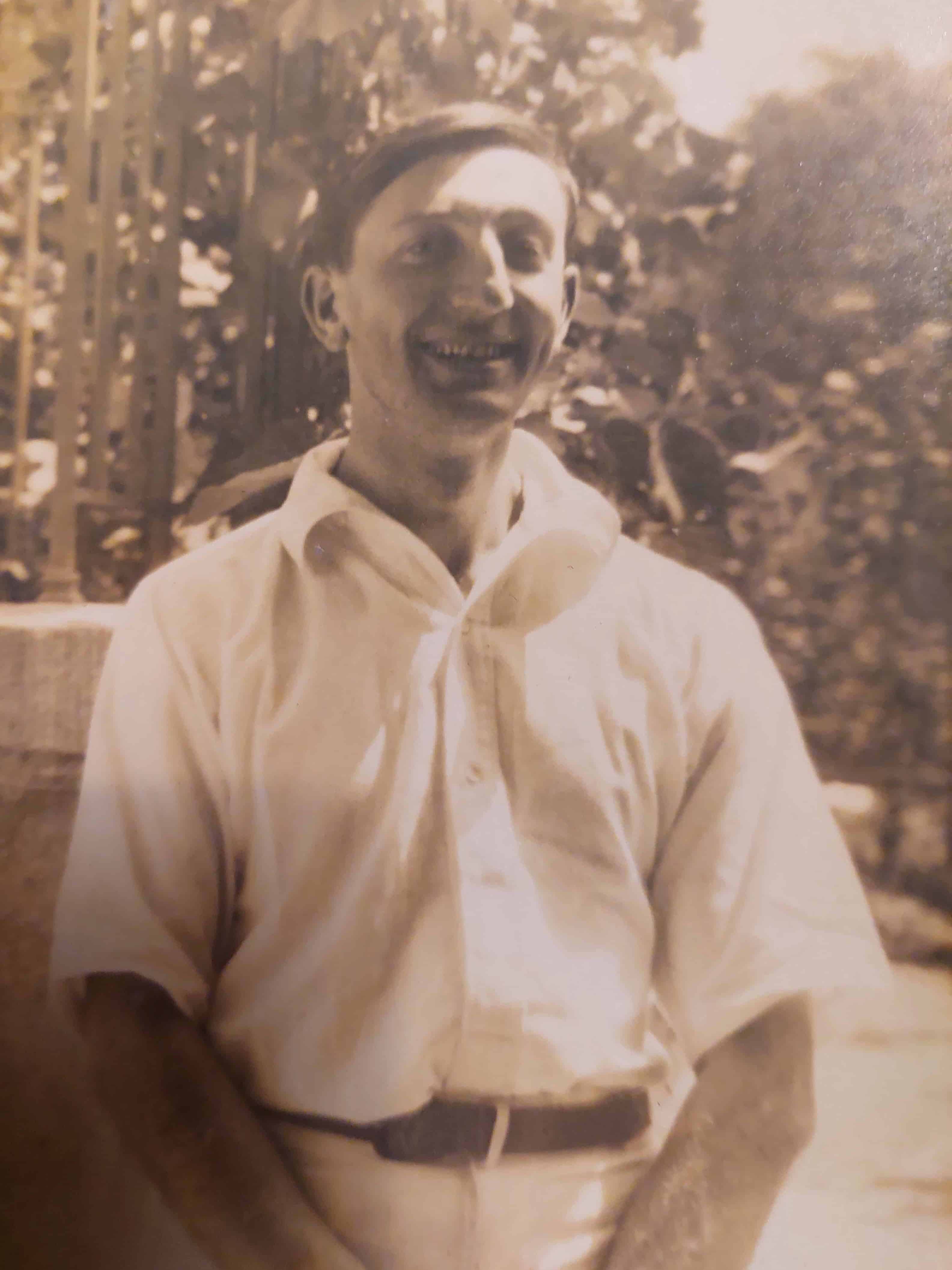

When I was a child, my father, Pál Hermann, lived in France. As often as his work allowed, he would come to visit us in the Netherlands. I still cherish some gifts he brought me: a doll which looked like Josephine Baker; books about the little elephant Babar. His last visit was for my seventh birthday, then war broke out – and after the war he did not return.

All his possessions were lost and only the Grand Duo for cello and violin, which my father played often with his lifelong friend Zoltán Székely, and a few piano pieces were printed. Thanks to my son Paul and some musical friends, it was possible to transcribe handwritten manuscripts into digital format. Also, several compositions were found in libraries, adding up to a total of over twenty available online for musicians all over the world.

The Toccata Classics project of the ‘Surviving Music of Pál Hermann’ breathes life into these pieces, and it is a wonderful experience to hear both the serious and the witty aspects of my father’s personality in this music – the dramatic songs, the vigorous Toccata, the surprising Épigrammes and the colourful string music. I am very proud and thankful that Toccata Classics has made it possible to keep Pál Hermann’s legacy alive!

Pál Hermann: The Complete Surviving Music

* Szentgyörgyi has been so roundly forgotten that a résumé of his career would seem to be in order. He was born in Budapest, in 1910, and had his first violin lessons from his father at the age of four; he entered the Franz Liszt Academy in Budapest at the age of ten, studying initially with Oszkár Studer and then, at the age of fourteen, entering the class of Jenő Hubay; that same year (1924) he won the Remenyi Prize and made his professional debut with Ernst von Dohnányi conducting the Budapest Philharmonic. He earned considerable success in Paris in 1930 and gave two concerts at the Salzburg Festival in 1931. He was then concert-master of the Budapest Philharmonic from 1931 to 1944; Professor at the Liszt Academy from 1940; concert-master in Freiberg in 1946–47 and of the Innsbruck Symphony in 1947–48 before moving to Tucuman, Argentina, in 1948 where he became head of the violin department at the local school of music and concert-master of the local orchestra, but in 1965 a stroke left his arm partially paralysed. He died in 1973. (Information, via Tully Potter, from John A. Maltese, Albert B. Saye Professor and Meigs Distinguished Teaching Professor in the School of Public and International Affairs, University of Georgia)