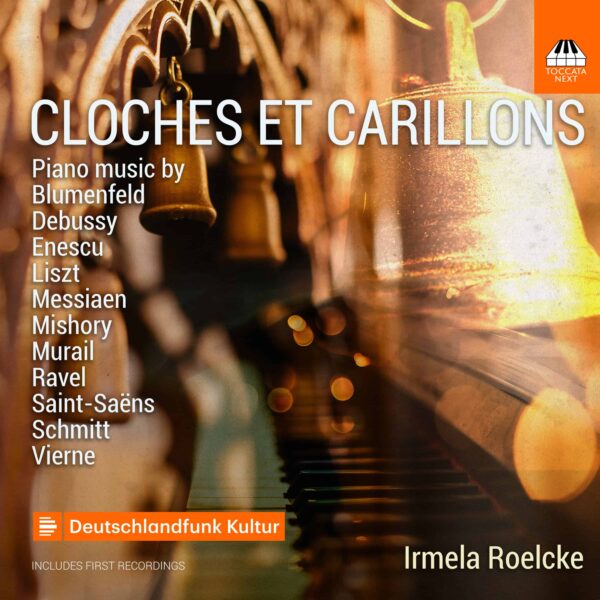

My concert and recording project, Cloches et Carillons, impressed on me how much basic acoustic characteristics have influenced my most recent artistic interests and inclinations.

I grew up in Heidelberg, in a quiet, middle-class residential district. My parents’ house is on a small street which has, at one end, the Evangelical Church of St John, and, at the other western end, the Catholic Church of St Raphael. In the morning at 7 a.m. the bells of the bell towers begin their daily work and continue to ring every quarter of an hour until 10 p.m. The time, measured by the help of well-ordered chimes, lent a distinct clarity and structure to every day of my childhood. There is a particular tonal relationship between the pitches of the bell sounds emanating from each of the two churches that I struggle to express in words, but which make a deep impression on me, because their sounds, as they spread out into the immeasurable vastness, dissolve into harmony and peaceful silence. This impact also applies to the speeds at which the different bells strike, which again and again result in completely surprising, complex metric shapes. No matter in which city I have lived or visited, the sounds of bells have always been important and ever-present companions throughout my life.

A few years ago I heard George Enescu’s ‘Carillon Nocturne’ for the first time and was immediately fascinated by its uniqueness and beauty, which resonated deeply with me. This experience encouraged me to deal with the subject in depth and professionally for the first time. Over the course of the ensuing few months, I collected numerous piano pieces from different eras and styles containing the title ‘Glocken’ or ‘Glockenspiel’, or which explicitly referred to them musically.

For the album Cloches et Carillons I have made a selection of pieces from the nineteenth century to the present day which illuminate different aspects of bell instruments. It begins with the evening bells by Camille Saint-Saëns, Les Cloches du soir, and Franz Liszt‘s ‘Abendglocken‘, the ninth piece from Weihnachtsbaum, followed by two further pieces by Liszt relating to the cities of Geneva and Rome. Bells are also instruments with a ritual function: Florent Schmitt‘s Musiques intimes, Op. 29, No. 6, ‘Glas‘, and Louis Vierne’s Poèmes des cloches funèbres, Op. 39, No. 2, ‘Le glas‘, present bells that are evocative of dying, death and transience.

The Russian composer Felix Blumenfeld also reflects on death knells in ‘Glas funèbre‘, the second movement of his bell suite, Cloches. Here a completely different culture and tradition of bell-ringing comes into play: you can hear the Russian bell walls (the equivalent of bell towers) – think, for example, of the Rostov Monastery. In their monumental form in the triumphal bells in the third movement, ‘Cloches triomphales‘, the sound is almost hypnotic.

Ravel and Debussy have incorporated an important element into their two works: the interface between natural sounds and the man-made, culturally charged bell sounds, which merge with each other and form a new unity in Ravel’s ‘La Vallée des cloches’ from Miroirs and Debussy’s ‘Cloches à travers les feuilles’ from his second book of Images. A triad follows, bound together by an inner thread: Olivier Messiaen addressed the bells of fear in his early Préludes from 1928, here represented by No. 6, ‘Cloches d’angoisse et larmes d’adieu’. Depending on the ringing order, they are rung on Maundy Thursday or on Good Friday and commemorate the agony of Jesus in the Garden of Gethsemane. In his Cloches d’adieu, et un sourire from 1992, Tristan Murail writes a kind of epitaph for his beloved teacher and takes up constitutive musical material from Messiaen’s Préludes. Gilead Mishory also alludes to Messiaen, but brings a completely different colour into play: his 2006 Cloches de joie et larmes de rire is funny and happy, full of wit and humour, but also quite anarchic.

The heart and the dramaturgical aim of the album are Enescu‘s ‘Choral‘ and ‘Carillon nocturne‘ from his Piano Suite No. 3, Pièces impromptues. One has to imagine that at the time this work was written (1913–16), the First World War was raging in Europe. Enescu was in Sinaïa, a small town in the Romanian Carpathians, writing a piece of timeless and breathtaking beauty. The chorale is initially reminiscent of liturgical singing in a monastery, but it also reaches more distant regions that seem almost improvised. Towards the end of the ’Choral‘, the first sounds of bells appear before the ‘Carillon nocturne‘ plunges into the atmosphere of the chorale. This music is truly outrageous. It has no role model that I know of in the history of music. The main melody is enriched with overtones, so that an impressive alienation effect occurs. The piano is no longer just a piano, it becomes a carillon. Just before the coda, twelve chimes ring out, for midnight. There is something so comforting, beautiful and valid about the farewell that follows, with the final exhalation embedded in harmony, peace and tranquillity.