Sometime in the 1950s, when John Barbirolli famously said ‘there are too many symphonies this year, or any year’, he might have been weary after having had to learn the current crop of works in that weighty genre in time for the Cheltenham Festival or The Proms. That decade found the idea of the ‘Cheltenham symphonist’ at its height, a term commonly used nowadays to describe a group of composers that might include William Alwyn, Arnold Cooke, Peter Racine Fricker and Edmund Rubbra, wedded to tonality and traditional forms – although I believe the epithet was a disparaging invention of Elizabeth Lutyens, along the lines of her other disdainful if amusing coinage, ‘cow-pat music’.

The mythology of the demise of symphony has its own easy catchphrases; an entity called in some quarters ‘the Glock regime’ apparently hoovered up with Stasi-like stealth any remaining sonata-form fuddy-duddies to make way for the never-oiled ‘squeaky gate’. Trilby-toting aficionados of Whettam and Wordsworth were sent reeling from the concert hall by the sight of Maxwell Davies’ Pierrot Players imprisoned in bird cages.1 Polarisation of traditionalists and modernists during the 1960s and ’70s coloured the debate in only black and white, and although it didn’t often reach the spite of the Brahms/Wagner spats of the late nineteenth century, this polarisation was proclaimed by louder voices than those who whispered in the back rows of London Sinfonietta concerts that they went from Boulez to Bax without choking on their interval peanuts.

So much for convenient pigeon-holes of style and genre. History is messier than the stuff you find in its books. Certain so-called modernists had no interest in banishing older forms or styles in the way the myths would have it; witness the symphonic cycles of Lutosławski, Maxwell Davies or Penderecki – whose avant-garde beginning (his stunning First Symphony), and his subsequent hazarding of an uneasy world where chromatic snakes climbed over the walls of Brucknerian cathedrals constituted a symphonic journey well worth following. That other composers did indeed eschew symphonic forms merely led them to other enriching ways to construct music, to the enhancement, not detriment, of the musical landscape.

Influences acting on composers don’t follow text-book genealogies, either; it might be easy to say contemporary music ‘progresses’ through direct lines of descent from the generation immediately preceding; for composers born from the 1930s onwards this route might mean the line from serialism or post-serialism, and yet composers can choose their own paths that skip not only generations but centuries. The map of influence has paths from Pérotin to Maxwell Davies, from Orthodox chant to Schnittke, and the dual-carriageway to Birtwistle has room for Schoenberg and Vaughan Williams to travel shoulder to shoulder. 2

All these considerations move the argument to a different position from those who would have all musical periods neatly sewn up, with supposedly opposing forces laid out like toy regiments on the living-room carpet; one might posit the alternative view suggested by M. L. Rosenthal in relation to another art form: ‘poetry can be understood one poem at a time only’. 3

Rumours of the death of the symphony have been exaggerated, then. There are, if not too many, certainly many symphonies; the form seems still to attract composer after composer (myself included). Economic factors may lead us to compose symphonies without thought of performance. Compulsion overrides hope. Those unlocked orchestras stacked up in heads… With performances difficult to come by, Toccata Classics is one among several record companies prepared to issue music that might otherwise remain beached on white paper; for example, in the last year or so Steve Elcock’s Fifth Symphony has been one such work that has been brought to light. I have already written about this symphony – and my enthusiasm for its coruscating attributes has not dimmed 4 – and in the last year other works have announced themselves on the symphonic radar with equal insistence.

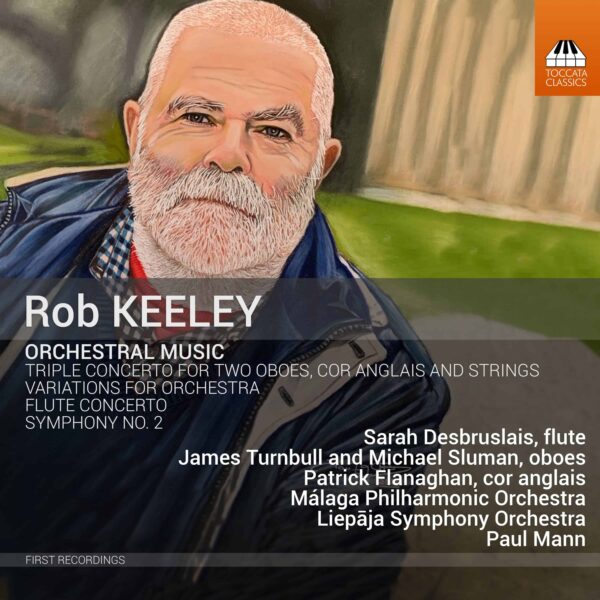

I first met Rob Keeley about fifteen years ago when he gave a piano recital of his own works and those of rather neglected composers in the basement of Schott’s in Great Marlborough Street in central London, the stand-out piece being André Jolivet’s Mana. I had previously been alerted to Keeley’s craft by his Ballade for piano that appeared on a Martin Roscoe Dunelm Records recital disc.5 I then got to know Keeley’s chamber music through a number of concerts and recordings. It is therefore an immense pleasure to hear what Keeley does with larger forces. His Symphony No. 2, dating from 1996, and released on Toccata Classics TOCC 0462, is in the usual four movements 6 – ‘usual’ in the structural sense that Keeley casts the work in two fast movements enclosing a scherzo and a slow movement – but the music is itself is far from ‘usual’. The characteristics of Keeley’s works – clarity, motivic cogency, a delight in the play of idea and texture – are all familiar from his chamber music. In the faster outer movements of the Symphony there is an endless spooling of motivic interplay; instruments jostle for attention, spar with their own jabs and hooks – it is combative music to a degree but within the confines of the rules that are set out in the first bars.

Turning to the influence map we might find Copland and Stravinsky in Neo-Classical mode – and yet Keeley’s music is his own. Another composer I would mention as a close relative to Keeley is Lennox Berkeley. Although I happen to know that Keeley’s knowledge of music is encyclopaedic, he and I haven’t discussed Berkeley, and yet it wouldn’t surprise me if he knew the work of this seemingly ignored but important composer intimately.

The scherzo of Keeley’s symphony has the strings scampering up a ladder of intervals (a distant cousin of the finale of Berkeley’s Fourth Symphony perhaps?) and we are subsequently treated to a series of luscious yet animated textures where a pair of flutes ride a bed of strings and harp – music of a distinctly French quality not so far from Berkeley. One knows where this music is coming from but it all sounds so fresh and invigorating.

The slow movement of the symphony brings a web of chords for divided strings with answers from piquant wind – a dialogue is set up between these two types of material that is both questioning and redolent of a pastoral landscape, one curiously populated with plaintive oboe cries. It can be pointed out that Keeley is one of the few composers who can write for oboes in parallel thirds without sounding like Sibelius; he is also capable of the most subtle sleights of hand harmonically – actually, the degree of dissonance is quite high but seems leavened with a coolness of approach that allows for edges to be smoothed. Keeley passes chords over each other so that incidental dissonance comes and goes in a kaleidoscope of colour. In this sense the listener might recall the iridescent textures of such Italian composers as Dallapiccola and Petrassi. Everything in this Symphony speaks of exactitude of craft and intense realisation of ideas.

It is worth mentioning the other large-scale piece on this Rob Keeley disc, the Variations for Orchestra, not a symphony but a work of symphonic stature. Here the non-Sibelian thirds get a real workout; passed from oboes to clarinets to horns where the intervals start to change, the theme itself is a wonder of quiet mastery. In a musical world where composers are desperate to throw the kitchen sink at every new piece, it is to be treasured that a composer can offer such richness and invention with an average-sized orchestra from which everything can be heard, where there is no over-writing and its pages are not festooned with five percussionists hammering con tutta forza. Each of Keeley’s variations is beguiling – most of the music is chamber-like in texture and avoids histrionics – and yet the whole piece has a culminating force that belies the apparent ease with which the ideas unfold. Keeley’s music exists beyond the double bar – memory wants to relive it, and so the recording goes on again and again. The Málaga Philharmonic Orchestra and the Liepāja Symphony Orchestra share the playing honours on the disc. And the conductor? It’s that maestro again – Paul Mann, who as ever brings his acute understanding of the essence of each work.

Anyone who enjoys this music will want to hear Keeley’s First Symphony; it can be heard on YouTube in an air-shot from a BBC broadcast. Written in 1995, it is a piece with tremendous energy and emotional power that hints at a troubled landscape. Two superb symphonies only a year apart, the second of which is like a considered answer to the stormy questions raised by the first. At the time of writing Keeley is working on a series of string quartets – it is to be hoped that these can be performed as soon as circumstances allow.

- As in Maxwell Davies’ own piece, Eight Songs for a Mad King.

- The late Justin Connolly liked to tell me of a conversation he had with Pierre Boulez during which they discussed Vaughan Williams; ‘very interesting composer’, said Boulez – before moving to other topics. At the time of his death in 2020 Justin was working on a symphony.

- M. L. Rosenthal, The New Poets: American and British Poetry Since World War II, Oxford University Press, New York, 1967; quoted in Eric Homberger, The Art of the Real, Dent, London, 1977, p. ix.

- On Toccata Classics TOCC 0445 together with Elcock’s Incubus, and Haven: Fantasia on a Theme by J. S. Bach.

- Dunelm DRD0247. This disc also contains fine performances of Schumann’s Kreisleriana and Chopin’s Ballade No. 1.

- Keeley’s Second Symphony, together with Keeley’s Flute Concerto, Triple Concerto, and Variations for Orchestra, can be found on Toccata Classics TOCC0462.