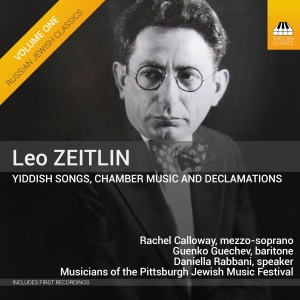

The story of Leo Zeitlin and his music’s re-emergence is so remarkable that it has already been duly reported in several online and printed articles. To add to these retellings, we now have Leo Zeitlin: Yiddish Songs, Chamber Music and Declamations (TOCC0294). As originally submitted, the album was brimming with biographical information, programme notes and translated lyrics. The booklet text was hefty enough but it did not mention how Zeitlin’s music was brought to light after his death. With Martin Anderson’s encouragement, the posthumous portion of the composer’s journey was ultimately included. This blog will relate how both that discovery and this album came to pass.

It was six decades after Zeitlin’s death that a trunk filled with meticulously hand-written manuscripts finally saw the light of day. It marked a rare moment when most of a composer’s œuvre was discovered all at once. Included were unpublished chamber and orchestral music, arrangements and original compositions. This album was released another 25 years after that.

Leo Zeitlin (1884–1930) emerged as an active figure during the Jewish nationalist movement of early twentieth-century Russia. He demonstrated a rare dramatic flair and idiomatic approach to setting Hebrew and Yiddish texts. Although active as an orchestrator, violinist, violist, arranger and conductor, only four short works of his were published by the St Petersburg Society for Jewish Folk Music. His American career, where he worked for the Capitol Theater – a grand ‘picture palace’ that regularly employed a large orchestra – was cut short by his death at age 45 from encephalitis lethargica (sleeping sickness), only seven years after he moved from Vilna (now Vilnius, the capital of Lithuania) to New York.

Fast-forward six decades. The Houston cellist Paula Eisenstein Baker was trying to determine the composer of a Jewish-themed cello piece, Eli Zion. The work is compact, tuneful and derived in part from authentic trope motifs – in this case, the musical fragments used to chant the Biblical ‘Song of Songs’ (Shir hashirim).

Erroneous information indicated that the composer was a Moscow-based violinist named Leb Moisevich Tseitlin. Eisenstein Baker was convinced otherwise – that Eli Zion was written by a Leo Zeitlin who was born in Pinsk, Belarus, and had died in New York. Once she located his gravestone in Queens inscribed with the theme of the very piece she was playing, she had proof that Zeitlin was a forgotten composer about whom next to nothing had been written or published.

Zeitlin’s daughter Ruth had been keeping a trunk filled with her father’s papers stored in her attic in Los Angeles, unsure of what to do with the contents. Her meeting with Eisenstein Baker was fortunate, to say the least (Baker tracked her down the old-fashioned way: trial and error, using a phone book). It resulted in a scholarly publication of Zeitlin’s complete known chamber music (Leo Zeitlin: Chamber Music, published by A-R Editions, co-edited by Eisenstein Baker and Robert S. Nelson). These 27 short works provide a window into a lost world of Yiddish culture and reveal a previously unknown voice in Jewish art-music.

Eli Zion proved to be the tip of the iceberg that led Eisenstein Baker to many other works by Zeitlin. And this same piece lead me to discover the music that became this first Pittsburgh Jewish Music Festival album.

I created the Festival as a forum for what I knew to be an under-appreciated and interesting catalogue of Jewish-themed classical music. I believed I had scoured the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh for every relevant score. Newly added to the stacks, though, was this thick collection. Because I am a cellist, Eli Zion was the only piece I was immediately curious about. To my surprise I found it in on the Collected Works shelf. The six-minute piece was published in the middle of an entire volume’s worth of pristinely printed scores by the same composer, parts and all!

This Zeitlin collection seemed tailor-made for the Festival. The Yiddish songs would speak directly to those who had a familiarity or nostalgia for the language. The orchestrations were sophisticated enough to showcase the playing of the Festival’s high-calibre players. The diverse instrumentation allowed for a constant rotation of musical chairs. A roster of a string quartet, piano, two singers and speaker would be shuffled in a variety of combinations.

Another benefit of performing most of this chamber-music collection was convenience. So much of the so-called ‘Jewish’ repertoire can be unpredictably complicated. Old and new scores are invariably riddled with mistakes, discrepancies, and ambiguities. Such challenges necessarily arise from an improvisatory style and a lack of a performing tradition outside the classical canon. This lack of tradition puts a further burden of research and decision-making on the musician. In this thoroughly transcribed and researched volume, the work required to make Zeitlin’s music performance-ready had been done for us!

It was winter, and – as usual – I had procrastinated in making final programming decisions for the annual spring concerts of the Festival. The only thing I knew was that the theme for 2010 was going to be the Yiddish language, as expressed in popular song and art song. This newly discovered volume fitted the bill and looked promising, but was the music any good?The first person to contact, of course, was Paula Eisenstein Baker. Fortunately, finding her was considerably easier for me than it had been for her to locate Zeitlin’s daughter 25 years before. By coincidence she had plans the following week to visit New York, where I was living at the time. She brought with her some audio and video recordings of previous performances she had organised in Houston. Coincidentally, a like-minded organisation in Washington, D.C., called Pro Musica Hebraica had recently done five of the Yiddish songs with strings. Those live recordings quickly answered the question of which singer to use. In Houston, as was likely the case in Russia, the songs were sung by a male voice. But we agreed that the timbre of mezzo-soprano Rachel Calloway, based on her dazzling turn in D.C., suited the repertoire perfectly.

In a few months, an intricate programme with many moving parts was thrown together. Nearly every vocal-instrumental piece in the published volume provided the basis for what became an evening-length tribute to Zeitlin called ‘Hidden Yiddish Treasures’.

Up to this point the Festival had presented only live concerts; I had never considered producing a recording. Both the live performance and recording were opportunities, though, to present the work of a single composer in a unique way. The album would copy the order of the live programme, which was carefully selected for flow and variety. All the pieces were short and represented a range of instrumentations and styles. A simple folksong, for instance, would be offset by a dramatic melodeklamatsiia, or declamation: a combination of spoken words and original piano music in a late Romantic style.

A tumultuous depiction of The Sea (More, in Russian) would open the concert. The idea was to grab the audience with its Rachmaninovian piano writing, underscoring a Russian poem powerfully declaimed by our Bulgarian baritone, Guenko Guechev. The work ends on a climactic piano tremolo, which plunges us into the string quintet Reb Nakhmons nign, where all five instruments play a dramatic melody in strict unison. This brief work would fade into the mysterious Tsien zikh khmares oyf, hart mayns (‘Clouds sweep upward, dear heart’), the first Yiddish declamation of the evening. Fortissimo open strings would then announce the longest work, Iber di hoyfn (‘Over the fields’), that introduces Rachel singing along with Guenko, accompanied by a string quartet. As the open strings fade away ‘over the fields’, we segue to a whimsical Yiddish declamation with piano. And so on: the programme was designed like an album, to be considered as a whole piece.

Presenting such a high-concept programme was an exercise in trust for both the audience and me. A screen to the side of the stage displayed a polite request to not applaud until intermission. English translations of the texts were likewise displayed as supertitles, timed with the performance. This window into a forgotten world demanded an attentive leap on the part of the listener.

Unfortunately, I underestimated the steps that might be needed to create the experience of hearing a ‘live CD’. A prepared spiel to introduce the genre of declamations would have gone a long way. As it happened, the audience did not know what to make of the first Russian poem. Powerful piano chords occasionally overwhelmed the text; was everyone supposed to be able to make out every syllable? This was a Jewish music festival – did they even realise that this first work was spoken in Russian, not Yiddish? Was it a mistake to only include the English translations on the supertitles, and not transliterated lyrics as well?

In spite of the printed request, there was clapping after each piece, which interrupted the intended segues. Then there was shushing of the clappers, which further interrupted the flow. But the confusion came to a head just as we started A mayse (‘A Story’), a serene berceuse in the tradition of Yiddish lullabies that express adult themes like loss. A man rose from the rear of the auditorium and approached the stage in his shorts and dark socks.

‘Close the lid of the concert piano!’ he shouted, now standing directly in front of the musicians. His outburst was met by murmurs of both protest and agreement from the crowd. My face was flushed as I reluctantly lowered the lid down to the half stick. No matter that the loudest work for piano was over, that the work we had just begun didn’t even use piano, or that after the first problematic Russian declamation there would have likely been no further balance issues. The damage was done, and the thread of our Zeitlin survey had been ruptured.

The good news was that we had managed to schedule recording sessions around that concert. The final product would, if successful, create the intended uninterrupted listening experience. With a copy of the CD in your hands, you can listen to the four declamations back to back. You can listen to the Yiddish songs clumped together, or isolate the few instrumental works. Or you can let the disc play through and imagine the ever-rotating musical chairs on stage, each piece setting up the mood for the one to follow. Most importantly, you can read along with the transliterated Russian and Yiddish texts and their English translations and know that, to the best of our abilities, all balance issues have been taken care of.

This Zeitlin album represents the intersection of a scholarly publication and a live concert. Thanks to Toccata Classics, Leo Zeitlin’s legacy is now enshrined in a polished and permanent document. I hope that it may bring listeners enjoyment and inspire further interest in his life and music.

The original “Eli Zion” is one of the mournful traditional song-poems of the Tisha B’Av morning service.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jb89N-uPqwI