In the autumn of 1959 I was beginning my final year at Oxford. A friend called David Tempest, like me a piano nut, asked me to come round and listen to a couple of new LPs he had just acquired: recordings by a pianist of whom neither of us had previously heard. The records in question proved to be two 10-inch Deutsche Grammophon discs, one of Rachmaninov Preludes and the other of a couple of Schumann Novelleten plus the Toccata. Reared since childhood on a diet of Solomon, Denis Matthews, Myra Hess, Lipatti, Schnabel, Moiseiwitsch, Brailowsky et al., I had never heard anything like these performances, not even the Horowitz recording of Rachmaninov’s Third Piano Concerto. All of the foregoing, except Lipatti and Schnabel, I had heard at one time or another in the flesh and was able approximately to relate the live experience to what I could hear on disc, even the 78 rpm shellacs, mostly second-hand and listened to on a wind-up gramophone, which until the past few years had been my chief musical diet. Now, David and I could not rest until we could hear this astonishing pianist, whose power, velocity, imagination, diversity of tone, ability to move seamlessly from explosive violence to melting lyricism and back while maintaining a convincing sense of structure, seemed altogether of another order than his peers. More than fifty years later, what I have just written in that last sentence would not, needless to say, be how I would try to express my feelings about the playing of Sviatoslav Richter because its qualities are so much more all-embracing. In fact, today I wouldn’t make the attempt at all, but that was the overwhelming impression I carried away from hearing those DG recordings (made, I now know – thanks to the invaluable and exhaustive discography compiled by Falk Schwarz – in Warsaw earlier that same year).

Of course, at the time our burning desire to hear this new colossus live seemed destined to remain an unrealisable fantasy. It didn’t take long to discover that the Russian pianist Sviatoslav Richter had never appeared anywhere in the western world, and the general opinion was that – whether from a personal disinclination to emerge from the cloistered world of the Soviet bloc or from the refusal of the regime to allow him to travel was not clear – there was little prospect of his doing so in the foreseeable future. It only added to the general air of mystery: where had this extraordinary being sprung from, fully formed? Was he to be forever immured in the inaccessible Soviet Union? I turned my attention to my final-year studies, got my degree in French and Russian, and set about trying to find a job somewhere, it didn’t matter much where as long as it was something to do with music, the only arena which held any interest for me.

Despite my obvious lack of qualifications for this profession, I was lucky. Because I could speak and write Russian, at the time still a comparatively rare accomplishment, I was taken on as general assistant and dogsbody, duties unspecified, by Victor Hochhauser, the impresario who since Stalin’s death in 1953 had already succeeded in bringing to London several Soviet luminaries including David and Igor Oistrakh, Rostropovich, Rozhdestvensky, the Red Army Choir, an ensemble company of the Bolshoi Ballet, and so on. In the planning stage were such monumental undertakings as the Leningrad Philharmonic with Mravinsky and a five-week season at Covent Garden by the Kirov Ballet. For such a high-profile enterprise, not to mention the more routine offerings they presented to the public on a regular basis, the Hochhauser office was surprisingly small. In 1960 it consisted of Victor himself, me and a secretary. I don’t believe Victor had ever previously had an ‘outsider’ working in his office; he and his wife Lilian had always done everything themseles with no more than clerical help. (This minimalist approach to administrative overheads is still, by the way, very much a feature of the Hochhauser operation: as has been the case from its inception to the present day, there was also an eminence grise in the shape of Lilian, but at this particular juncture she was obliged to be home-bound for much of the time because their youngest child, Daniel, now Kathleen Ferrier Professor and Consultant Medical Oncologist at University College Hospital, was still a baby requiring full-time attention.) For me it would be hard to imagine a more productive, or a more demanding, testing ground for a novice concert-manager with a passionate but untutored interest in music but zero experience of how it is actually produced for public consumption.

Mirabile dictu, about a year after I started work in the Hochhauser office, indefatigable probing by Sol Hurok in New York and Victor in London, which had been going on for some years, unexpectedly found a chink in the stone wall of official Soviet resistance to the idea that Richter could appear in the west, and in October 1960 he duly arrived in New York to give an unprecedented five Carnegie Hall solo recitals in twelve days, all with different programmes. The phenomenon was incontestably real. Papers recently made available from Soviet government archives reveal that permission was granted only after protracted and vehement debate between Minister of Culture Furtseva, who wanted it, and the Central Committee of the Communist Party, which decidedly did not. Richter’s own inclinations do not appear to have been material considerations; it would have been entirely in character for him to be indifferent, except for the prospect of meeting again his mother and other members of his family with whom he had had no contact for almost twenty years.

The Carnegie Hall recitals were a prelude to an American tour which sensationally confirmed the extravagant expectations aroused by the recordings and travellers’ tales from behind the Iron Curtain. The word was made flesh, and Richter was now a known quantity in the west. Victor announced that he would appear in London in the summer of the following year. I still could not quite believe that I would be able not only to hear him in person but probably meet him. But lo, in July 1961 I was knocking on the door of his suite in the Kensington Palace Hotel, down the road from the Albert Hall, about to show him the proofs of his Festival Hall recital programme. Mentally rehearsing my Russian in order not to dissolve into agonising tongue-tied star-struck adulation, I must have managed not to make too much of a fool of myself, since as the visit progressed and I fulfilled my role of bag-carrier, chauffeur, interpreter and general temporary amanuensis, there grew up, I cannot say a friendship, but at least a tolerance on Richter’s side of a useful, occasionally amusing and above all undemanding companion.

Although a couple of years later I officially moved on from the Hochhauser office, I always made sure that in whatever employment I found myself I would be able to get time off to be on hand whenever Richter was in the country, which happily became more frequent during the 1960s. I also visited him in Moscow, and because I had had several summer jobs working in the Aldeburgh Festival office, it seemed natural for me to be with him when he was invited there. In a place like Aldeburgh Richter preferred to stay in modest private accommodation rather than luxurious hotels where he was liable to be accosted by well-meaning fans, and we usually stayed with the unforgettable Barbara Grayburn, where he could completely relax, practise whenever he liked, spend time with her dogs and go out in Barbara’s husband Bill’s fishing boat. (Bill, to Richter’s delight, had early on announced that he knew nothing about music and actively disliked it.) The Suffolk countryside and villages were an unfailing attraction and we drove around it looking for out-of-the-way places to walk and find unpretentious tea-shops and pubs. In this way I became a sort of accepted presence, and no doubt on this basis he asked me in 1965 if I could get leave of absence from my work (by then I was working at Rosehill, an arts centre in Whitehaven in West Cumberland) to accompany him to the United States for a second Hurok tour. As he said, he wanted to have someone from le vieux continent to provide some kind of buffer from the American way of doing business (particularly the business of music) and the social obligations routinely imposed on its star performers.

Naturally, I jumped at the chance. It was to be a long tour, coast to coast, and Richter wanted, nay insisted, on travelling everywhere either by train or car, never by air. I had never expected to find myself behind the wheel of an enormous powder-blue Cadillac convertible with fins and chrome, but that was our transport from New York as far as Chicago, after which we continued to the West Coast on the Santa Fe Railroad. I can’t remember how we got back east, but presumably the same way. I loved that car and the Rand McNally road map needed for our odyssey. Richter always said he had no interest in America except for its art museums, its orchestras and its cocktails. These three manifestations, particularly the first, and the more recondite examples of the third, were, I must say, explored in considerable detail.

This trip was where I first met those close members of Richter’s family who had been evacuated from the family home in the Ukraine to Germany in 1943 because they were entitled to claim some element of ethnic German ancestry: his Aunt Meri and Uncle Kolya and his cousins Fritz and Walter, all of whom (but not Richter’s mother Anna, who had fled to Germany from Odessa two years before her relatives) had emigrated to the States after the war and were living near Boston. Richter himself had been out of the Ukraine since 1937, when he took himself to Moscow to study with Heinrich Neuhaus at the Conservatoire. During the 23 years separating 1937 from 1960, except for a couple of summer visits home before the German invasion of 1941 after which travel and indeed communication of any kind was impossible, there had been no contact whatsoever. Richter had no idea until after the end of the war that his father had been executed by the NKVD in Odessa by 1941, nor that his mother had fled to Germany and had married again.

Richter talked often about all these relations, although less about his father and still less about his mother. The most important person seemed to be his mother’s sister Meri (an affectionate diminutive of her baptismal name Tamara). She was the one most often in his thoughts, and with whom he was most inclined to be in correspondence. Readers of our book will understand why this was. When we were all together at Easter-time in Boston in the middle of the tour, I was personally utterly captivated by her, and was very glad that when she came to Europe (at Richter’s invitation) in 1977 I was able to see her again and spend time with her. I also met for the first time Walter, like Richter her nephew but much younger than his famous cousin. I did not get to know him well until much later, only a few years ago in fact, when we began working on a book to celebrate his and his cousin’s family and in particular the influence of Aunt Meri.

Here there is a biographical circumstance that needs to be explained: in 1917, when the two-year-old Svetik (as the family always called him, rather than the affectionate ‘Slava’ by which he was known to others who, whether justifiably or not, considered themselves on intimate terms) became separated from his mother and father for a period of about four crucially formative years. Parents Teofil and Anna Richter were in Odessa where Teofil taught at the Conservatoire; Anna had taken her infant son to visit her family in Zhitomir where he contracted typhus. Simultaneously Teofil fell ill with the same disease in Odessa, and Anna was forced to leave her son behind to return and look after him. It was of course intended only to be a short separation, but revolution and civil war combined to make it impossible for Anna to get back to Zhitomir until late 1920 or early 1921. All this time Svetik was in the care of his unmarried aunt Tamara (Meri, Anna’s sister), and the emotional bond that grew up between them lasted until Meri’s death in 1984, untouched by the gulf between the USSR of Stalin, Khrushchev and Brezhnev and Meri’s eventual home in the USA. The stories Meri, a gifted illustrator and teller of tales, endlessly invented and told to the little boy are the key, exemplifying the world of the imagination she opened to his enthralled gaze. They were and remained central to his imaginative life, and I do not think it fanciful to see storytelling as the core of Richter’s music-making and the reason for its unmistakable individuality.

We have reached the point when I must try to explain the roots of the book Walter and I have now produced. Since my first encounter with his art, more than fifty years ago, when I knew nothing at all about his background, his training or his life, I was never able to understand where either his prodigious technical command or his unique interpretative insights can have come from. Not from a teacher or a sustained course of study, that’s for sure. Certain biographical and personal facts emerge piecemeal which when put together made him appear even more remarkable than at first appeared: he had practically no formal instrumental training whatsoever until he was nineteen, when he abruptly decided to convert his self-taught facility for sight- and score-reading into a concentrated activity as a pianist. (One cannot use words like ‘career’ and ‘ambition’ when speaking of Richter, since they are concepts that are almost completely lacking in the Richter make-up.) He did this by going on his own initiative to Moscow, in itself a remarkable feat in 1937, the apogee of Stalin’s Great Terror, to study with Russia’s most celebrated piano pedagogue Heinrich Neuhaus. The story is well known, but nonetheless true, that Neuhaus, on first hearing the undocumented, untrained young man play who had arrived unbidden in his class at the Conservatoire, stated that there was nothing he could teach him about playing the piano. This is not to say that Richter could not learn anything from the elder man, such is clearly not the case as Richter consistently acknowledged. But what he learnt was not how to play the piano, it was how to live, how to think about music, how to connect to and absorb the incredibly rich intellectual, literary and artistic community of Moscow at the time, in which Neuhaus was a commanding and polymathic figure. I can testify to the fact that he invariably placed a photograph of Neuhaus on the desk when he practised. From this I draw the conclusion that he consciously wished the spirit of Neuhaus to inform his conception of the music he was studying.

Other Richter characteristics in no particular order: an encyclopaedic knowledge not just of piano literature but of the whole symphonic, chamber music and operatic repertoire; a deep acquaintance with Russian and European literature; an abiding and well-informed passion for film and theatre, similarly not confined to Russian; an almost total disregard for politics and for the accepted norms of behaviour in the Soviet polity; a detailed knowledge of art and artists together with considerable abilities as a painter himself; an instinctive tendency towards reclusiveness and an almost pathological aversion to personal display which coexisted with a love of shared conviviality in the company of chosen friends. And above it all, an ingrained and sovereign assumption that the only way to get at the truth of anything, whether artistic or social or personal, is to think it out for yourself and have no truck with received ideas however widely shared or plausible.

There was also an almost childlike craving for adventure, risk, danger, perhaps born of a longing to recreate the excitement of hearing the stories his aunt had told him as a child, which he never forgot. We were in Chicago, weren’t we, so of course we had to go out to Joliet to see the Rialto Square Theatre, the Correction Center and the rail station where Al Capone had been apprehended. We followed the trail of well-known mobsters’ homes, and tried but failed to find the site of the Valentine’s Day Massacre. In New York, where we stayed at the Stanhope Hotel on Fifth Avenue – chosen for its proximity to the Metropolitan Art Museum to which Richter paid a daily visit – he several times went across to Central Park at night to see what might be happening in the less frequented areas, exactly the sort of thing tourists are warned never to do. One evening Lorin Maazel, who was also staying in the hotel, came to the suite to ask where Slava was. ‘Oh, he’s gone for a walk in the Park.’ ‘My God,’ said Maazel, ‘I hope he has a gun with him.’

Normally Richter would run a mile from an importunate fan who would simply take up time; part of my job was to try to keep such people away. One who was allowed to penetrate the wall was Dagmar Godowsky, daughter of Leopold and niece of Josef Hofmann, in her day a famous beauty who had had a Hollywood career as a silent screen vamp and claimed scandalous liaisons with a series of more or less notorious celebrities. ‘Tell me, Dagmar, how many husbands have you actually had?’ ‘Two of my own, darling, and several of my friends’!’ By the 1960s the famous beauty had collapsed to be replaced by a fearsomely witch-like presence, but the fund of stories was still full of wicked life and a constant source of pleasure. Dagmar represented the whiff of danger and rebellion that so appealed to him.

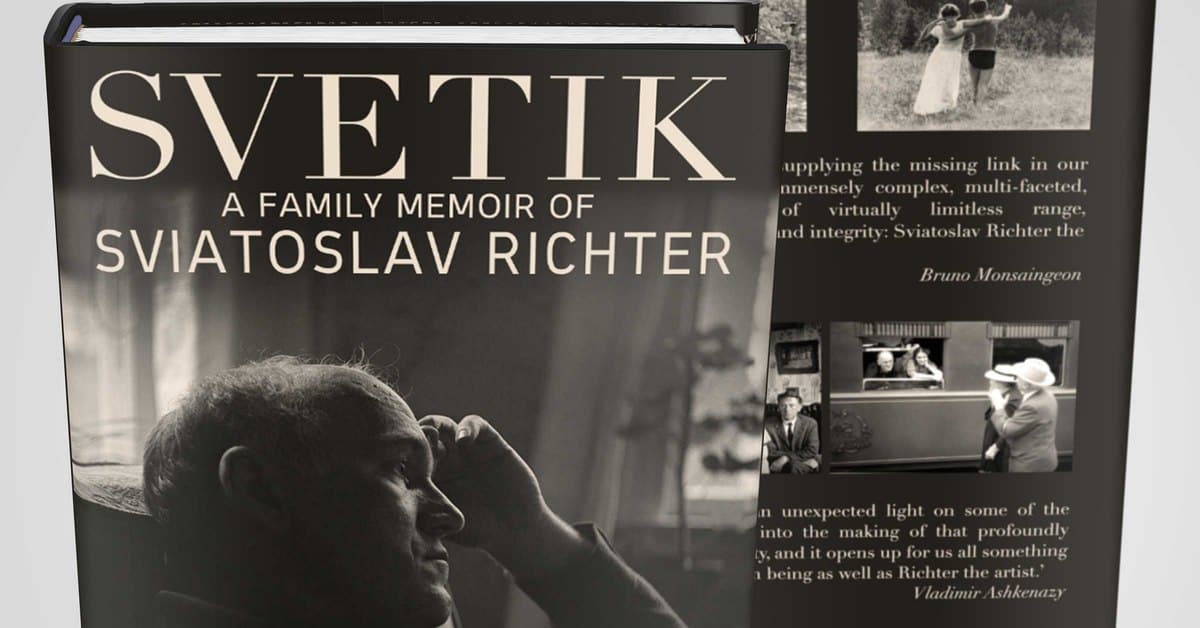

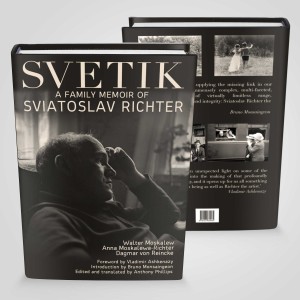

Where did such an extraordinarily vivid and contradictory mix of talents and characteristics come from and how could they have amalgamated to form the personality that was Sviatoslav Richter? I truly believe that if, as seems to me to be the case, Richter’s playing transcended the normal parameters of even the greatest executants, the explanation lies somewhere in the family in which the little boy Svetik grew up in a provincial city in the Ukraine, and most of all in the aunt who nurtured him and told him stories in those crucial years when war and revolution separated him from his parents. That is the story Walter and I have tried to tell in our book.

Very clear and informative description of experiences with my lifetime hero that I would have loved to have had.