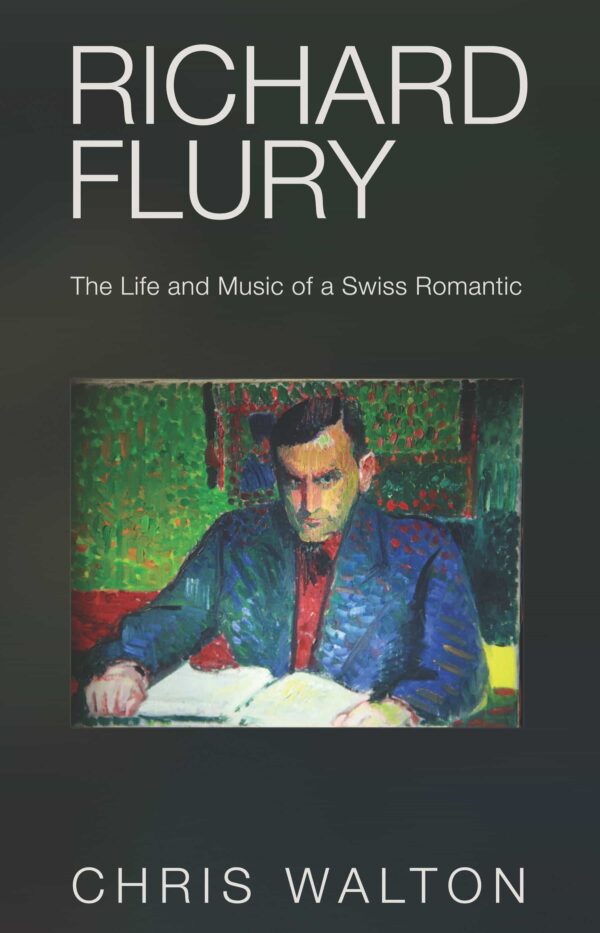

Richard Flury: The Life and Music of a Swiss Romantic

Discovery Club Members save even more!

Login or Join Today

Author: Chris Walton

Extent: 328 pages

Size: 16 x 24 cm

Published: March 2017

Illustrations: 22 colour illustrations; 51 b/w illustrations

The late-Romantic composer Richard Flury (1896–1967) was born in Biberist, a tiny town outside the Baroque city of Solothurn in northern Switzerland. He went to school in Solothurn, later taught there, conducted its orchestra, and had his operas and ballets performed at the local theatre by its semi-professional ensemble. But Flury was more than just another conservative composer stuck in the provinces. His teachers included Ernst Kurth and Joseph Marx of Vienna, and his music was performed by conductors such as Felix Weingartner and Hermann Scherchen and star instrumentalists like Wilhelm Backhaus and Georg Kulenkampff. His first opera was conducted by a former student of Berg and Schoenberg who became his staunch advocate, and during the Second World War Flury worked closely with several Jewish emigré writers and musicians from Germany and Czechoslovakia. In his music of the early 1930s, the influence of Berg and Hindemith became apparent as Flury dabbled in modernism and free tonality before moving back to a more traditionalist stance; but he was also a fine tunesmith who loved writing Viennese waltzes and violin miniatures after the manner of Kreisler. In both his aesthetic and his career, Flury offers a fascinating case of a man negotiating constantly between the centre and the periphery – and composing some very good music in the process.

Chris Walton, born in 1963, studied at the universities of Cambridge, Oxford and Zurich and was a Humboldt Research Fellow at Munich University. He was head of Music Division at the Zurich Central Library for ten years, during which time he also lectured at ETH Zurich and worked as an occasional répétiteur, continuo player and conductor. He then spent several years as Professor and Head of Music Department at the University of Pretoria, and today lectures at the Musikhochschule Basel and heads a research project at the Bern University of the Arts. In 2009 he was awarded the Prize of the Max Geilinger Foundation for his contribution to Swiss-British cultural ties. He has published several books on Austro-German music from Wagner to Berg. He lives in Solothurn and Törbel in the Swiss Alps.

David Brown :

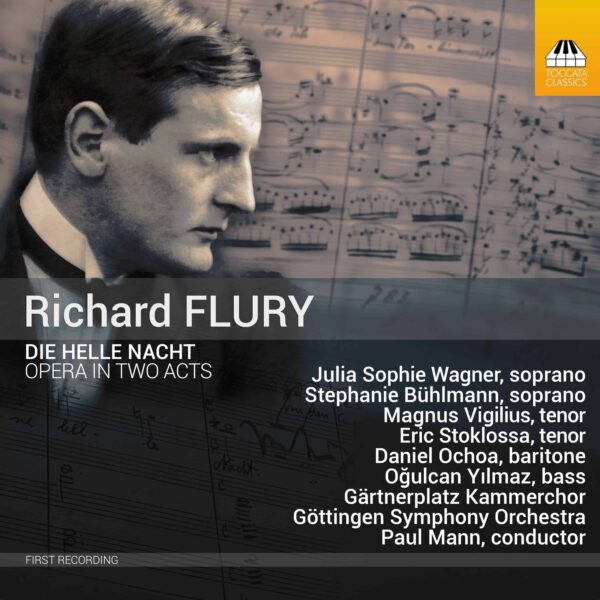

This book is everything that such a “life and music” study should be. Highly readable purely as a narrative, it balances the two aspects very skilfully, scrupulous about sources for the former and obviously written after deep study of the latter even though, inevitably in a concise 240-page text, you find yourself wanting more detail on many of the pieces (e.g. having found out that Paul Mann and the Nuremberg SO have just recorded the ballet “Der magische Spiegel” for future issue on Toccata Classics, I went back to these pages for more about it only to find a single mention, that I’d passed by in my reading).

Mr. Walton isn’t afraid of criticising the music, indeed I wonder whether he’s bent over backwards somewhat not to seem to overpraise many works in Flury’s very considerable output (putting me slightly in mind of Imogen Holst’s strictures on some pieces of her father’s that subsequent recordings have shown to merit much more favourable opinions than hers—would that we may one day have the opportunity similarly to find out for ourselves in Flury’s case).

As a piece of book production, too, this is exemplary and a joy to handle. Solidly hard-back, printed on a very white paper stock, with numerous well-reproduced sepia photos, cartoons, sketches, and posters (some in colour) for historic performances of Flury’s works, it also has a fair sprinkling of music examples, and copious appendices that would grace many a heftier volume. Most importantly there’s a complete catalogue of Flury’s works in genre categories, including date of composition, first performance when there was one, text sources for vocal works, and detailed instrumentation for everything involving orchestra. Following this is an index of the works, and then a general index.

Finally, the very substantial cherry on the top—actually tucked into a sleeve inside the back cover—is a CD of (mostly extracts from) Flury’s works, running to 83:40, covering all genres in his output and arranged chronologically from a very early song of 1918 to a movement from his 1965 Nonet. These are mostly taken from non-Toccata CDs, private recordings, and Swiss radio tapes, including the final couple of minutes of the opera “Eine florentinische Tragödie” recorded in 1944 which made me only sorry that Toccata’s scheduling precluded a mention of their marvellous recording of the complete opera by the Nuremberg SO under Paul Mann that appeared shortly afterwards.

I couldn’t recommend this book too highly for those with a taste for nosing out the unknown and forgotten, and that’s surely the defining characteristic of Toccata’s readers and listeners!

Muzik Zeitung :

‘Chris Walton thought he could hear Solothurn’s musical motto himself when writing his Richard Flury biography in English, which is well worth reading and based on extensive unpublished material. […]

It takes a good 200 entertaining, richly illustrated and strictly chronological pages for Fleisch to get to the romanticisms of the composer, born in 1896, already mentioned in the book title.’

—Christine Fischer, Muzik Zeitung

Musical Times :

‘Professor Walton, himself a most engaging writer, beautifully evokes the provincial musical life, rural culture and landscapes of the German-speaking part of Switzerland in the first half of the 20th century.’

—Andrew Thomson, Musical Times