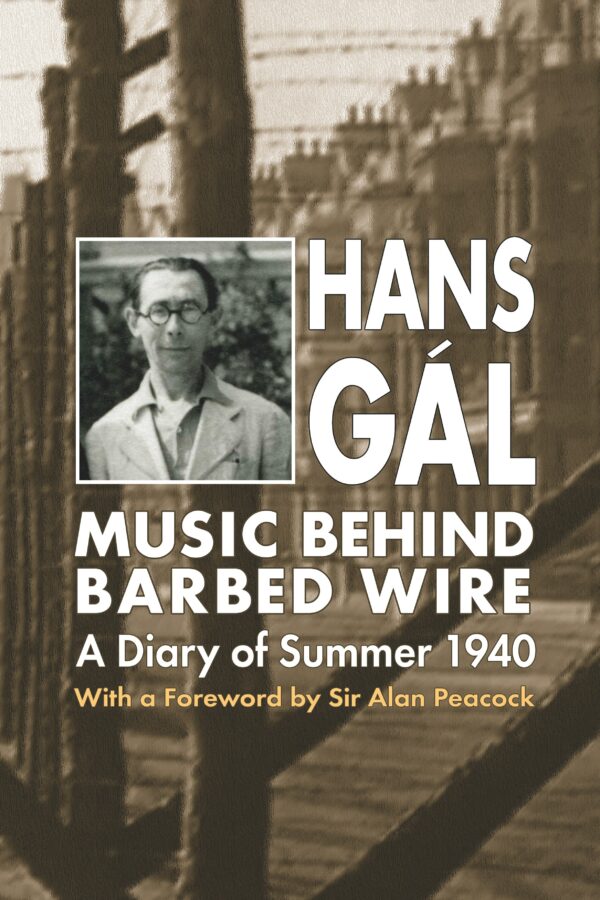

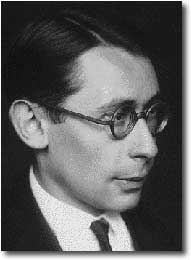

This conversation, first published in the Journal of the British Music Society (Vol. 9, 1987, pp. 33–44), was recorded at Dr Gál’s Edinburgh home in December 1986, less than a year before his death on 3 October 1987 – and long before Toccata Classics and Toccata Press could break a lance for his music. It shows his wit and wisdom undiminished by age. As a performing musician, too, he was in full command of his faculties: he sat at the piano and played me some Bach with extraordinary sensitivity of touch. The gentle humour evident in his conversation had already surfaced in an exchange before I began recording our talk. I asked him: ‘There’s a rumour that you played the piano to Brahms – is that true?’ His answer stopped me in my tracks: ‘What do you think? I was only six when he died’.

Although you are Austrian by birth, Gál isn’t an Austrian name, is it?

Gál is an Hungarian name. My father was Hungarian.

Had he settled in Austria by the time you were born?

He came to Vienna as a student, and became a doctor of medicine. It was a middle-class family. Both my grandfathers were doctors, too – it was a family of doctors.

Were you then, like Berlioz, destined to become a doctor, and not a musician?

No, no. I never intended to become anything else. In this respect my feelings were perfectly in balance when I left school at eighteen.

Did your parents help you?

My parents couldn’t help me much. Right from my student time I had to make my own existence as a teacher. I had pupils in Vienna from the age of eighteen or nineteen.

Were you composing already?

Oh yes. I started composing at eleven or twelve, and during my years at secondary school I wrote an awful lot of music.

All of which, I believe, you have since disowned.

I disowned them very soon, all these early works. I must have written towards a hundred songs around then.

So how old were you when you composed your first acknowledged composition?

Only after having had my sound training – not at the University: one didn’t get a musical training at the University. One could go to the Conservatoire, which I did not, or one could have private tuition, which I had. My teacher was Mandyczewski.

You collaborated with Mandyczewski on the Brahms edition, didn’t you?

Later, yes; but I became his pupil when I was nineteen.

Which made you a ‘grand-pupil’ of Nottebohm. Did you know Robert Fuchs at the Hochschule?

Yes, Fuchs I knew personally. He taught at the Conservatoire. My only teacher was Mandyczewski. I became a musician in every respect during my early twenties, but by the time I had become ‘mature’ the First World War started, and after a year I was in the army.

What were you doing in the army?

I had different occupations, but after the first few months was not in the front line any more. I had to do with administration and things like that, with war prisoners. I got round all the different parts of the War in the Austrian army: I was in Serbia, in Hungary , in Poland , in Italy .

Was your suite of Serbian dances based on what you heard there?

Yes, the Serbian Dances came from that time in Serbia, when I was travelling round the country. At the end of the War I was in the Austrian part of Italy. It was not a joke, you know: it was a very convulsive time, the end of the Austrian monarchy in 1918, when it fell into pieces. One has forgotten this part of history, you know. Austria was the only country in Europe at the time of the First World War without a parliament. Parliament had become a problem of different parties working against one another. It was not workable, and so it was dissolved in 1912. Austria was then ruled by a Prime Minister, who was never elected: he was nominated by the Emperor. Then the old Emperor died towards the end of 1916, and in the spring of 1917 the young Emperor, Karl, convoked the parliament – and the first thing the parliament did was to dissolve the monarchy. This was the situation in 1918. Of course, there was still the army who kept the country somehow together, and then this was dissolved in the autumn of 1918. At that time I went home to Vienna on the day when the Austrian republic was constituted: 12 December 1918.

What kind of state was musical life in Vienna in after the War?

It took two or three years before everything became workable again. But for an Austrian composer the chief part of his activity was in Germany. Germany had consisted of forty or fifty principalities. Every principality had a duke or king at its head, and as it was the custom at that time he had to have a court theatre, which did opera. So there were fifty permanent operatic theatres in Germany at that time – a tremendous musical activity. Every opera had its orchestra. So there was a kind of musical life which is difficult to imagine knowing the musical life of this country, where nothing similar ever existed.

So the system of court theatres survived the War?

Yes, when the kings and dukes had to go at the end of the World War, the cities or the states took over, because the theatres existed and one couldn’t let them disappear. I became known as an operatic composer just after the First World War – I had my first operatic performance in Breslau in 1919.

Which opera was that?

Der Arzt der Sobeide. It was published at the same time. When an opera was performed, there was no difficulty with the publisher: one knew there would be some response. And this was the case at that time. Two years later came my main operatic success, Die heilige Ente, which had its first performance in Dusseldorf, conducted by George Szell. So my first big steps in publicity came through opera, although, of course, I had written a lot of chamber music at the time, and orchestral music also.

You were also active as a pianist, weren’t you?

Oh yes. I had a good pianistic training. My teacher, Richard Robert [1861–1924], was the teacher of Rudolf Serkin, of Clara Haskil; he was practically the best piano-teacher in Vienna at that time. I came to him when I was about fifteen, and I had a very sound pianistic training, and started teaching, piano first and later composition, because I had to maintain myself.

Were you teaching privately?

Yes. And when in 1909 my teacher Robert became the Director of the New Conservatoire in Vienna , there I taught piano and harmony and counterpoint. I had a full occupation. I don’t think I ever had a time without a full ten hours’ daily work, besides composition.

Did you ever resent teaching for taking time from composition?

No, I couldn’t say that. I accepted things as they came, without asking questions. You mustn’t forget that it was a situation when, with respect to the regular proceedings of the day, one didn’t ask any questions. One accepted things as they were. There were rich and poor, and the poor had to work. I was more or less poor. I had three sisters who too had to work. My sister Erna became a pianist. My other two sisters worked at the office of a bank.

You were composing a lot by this time. Were these commissions, or were you just writing in the hope that someone would come along and perform them?

I couldn’t call them commissions, because ‘commission’ means one pays for something; but if somebody asked me for a composition, I did write it. My first work that was published, Von ewiger Freude, a work for female chorus, organ and harp, was written for an occasion. My teacher Mandyczewski had a female chorus, and there was a performance in the biggest hall in Vienna, the Musikvereinsaal. It was on a poem from the seventeenth century. At time nobody spoke of Baroque poetry, but I found it somewhere in a collection; it appealed to me, and so I wrote music to it. Much later, at least ten years later, there came the fashion for Baroque poetry in Germany, poetry written at the time of the Thirty Years’ War. Any instigation, any claim, was sufficient to make me write music.

You were writing in the Vienna of the ‘Second Viennese School’. How was your music regarded by your contemporaries?

I don’t think I was ever conscious of conforming with anything. I wrote the music that came to me spontaneously. I had made music from my childhood. At that time the chance of listening to music was restricted to public occasions – there was no wireless – so that in a centre of music such as Vienna there were no more than two dozen orchestral concerts throughout the year.

Is that all? We are conventionally told of Vienna in the first thirty years of this century as being alive with music.

It was alive with music. Yet everything was restricted to the comparatively rare chance of public performance. The Philharmonic Orchestra in Vienna gave eight concerts a year. There were two more orchestras, and everyone had, I think, a dozen concerts a year. This was the supply of orchestral music. Chamber music was a rare occasion in public. There was the Rosé Quartet, the members of which were members of the Philharmonic Orchestra; Rosé was its leader. They gave six string quartet recitals throughout the season – not more.

The positive side of this situation was that one studied a score soundly before first hearing it. The only primary possibility of getting acquainted with great music was the piano duet. I had two piano-playing sisters, and we played everything, up to Brahms and Bruckner and Mahler. Every work that was published was first published as a piano duet; it was the way of selling music at the time. One knew music from the inside. Before I went to an orchestral concert, I studied all the scores. I don’t think that a young musician nowadays makes such a sound acquaintance with the score as we did then. Things changed enormously with the advent of radio – it changed the world of music. I had an engagement with the Vienna Radio – it must have been in 1927 or ’28. It was the first time for Vienna Radio that contemporary music was actually performed for a broadcast, and with me on the same occasion was Richard Strauss, who accompanied the singer Steiner in his songs. I played my ‘Heurigen Variations’ on that occasion.

Was there no sense of conflict with more radical composers?

No. These things came later. When broadcasting became such a widely spread activity, there was room for everything in it. Then, in 1929, I became director of the College of Music in Mainz, in West Germany. I was there for three years, until the advent of Hitler, and then I was thrown out. I came back to Vienna in 1933.

You were conducting quite a bit by then, weren’t you?

In Vienna, yes. And then in 1938, when the Nazis came to Vienna, we left instantly and came to this country.

Why Britain?

We intended to go to America. We came to Britain as a first step, because we had friends here. I had invitations to America, several very serious invitations. Now I became acquainted with Tovey, and Tovey invited me to Edinburgh.

How did you meet him?

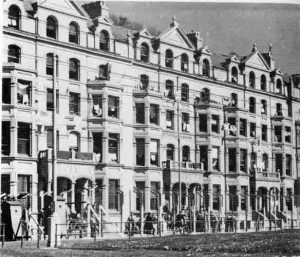

I knew of him, and he knew of me. We met in London. He invited me to Edinburgh because he wanted to bring me to the University. But then the War started, and I was interned as an enemy alien. I spent half a year on the Isle of Man, and then it was too late to go to America during the War.

What were conditions like in the internment camp? I know you wrote music there.

First at Huyton, near Liverpool, and then on the Isle of Man, we organised ourselves as well as possible, and there was music. There was a lot of music. We performed a play to which I wrote the music. One of my compositions there was my Huyton Suite for flute and two violins, for the only musicians who had their instruments with them. It was performed everywhere – in the different tents and houses. It was a curious life. I was interned for five months from May to the end of September. And then I was released because of a skin disease which was very, very torturing and which I kept for many years. Others remained there until the spring of ’41; they were all interned in May 1940. It was a very curious policy, to intern Hitler’s best enemies!

I first came to Edinburgh in April 1938. Tovey invited me to organise the Reid Library, which at that time consisted of cases and boxes full of music and books. I spent the summer of 1938 and the following winter at the Reid Library here, and in the end produced a catalogue of valuable music and books, both manuscript and printed. I had my own system, with the place of the music and a number: the only reasonable way is to place the music according to its size because you cannot do it any differently. I brought things into order. It’s a very valuable library brought together by chance and luck over a long period. There were Reid Professors all through the nineteenth century – good and bad musicians, and no musicians at all; it was a very curious institution. Tovey, of course, was an eminent musician and a splendid spirit. Unfortunately, he fell ill already during that first year of our acquaintance, towards the end of 1938.

He was quite severely rheumatised by then, wasn’t he?

Well, he was catastrophically hit by a sort of deterioration of the whole body. He died during the time when I was on the Isle of Man, in the summer of 1940. But without him we probably would have gone to America before the War. And then it became impossible, and so we remained here after the War, when I became a lecturer at the University. I had been teaching in Edinburgh already during the War. And I was teaching at the University long over my proper age: I was 70 when I retired. Chance decides so many things in life. Chance decided that we remained in Edinburgh.

You were composing all the time?

I have always written music. I have also written several books, but in practice I never wrote a book without a publisher asking for it. It was not my proper vocation, but when I did it, I did it with my fullest interest, and so things came out that have made their way. I wrote in German to begin with. One of my books I translated myself into English, on Schubert, but the others were translated by others. I wrote four monographs – Brahms, Wagner, Schubert and Verdi – and this one here, of Letters of Great Musicians, was republished in German, and more recently also in Spanish, called The Musician’s World. This, too, was based on my experience at the Library. I would never have written it without having a thorough knowledge of the literature. I spent the summer of 1940 at the Reid Library, organising it, but my main activity was reading. All the important sources of music were available there. General Reid was a lover of music, and he founded this library in the early nineteenth century.

You had been widely performed in Germany and Austria before the War.

Oh yes. At the time, before 1933, my operas were performed everywhere. There were so many operatic theatres, as I told you. Three operas of mine came out in the 1920s.

Did you find you had virtually to begin again when you came to Britain?

Yes, it was practically a new start. Again, my chief stimulus was the urge to create. I always wrote music, until at the age of 86 or 88 I closed my workshop and decided: ‘Now it’s enough’. One mustn’t go on beyond a certain age.

Why not?

When one is too old, there are limits. My last work that was published was a set of 24 fugues for piano.

You seem to have been luckier with publishers than with performances.

I was never very active in promoting my own cause, and when came to this country, not far off 50, I was practically unable to do it, so what happened on my behalf happened through friends, through musicians who were interested in my work – through others. I was much too passive to do anything. I always cultivated my piano-playing. I played much in public here too, especially at a time when the Edinburgh lunch-hour concerts were started during the War. It must have been in 1942 or ’43. Tertia Liebental, long forgotten now, was the foundress of these lunch-hour concerts, every Wednesday, and there I played frequently, both as a solo pianist and as a song accompanist or in chamber music. I still play, after four operations each, my hands are still able to play. The operations were for hardening tendons: first the left hand then the right hand. You can see that the surgeon had made much progress between the operations – he learned his job on my hands! I still play as far as I can; as an old man one has one’s limits. But the ear is fine. Fortunately, the ear has hardly deteriorated. It lost a little bit of sharpness of hearing, but no trouble with pitch at all.

I believe you heard Mahler conduct in Vienna.

Yes, it was always an extraordinary experience. I attended one of his earliest performances at the Hofoper. It was Auber’s Fra Diavolo, curiously.

But that was in 1897!

Yes, that is correct. I was only a small boy, but in those days it was the custom for children to go to the opera with their parents, and so we went to see Fra Diavolo. We heard Mahler conduct quite often at the opera house, where he remained until 1907. It is extraordinary how these things stick in the memory. But it was the most marvellous conducting – in all these years I’ve never heard anything to equal it.

You were also acquainted with Franz Schmidt, I believe.

Oh yes. Schmidt was one of the most completely natural musicians I have ever met, an extremely gifted man and very capable indeed. Unfortunately, he had no sense of literary taste and so he chose these atrocious libretti, to which he wrote marvellous music. But he was a profound musician.

And you were a student together with Georg Szell.

‘Student’ only as far as we both had the same teacher, Robert, in Vienna. I was seven years older than he, and he was practically a child when I first met him. He was an enormously mature child. He had started very early; he was splendid at the piano; and he was immensely gifted as a composer. There are two elements the combination of which results in the perfect musician: a perfect ear and a perfect sense of rhythm. Szell had both: physically he was the most perfect musician I have ever met. At the age of sixteen Szell wrote a set of orchestral variations on a theme of his own, which at that time was performed everywhere in Germany. It was a tremendous success. And three years later he wrote his last work. He was never able to work any more. When his sense of self-criticism became awake, composing was something he put aside because it was too much bother. He had never learned to work. His sharpness of musical mind was so enormous that a look into a score was sufficient for him to know everything. So, as a conductor, he hardly had to work: it came to him, so to speak, by itself. And when with this sharpening self-criticism composing became something difficult, he just put it aside; he didn’t do it any more.

Have you found composing difficult at any point in your career, patches when nothing seems to come?

For me the process of composition was always concentration to the utmost, and to every detail. I never put something on paper without being sure of its necessity. During many, many years in this country during the latest 20 or 25 years of my life as a composer, I mainly wrote chamber music. It was because of the intimacy and the feeling of being perfectly in balance with myself. I can’t express it in any different way. So, besides the Huyton Suite for flute and two violins, I wrote a Trio for oboe, violin and cello – the most transparent sound, where every note is so essential that one couldn’t do without it. Anyway, I had the chance of having so much music published – more than a hundred works. The earlier ones, many of them, are out of print, and many not republished so far. Publishers, too, have their interests to think of, and so music goes out of commission. But I have had works published by more than a dozen publishers. My operas, of course, were published: they couldn’t have been performed without that.

Do you ever feel resentful that so little of it gets heard nowadays?

This is regrettable. But I am confident of not having published anything about which I could say that I was sorry to have done it. So far I have a good conscience.

Do you ever look back and say of your music: ‘Ah, I must have been listening to Reger, say, or Brahms’?

No, as to the identity of my music, I have always remained self-confident!