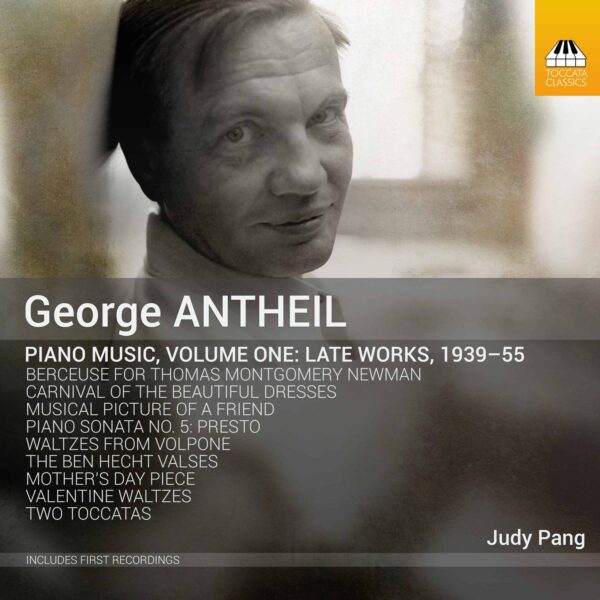

Reading Martin Anderson’s ‘modest memories’ of André Previn brought to mind that, during my millennial research on George Antheil (bearing fruit, among other places, in Toccata Classics TOCC0447), I was able to contact Previn through someone at Schirmer. I knew Antheil had admired his young colleague, and so I was full of expectations. The answer, through Mrs Peggy Monastra, was that André ‘laughed and explained that they only met once, briefly, backstage after a concert. He said he told Antheil how much he admired his 5th Symphony and said GA seemed surprised that Previn knew it at all. He said that was really the extent of their conversation and the only time they ever met’. And that was that.

But, wait, why did he laugh? Was it that he knew more? Memories of my missed interview with Elmer Bernstein haunted me: I had written to his secretary and, unexpectedly, she answered to ask if I was ready for an interview that same afternoon. Actually, I wasn’t. I was young and inexperienced, and had no tape recorder to connect with that thing… what was it called? oh, yes, a telephone! And so I responded feebly: ‘Can I write back to you in a few days?’ When I did, it was too late – Bernstein had embarked in a new soundtrack to be composed urgently. Would I wait that it was finished? Soon afterwards I opened the newspaper and read of his sudden death. He had, said his secretary, many anecdotes to relate, and knew much of Antheil’s peccadillos. So now, if there were a medium who could help me, Mr Bernstein would be the first name I would invoke. And already knowing something of Antheil’s sex life, I would have given just about anything to know more. Once, for example, I had been told of a door opened by mistake in a hotel room in Madrid, where Ava Gardner was not with Frank Sinatra. And Hans Heinz Stuckenschmidt, the German critic who visited the States in 1949, saw Antheil indicate a villa in Beverly Hills and confess with elegant nonchalance: ‘That’s the house where I faaked Hedy Lamarr’.

I am not interested only in such secrets, of course, but that itch about any idol is ever-present, and, since Antheil had died in 1959, most of the people who knew him and were still alive in the last twenty years were either composition pupils or young actresses and showgirls. And both categories do not like to tell you everything – the composers because they want you to ask about their own music, and the old ladies because they suspect you want to know only that.

But I was lucky in many instances, and historical research can sometimes make you really dizzy (although my Swiss wife objects that research is not a job but a hobby, since the money that goes out is much more than the money that comes in). It hasn’t yet happened that an old lady has opened her closet, whispering: ‘Early scores? Yes, I should have some autograph symphony here…’. But I once contacted Brent Monahan, a tenor and the last pupil of a singing teacher in Trenton, New Jersey (Antheil’s birthplace). His teacher had passed away at 98, leaving his papers to Monahan, and there were three early songs by Antheil among them. One was even in German, Antheil’s mother tongue before the First World War, and so probably the work of a fourteen-year-old budding composer. Were the songs still in his possession, I asked. Yes. He had offered them to a major New York University, and they had accepted them, provided that Mr Monahan paid the cost of sending them! And that is why I have them now in my own possession.

Sometimes, however, the only clue I have is a wild-goose chase, as it was with the cellist Steven Isserlis, whose grandmother, according to a nonagenarian pianist I knew, was the dedicatee of an Antheil symphony. Contacted by e-mail, poor Steven could only wish me good luck with my detective work.

In any case, among my successes I can number a 95-year-old lady in Trenton, daughter of Gustav Hagedorn, violist and local conductor, who could remember when she had come downstairs shouting to stop that bedlam, as she could not sleep. Antheil was banging on the piano, and Elizabeth was seven years old, and so it was 1922! I felt as the spectator of that early footage showing the Moscow Army parade in 1895 (if I remember correctly), where the centenarian veterans of the Borodino battle were slowly passing by.. a moving (sic) image of people born in the eighteenth cetury, and who had seen Napoleon (from afar, I imagine!)

I felt the same dizziness when Henry Brant, on the phone from Santa Barbara, California, told me about his meeting with his future teacher Antheil in 1932 (Copland was not the right one for him, he said). At the time of that interview, 1997, my English was so inadequate that I understood half of what I was being told, so much so that I simply went on nodding vocally with my ‘oh.. ah… oh.. really?’ (while I was wondering what the heck meant this or that word). When Brant asked me if I wanted to know more of an anecdote, I did not even gather the question mark and went on with my ‘Oh, really?’

Old age, of course, does not help (I do not mean mine). When I interviewed Werner Gebauer, who was first violin of the Dallas Symphony under Doráti and who had premiered Antheil’s Violin Concerto there in 1946, his health was so bad that most of what he said went lost among the frequent coughing. But sure I got the name of Hitler, to whom young Gebauer in Berlin had played Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto! And when I asked him about Hedy Lamarr, whom I imagined he had met at the Antheil household in Hollywood, he said: ‘Yes, of course I knew her, we met in some theatre in Vienna, in 1933!’

A baritone in New York narrated of the premiere of Antheil’s Helen Retires, his second opera, at the Juilliard School, where he was a student, in 1934. I remember that interview, however, mostly because the old man sat in night-gown on his sofa, but had evidently forgotten to wear his underwear. I suppose that was my nemesis, as I had too much investigated in the others’ underwear (figuratively speaking).

Of course, some historical documents and testimonies aren’t quite what they could have been, as you’ll know if you’ve heard the Edison wax roll (1890) with Tchaikovsky’s and Anton Rubinstein’s voices. A soprano sings. Tchaikovsky: ‘This trill could be better!’ Even worse with Rubinstein, whose elaborate answer to an invitation to play for posterity was: ‘No’.

In other cases, old age plays its tricks: Brant recalled playing Antheil’s Ballet mécanique four hands with its composer at the screening with Léger’s movie, at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1935 – whereas it was actually done on a player piano, and they were playing Satie’s Relâche instead. And sometimes you have the unbearable impression that you know more than your source. Not to mention the frustration of understanding that the person you are looking at got life in the wrong way, and suspiciously stares at you as if you were a killer, or starts accusing people of having stolen ‘my ideas’ and well-deserved success in whatever artistic field he or she was in.

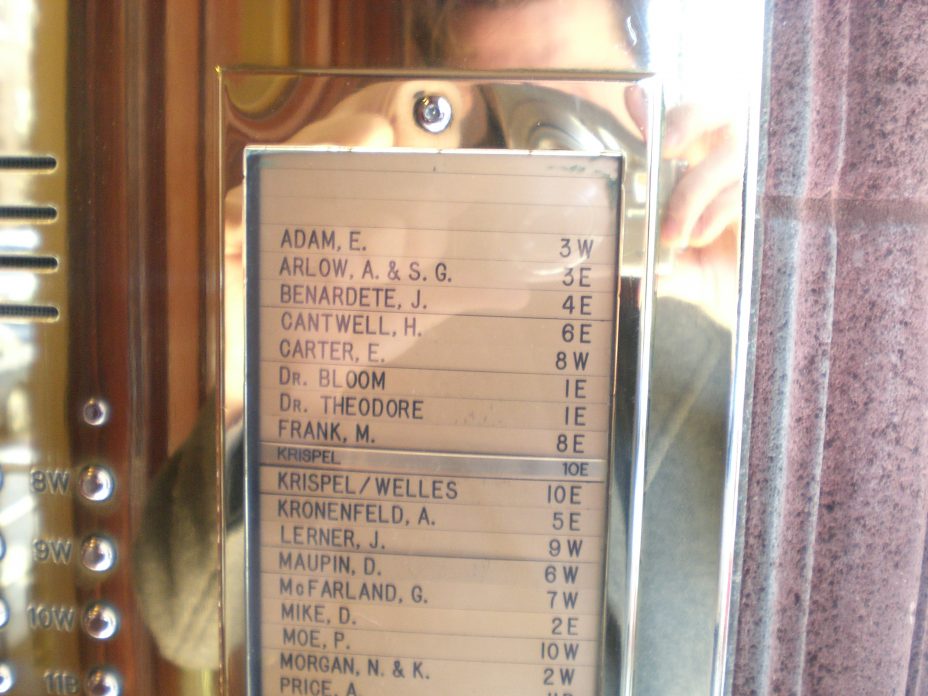

Sometimes, too, a mixture of modesty and realism holds you back. When I was in front of Elliott Carter’s apartment in lower Manhattan and I found his doorbell, I shuddered – why should I announce myself to such a mythical figure, who took over Antheil’s apartment and Steinway in New York, when Antheil left for Hollywood in 1936? He did not even like the man, and less so his music! I desisted: why bother him at 98, when he was probably composing one of his very intricate scores, and what for – to take a picture with him and live on second-hand glory? I went on my way.

But if you are hoping to hear the secret of a long life from a centenarian, the answer could come from Leo Ornstein, who confided to me before his death at the age of 107: ‘Eat oatmeal every morning!’