There are always some coincidences when the significant events of history happen. Most people can probably remember the moment when they heard the news of the attack on the Twin Towers. More recently we can perhaps pinpoint when and where we contracted COVID-19, or what we were doing on the day when Russia invaded Ukraine.

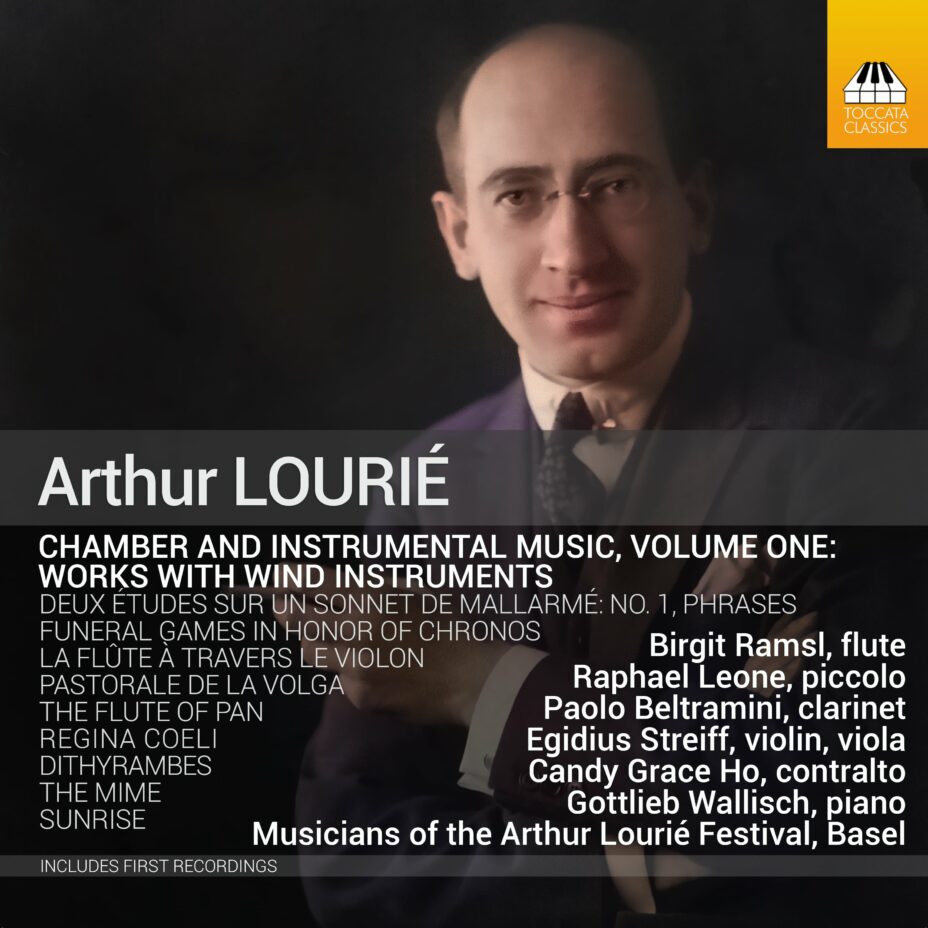

In my capacity as the producer of Arthur Lourié’s chamber and instrumental music on Toccata Classics TOCC 0652, on 24 February 2022 I was with the flautists Lucie Brotbek Prochaskova and Birgit Ramsl, the piccolo player Raphael Leone, the pianist Gottlieb Wallisch and the percussionist Nicolas Suter and we were in Zurich recording Lourié’s enigmatic Funeral Games in Honor of Chronos. The circumstances were not particularly auspicious: it was intensely cold, there was the difficulty of all playing together when extreme precautions were in place to avoid COVID contagion and during the recording one of the two flute-players had a sudden nosebleed. We had to stop recording for an hour while waiting for a doctor. Having safely finished our recording, we heard the news about the outbreak of the war.

The coincidence lies in the fact that the piece in question is really a dramatic lament for the loss of some of Lourié’s associates. Funeral Games had been started around 1941 when Lourié lost his friend, the erudite Abbé Roger Bréchard, who died on the battlefield on 20 June 1940 during the Nazi invasion of France. Bréchard, who had baptised the novelist Irène Némirovsky, was a friend of the Catholic philosopher Jacques Maritain, and was only the first in a series of friends and acquaintances whom Lourié mourned. In fact, the gestation of Funeral Games did not end until January 1964, by which time Lourié himself was a survivor of a lost era. As Samuel Zinsli aptly writes in the booklet for this album, ‘Perhaps the piece can be seen in context with a series of memoirs he published in Russian emigration journals in the USA in the 1960s in which he spoke about the guiding stars of his St Petersburg youth: Kuzmin, Blok, Khlebnikov, Mayakovsky, Glebova-Sudeikina and Osip Mandelstam, among others, all dead by then’.

Throughout a life as a migrant, impelled by political differences, economic hardships, wars, and even espionage and delations, Arthur Lourié, a Belarusian Jew who converted to Catholicism, could call himself, at the end of his life, a true survivor. After fleeing post-revolutionary Russia, where he had held prominent positions, Lourié would never hear from his family again. And the Silver Age of Moscow and St Petersburg was left with only bewildered émigrés in France and the United States, including himself.

On that unpropitious day in February 2022 when we recorded Lourié’s dirge for an artistic era that had contributed so much to world culture, I remembered a verse of the ‘epitaph’ from Job that he had placed before the music: (28:3) 5: ‘Terra, de qua oriebatur panis, in loco suo igni subversa est’ (‘The land, out of which bread grew in its place, hath been overturned with fire’).