Time for a little controversy on this blog – but that’s not my aim, which is to try to understand why, when there are so many outstanding female performing artists (and so ‘music’ itself is not at issue), are there still so few female composers. I think I may have an explanation – and hear me out before you hit the ceiling!

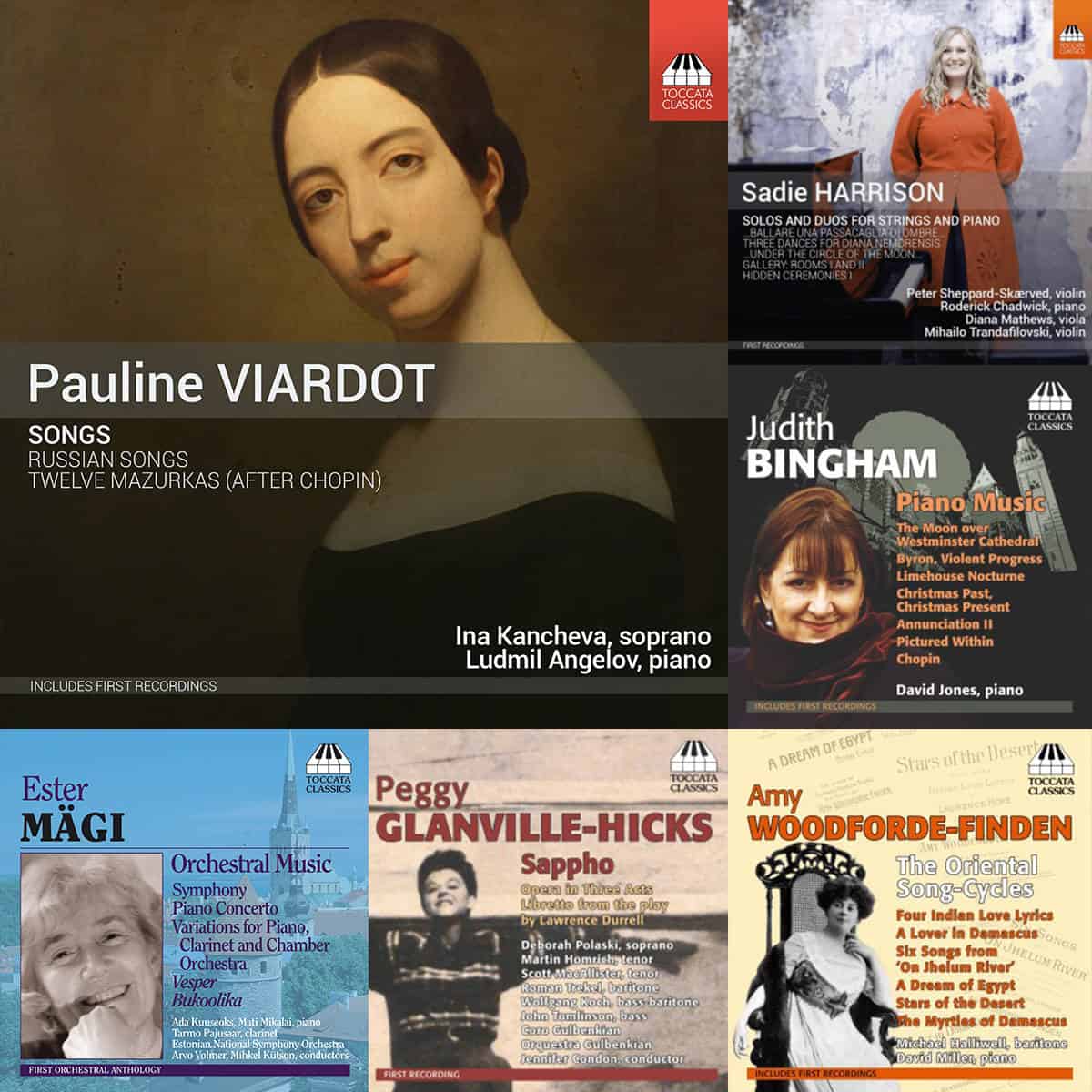

One of the first Toccata Classics releases of the year features fifteen Russian songs and twelve arrangements of Chopin mazurkas by Pauline Viardot (1821–1910), who seems to have held all the brilliant (male!) minds of nineteenth-century Europe in her thrall. She was a friend of Berlioz, Chopin, Clara Schumann, George Sand, Turgenev (who was probably also her lover) and many other artists, writers and musicians. She rubbed shoulders with Brahms (she premiered the Alto Rhapsody), Debussy, Liszt, Glinka, Gounod, Mendelssohn, Anton Rubinstein and even Stravinsky. Schumann’s Liederkreis, Op. 24, is one of many compositions dedicated to her. She was fluent in Spanish, Italian, French and English by the age of four, adding other languages later. She studied composition with Reicha and piano with Liszt, and despite her later fame as a singer made her concert debut as a pianist. Saint-Saëns explained something of her impact: ‘Mme Viardot was not beautiful: she was worse. The portrait painted of her by Ary Scheffer [it’s on the front of the Toccata Classics disc] is the only one that captures the look of this unique woman and gives an idea of her strange, powerful fascination. What made her particularly captivating, even more than her singing talent, was her character – certainly one of the most astonishing I have come across’.

Her compositions were much admired by her contemporaries, but only a handful of songs and instrumental pieces seem ever to have been recorded – the Russian songs that Ina Kancheva and Ludmil Angelov perform in our new release have not been before the microphone before. And yet her worklist contains over a hundred songs, set to French, German, Italian, Spanish, and Russian texts, pieces for piano and violin and six operettas and light stage-works, three of them to libretti by Turgenev. They were performed in Viardot’s home theatre, for which an unusual admission price was charged: a potato, and so the theatre became known among her friends as the Théâtre des pommes de terre. The evidence of ‘our’ songs suggests that these stage-works would reward the inquisitive impresario, but as far as I’m aware none has been performed, let alone produced, for a very long time.

Does this apparent lack of interest come about because the woman composer – and conductor, come to that – is still regarded as something of an oddity, no matter how much we may protest that we have banished the prejudices of earlier times? Toccata Classics has released several recordings of women composers: orchestral music by Ester Mägi (who was 94 on 10 January), piano music by my former neighbour Judith Bingham, the opera Sappho by Peggy Glanville-Hicks, song-cycles by Amy Woodforde-Finden and, most recently, instrumental and chamber music by Sadie Harrison. Now, even though we have plans for more music by Sadie Harrison and other female composers, our track record isn’t much better than anyone else’s. The old preconceptions that put an end to the composing career of Clara Schumann (for instance) have largely evaporated, and there seem to be more good female composers at work today than ever before – but composers still seem to be predominantly male. So is there a different explanation than social pressure or convention? I think there is, and my hunch is that it’s a physiological one.

It strikes me that what gives a composer the tenacity to sit at a desk endlessly turning patterns over in his (or her!) mind is likely to be some form of autism – which is a spectral condition, so that you have it to varying degrees of intensity. Some composers would seem to have been full-blown Asperger sufferers and so to have had the social dysfunctionality that goes with it – think of Alkan, Beethoven, Brahms, Janáček, Langgaard, Martinů, Prokofiev, Shostakovich, Stravinsky, Weinberg and many others. My suspicion, indeed, is that the capacity to take infinite pains over something that’s often minutious means that music, mathematics and other such ‘mental’ disciplines are going to attract and reward minds that are autistic to some degree and find satisfaction in such activity.

Now, autism affects males much more than females, to an extent current estimates of which vary, but the ranges are between twice and sixteen times as much. Since the historical preponderance of male over female composers seems to have survived into our more liberal times, could it be that there are fewer composing women simply because women as a rule are more ‘normal’ than men, that fewer of them are obsessive to the degree required to be a Janáček or a Shostakovich? Lucky them, indeed: Janáček never enjoyed a natural, relaxed loving human relationship in his life, and Shostakovich was crippled by shyness all his. That kind of creativity is a double-edged sword: we listeners benefit from outstanding music, but its creators did not always know the simple human networks that we take for granted.

I bounced my idea that autism may be a linking factor in the lives of the major composers off Simon Baron-Cohen, Professor of Developmental Psychopathology at the University of Cambridge and Director of the Autism Research Centre there and he thought it might have some merit. When I’ve mentioned it in conversation, I find that people tend to try to defend their favoured composer, but there’s no value-judgement being made here. Indeed, if you bear in mind that Prokofiev (for example) might have had Aspergers, it makes his famously abrupt manner much easier to understand, and accept; he becomes a victim rather than a transgressor.

And is there then anything to the possibility that autism might explain the preponderance of male composers? I might lose some friends, male and female, by saying that, on balance, the women composers I know are a good deal less driven, better balanced, than the men – who would, I think, admit it freely. I’m an individualist, and I’m naturally uncomfortable thinking of other individuals in collective terms. But I wonder if I might have come across something here – and what’s so wrong with being normal, anyway?

In the middle of the C20 there was a number of very fine British women composers: Elizabeth Maconchy, Grace Williams, Ruth Gipps and Doreen Carwithen.

Of these Maconchy and Carwithen have had a number of CDs dedicated to their music, but Grace Williams still needs her Symphony No.1, her Violin Concerto and her Sinfonia Concertante for Piano and Orchestra recorded, and Ruth Gipps still needs her Symphonies 1, 3, 4, 5 and other works recorded.

Toccata Classics would love to be able to record the works you mention and more — it’s just a question of ££££. We tried to get a recording of Grace Williams songs moving a few years ago but were met with complete indifference from the members of the Welsh Assembly to whom we wrote.

On an Amazon discussion forum about women composers, I made a reference to work done by a (female) scientist about this feature of creativity i.e. that men were – as a population – less gathered around a norm than women. So that while there may be many more geniuses, there were also many more dull and psychologically damaged.

Unfortunately I got roundly attacked for sexism without any attempt by anyone else to grapple with the evidence or to distinguish between individuals and populations.

I’d also point to the disproportionate number of successful homosexual composers, also allowed to concentrate on their work without the distractions of raising a family.

Of course I don’t believe that these innate qualities are the sole reason for the preponderance continuing, but they do deserve consideration. In modern times, I would suggest that many women have chosen other musical channels to shine in, a combination of opportunity and possibly being less attracted to the more academic strains of music that an Aspergerish mind might delight in.

Finally, can I make an appeal for a recording of the lovely Peggy Glanville-Hicks Viola Concerto?

What you write strikes me as eminently sensible. A lot of people hear such arguments and react emotionally — either defensively or aggressively — without realising that there are no value-judgements involved.

PGH Viola Concerto: thanks for the tip.

Hi Martin, that’s a fascinating idea. Years ago I heard a lecture by Joachim Thalmann, professor at Detmold music university, on artists suffering of Asperger (particularly Glenn Gould and Klaus Kinski), which made me think about very much. You might want to contact him, he’s among my FB friends.

Best wishes from Berlin,

Wendelin

Thanks for that — I’ll chase it up.

Martin, Interesting theory, but I must admit that having just had my opera “Cold Mountain” premiered in a sold-out run in Santa Fe, and then performed to completely full houses here in Philadelphia, and having spent 28 months writing such a large work, I can safely say I don’t fit in the Autism spectrum. I’ve completed 10 works since finishing the opera in 2014, and am extremely busy with commissions, and have 60 some odd recordings out, so I’m answering from the “inside” of your question. I am frequently in public situations where I interact with the performers and audiences, and I might not be able to do that if I was on the Autism spectrum. What has made my career and success possible is the fact that people have given me chances and I’ve done my best to work hard in making the most of those chances. Thanks for listening.

Hang on, Jennifer (hello again after a long time, BTW): I didn’t say that all composers were autistic. I just wondered whether autism, a predominantly male condition, might have some explanatory role in the preponderance of men among composers — that’s all!

The author seems to disregard the still prevalent division of societally-enforced roles between men an women, i.e., men, for the most part CAN spend obsessive hours creating and composing because women, again for the most part, are taking care of thr children, the shopping, the cooking, the cleaning, and all other tasks that afford men the clean, quiet, well-lightef space necessary for creation. Why is it so easy for men to overlook this point? As for speculation about autism being mostly male, I also wonder whether the truth is that women’s presenting symptoms are different due to gender socialization, and have just not been recognized.

I don’t doubt for a minute that there are socially enforced roles at work here — but don’t you think it’s telling that the weakening of sexual stereotypes and pressures over (say) the past century hasn’t produced an increase in the (relative) numbers of female composers?

As for the diagnosis of autumn being thwarted by the presentation of different symptoms, I think you rather insult the neuroscientists here! I have seen anyone else claim that the argument for autism being predominantly a male trait was speculative — the scientific opinion seems fairly settled on that.

Hi Martin. I have to admire your pluck in bringing up this topic. It is usually not considered politically correct to describe any gender differences that go beyond reproductive issues; all differences in accomplishments in employment outside the home are due to patriarchal suppression. Women, given a break from domestic and child-raising responsibilities, will accomplish exactly what men do 50-50. To this you cannily reply, that some male accomplishments may be due to their being subject to neurological/developmental conditions. Therefore, females are too healthy to be great. That’s almost parodistically a simplification of your argument. I worry that given the emotional stakes, can we even research this? Can there be any studies that question the politically correct point of view? The former president of Harvard Lawrence Summers was highly criticized for suggesting this. You are quite correct that the statistics do show a preponderance of males with autism and, given how early this is manifested (even likely in utero) no one would plausibly claim that this is a socialization process. I have a particular love of music and composers as well as a son with severe autism who just had his 36th birthday yesterday. (He was autistic before it was popular to be autistic. We even wrote a children’s book on this.) As a physician I also like to think I have a love of science. Frankly, I’m not sure that any research should cause any clear thinking person to say that women (or men) shouldn’t have every opportunity to succeed in every field. A statistically significant trend toward accomplishments segregated by gender doesn’t mean that any particular person can’t achieve greatness. (Not **all** people with autism are male.) The contentious issue is whether the fact of intersexual disparities in accomplishments is *only* due to the patriarchal attitudes/stereotypical sex roles. I have my doubts. Even in the patriarchal societies in which women have struggled, women have always excelled in novel writing and instrumental performance. That said, as a listener all this is irrelevant. I want to hear more music by women, and have enjoyed and admired much of what I have already heard. As well, I have already made efforts behind the scenes to try to get their works performed

I can’t respond as eloquently as most previous commenters here, but yours is certainly an interesting idea.

My tendency would be to come from a different tack, however, which mixes themes from genetics/psychology/physiology and sociology (not that I know a lot about any of them!). Rather than looking at ‘male composers’ or ‘female composers’, perhaps we should look at the bigger picture and think of ‘male’ and ‘female’ – the old Mars/Venus concept.

Firstly, maybe there are, historically, far more male than female composers because of equality of opportunity. I don’t know how relevant this is in our day and age, but it may still have a knock-on effect. Taking a cursory look at conservatoire enrolment records up until the early-mid 1900s, for example, is likely to throw up far more male than female names (I would guess). If the desire to become a musician (pianist, organist, conductor, orchestral player, etc, as well as composer) was entertained and nurtured (if it even got to that stage), wouldn’t it have more likely been men who would have followed that career choice than women? It’s only relatively recently that women have had anything like the aforementioned equality of opportunity to pursue their desired careers, previously having had the ‘role’ of primary home-maker and care-giver in the family setting – leaving no time to pursue a career as a composer. Many successful female pianists of the nineteenth century, for example, would have traded in their concertising lives for ‘marital bliss’ because of society’s expectations of them.

Of course I’m making a generalisation in this point – I’m sure there have been exceptions to this.

Secondly, and it’s nothing new, is to say that men and women are simply wired differently – they way they think especially. Because men tend to comparmentalise their thoughts/feelings/processes, it seems (to me) to make sense that more men are composers, because they ‘compartmentalise’ their lives in a similar way. Composing is a compartment of their lives that they can wholly focus on without the distraction of other elements of their lives – perhaps in an unbalanced way and helping to explain your autistic spectrum argument. Whereas, because women tend to have a more complicated thought process than men, it leads me to suspect that the level of focus a man lends to his music-making is not as easily measured in women. Perhaps they are not as obsessive because their thought processes don’t allow them to become so, and because of the demands put on their thought processes from other areas of their lives ?

Mixing my two points together (not very coherently I must confess), one could argue that composition, although leading to an emotional response from an audience, is a process, which is something to which a compartmentalising mind would be attracted. And we know that ‘being a musician’ was sometimes frowned on in earlier times, because of its association with emotions and because it was deemed an unreliable profession. Is it true to suggest, then, that composing or being a composer was a safe way of compartmentalising your emotions and thoughts in a form acceptable to a male-dominated society?

Autism is a condition that runs in my family. I know I can be a little obsessive about things, and when I was studying composition as part of my music degree, I often agonised over what notes to use and how they should fit together (just for starters!), meaning that composition was a pain-staking process for me, one that I was ultimately not ready for, so I don’t know if my thoughts above have any weight.

But there you go!

Hi Martin,

To start a meaningful discussion how useful (or not) are psychiatric labels when it comes to creativity, I highly recommend this award winning review of Rybka’s book on Martinu by Dr. Erik Entwistle: http://erikentwistle.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/Entwistle-Review-of-Martinu-Book1.pdf

For anyone interested in exploring the “woman composer question” seriously, I recommend these articles by Dr. Eugene Gates: “Women composers. A critical review of the psychological literature” and “The woman composer question: Philosophical and historical perspectives”.

These and other articles on women in music can downloaded free from

http://www.kapralova.org/JOURNAL.htm

On another note, I was happy to see that Toccata Press has released a few discs with music by several women composers. Magi’s orchestral CD was a revelation for me, personally. Keep up the good work!

Cheers,

Karla

I read that review when it first appeared. Unfortunately, I don’t think Entwistle unmakes Rybka’s argument any more effectively that Rybka makes it in the first place. Entwistle objects to the basic argument thus: “How then are we are to understand other highly prolific composers such as Mozart or Milhaud? Must they too be pathologized in order to be understood?” No, not necessarily pathologised, but you don’t have to count very far to realise that there is here a phenomenon which has not yet been adequately explained. Using emotive language like “pathologize” invites a kind of oh-no response, but how then indeed are we to understand composers like Mozart and Milhaud? There’s no value-judgement involved in stating the obvious fact that these were not ordinary men.