One of my favorite things to do is go into libraries, find my way to the orchestral scores and lose myself in there for untold lengths of time. I’ve discovered so many things just by seeing “what’s there”. When I was a graduate conducting student at Indiana University, I spent far too many hours in their library when I should been studying. As Associate Professor and orchestra conductor at Azusa Pacific University (APU) in Southern California, I’ve certainly gone through their library to check out what’s on the shelves. One of the collection of scores they have is a set called “Recent Discoveries in American Music”. This is a series of works consisting of music from the 19th and early 20th century that, in most cases, were previously unpublished. One score that caught my eye a few years ago was one that said “Leopold Damrosch: Symphony in A” on its spine. I had heard of Damrosch and his famous children but had no idea that he composed, let alone had written a symphony. Thumbing through the score, I could see many fascinating things in it. But, like so many other pieces, I had to file it away in brain for the future. There was something alluring about this work though.

While I love conducting the standard repertoire as much as any other conductor, I do have a penchant for performing unusual repertoire. There is so much great music out there that is never played. In the last few years, I conducted the first complete performance in the US of a symphony by Denmark’s Rued Langaard, led the first US west coast performance ever of a symphony by Sweden’s Allan Pettersson and did the first US performance in over 60 years of Martinu’s charming Intermezzo for Orchestra. One of the things I’m grateful for at APU is that it’s perfectly OK for me to perform some of these obscure works.

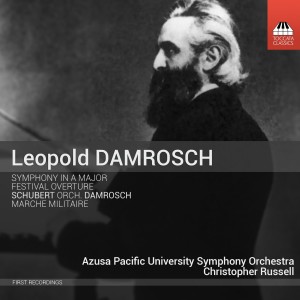

When I started speaking to Toccata Classics President Martin Anderson about a project, we threw around several ideas. I was pleased though that he went with my idea to do an all-Damrosch disc without ever having heard a note of his music. Last fall, as a trial run, we performed Damrosch’s Fest Overture. I’m not sure the last time this work was ever played because we could not find the parts and had to create them from the full score. The work is a 12-minute full-blooded Wagnerian overture. I like to call it “Wagner on steroids”. After Martin heard it, we decided to go ahead with recording the Symphony and his charming orchestration of Marche Militaire. This was a wonderful opportunity to bring a new appreciation to previously-forgotten music by a unique figure in music history.

This Symphony was uncharted territory as there was not only no recording but the work had never been performed at all. This gave the project a bigger sense of excitement knowing that we would bring a long-silent work to life. In this age, we are so used to having just about every piece of music ever written available in some sort of format. Here though the APU Symphony and I were faced with a 45-minute work from 1873 with no aural recording of it. And having no previous recording was liberating: we were the trendsetters.

Fortunately, the score came with many notes from editor Kati Agocs. This helped me understand more about Damrosch, the work, its construction and place in history. Digging into the Symphony, one of the big challenges was figuring out appropriate tempi. Sometimes what I was able to play on the piano sounded wrong when I tried that same tempo with the orchestra so it was a constant adjusting, something obviously not done in work more well known. Damrosch also uses some unusual harmonies and harmonic progression, not unlike Wagner but certainly more unpredictable. In the Fest Overture, there is brass chorale that has the first two chords moving a tritone apart. It took me a long time to realize that that was correct.

I’m happy that my orchestra at APU is used to me throwing odd things at them. So, in some ways, this was “just another thing” but doing something as massive and unknown as the Symphony was a different challenge altogether. While the parts for the Symphony were very nicely prepared, just playing what was on the page was not enough. Through rehearsals, I had to show them what connected to what, where the important lines were and weren’t and what the general spirit should be. After a while, the secrets of the Symphony revealed themselves to all. In the end, I was very pleased with their performance and dedication to this project.

I’m happy that my orchestra at APU is used to me throwing odd things at them. So, in some ways, this was “just another thing” but doing something as massive and unknown as the Symphony was a different challenge altogether. While the parts for the Symphony were very nicely prepared, just playing what was on the page was not enough. Through rehearsals, I had to show them what connected to what, where the important lines were and weren’t and what the general spirit should be. After a while, the secrets of the Symphony revealed themselves to all. In the end, I was very pleased with their performance and dedication to this project.

Damrosch’s Symphony is both conventional and unusual. It is in the traditional four movements with the scherzo second. The first movement is basically in sonata form with a few detours towards the end. The second movement is a tiny rustic-like dance. The third movement is by far the longest with a giant funeral march framing a wild fugue section. The finale is the most conventional, written in sonata form with a faster coda. Damrosch uses both traditional themes and Wagneresque leitmotifs that return later in the work. The overall effect is one of power, humor, charm, tenderness and poignancy all in one. It is not unlike Mahler saying that a symphony should “embrace the world”.

Dear Professor Russell,

As a descendant of Leopold Damrosch I am quite excited that you discovered and have actually played and recorded some of his music. I have ordered the CD and can’t wait to get it.

I would love to connect with you and hear more about your discovery and development of this music. I have a son who lives in Brea and one in Temecula so am on the west coast a couple of times a year.

Please let me know if you would be open to this. My email is wsleeper@aol.com

All the best!

William (Bill) Damrosch Sleeper