I met Ronald only once. I simply came to his music too late in his life — which came to a peaceful end on 28 March. It was listening to a student at Trinity Laban Conservatoire of Music and Dance play his piano transcription of Wiegenlied aus Wozzeck that made me realise, in a moment of epiphany, that I simply must know his œuvre, and perhaps even meet this great man.

Actually, it nearly happened twice. In spring 2008 I was a third-year undergraduate student of the Royal College of Music, and was frantically trying to keep on top of my dissertation on ‘The Pianistic Technique of Ferruccio Busoni’. Someone said to me at this time that Ronald Stevenson was a leading authority on Busoni, and suggested I try and get in touch with him to see what else I could learn. I wrote to Ronald – and, two weeks later, had a specimen of some of the most famous handwriting in music land on my doormat. In his letter was an apology for not replying sooner: he had just had a ‘premiere’ – I’m guessing Ben Dorain – in Glasgow, and had been busy with subsequent correspondence.

I telephoned some days later and was greeted by the kindly voice of Marjorie, Ronald’s wife of six decades. After chatting for a while she handed me over to Ronald himself and felt arrested by this phlegmatic personality talking very briskly and concisely down the phone to me. We had a pleasant conversation and agreed to meet at their home one day in May, and left it there. As chance had it, I got through to the final of a competition at the RCM which took place on that very day, so the visit was postponed.

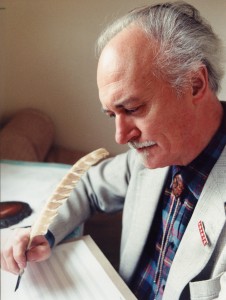

Ronald Stevenson composing, quill in hand, at the desk in his ‘Den of Musiquity’ at home in the village of West Linton below Edinburgh

Five years passed, and in August 2013 I finally set foot in Townfoot House, West Linton, Peebleshire. I remember wandering down the hill from the main road where the coach from Edinburgh dropped me. Marjorie was chatting to a neighbour outside, and obviously wondering where I’d got to as I was (predictably) a bit late for having initially wandered in the wrong direction. She spotted me, and ushered me inside this handsome old house with the big blue door, the home of the Stevensons since 1955. As I turned round to enter their cosy living room, I spotted Ronald himself quietly pottering in his study. He greeted me with a warm smile and a handshake that somehow conveyed enormous gratitude that a young musician should want to meet him. Considering what a giant figure he remains in the world of music through his remarkable achievements, there was an almost overwhelming sense of humility which he exuded, and a deep humanity. I stayed at Townfoot House for five hours that day and only left because I had to catch a train.

In the course of that afternoon I had the immense privilege of seeing some of Ronald’s collection of documents and other items that are inestimably significant for musical history. He possesses Ferruccio Busoni’s piano bench (Ronald was perhaps the authority on Busoni), plus many other things given to him by Gerda Busoni, the composer’s widow. He talked to me about his correspondence with Shostakovich, Britten and even Sibelius. (The latter, literally, made my jaw drop. He wrote a prelude in 1947, aged nineteen, in homage to Sibelius, sent it to him, and Sibelius wrote back expressing gratitude and saying that he liked the piece. It’s a great little story but the point, really, is that in our midst was what many before me have already said: a living link to a lost generation of musicians’. Many of his letters are now held in the National Library of Scotland.

That day we talked about not only Ronald’s own music but that of others – especially composers who have never quite entered mainstream musical consciousness. He and Marjorie persuaded me to take an interest in the compositional theories of Bernhard Ziehn, and introduced me to the Swiss-Polish composer Czesław Marek. They kindly gave me one of Ronald’s CDs of him playing Marek’s Tryptichon. It is a deeply poignant piece; I won’t forget the way Marjorie was in raptures, visibly moved to tears during its ‘Fantasia’, as they played the CD for me in their living room.

Ronald’s attitude to concert-programming was interesting, too. His extant but lamentably rare commercial recordings demonstrate colourful programming, revealing gems of the repertoire not commonly known about (or, perhaps, those which are not in fashion – Ronald did not give a fig for ‘fashion’ in music and I believe he is quoted somewhere as saying that).

And of course, he played a little bit for me – a gorgeous little piece he wrote as a young man for Marjorie when they were courting. It was a rare chance, in the 21st century, to experience the pianism of a twentieth-century great, at close hand. His was the pianism of the nineteenth century…. But one can read as much as one likes elsewhere on this.

Ronald is the composer whose music, for me, most convincingly assimilates the Scottish vernacular with an aesthetic of nineteeth-century pianism. The latter is extended by his own progressive ideas (derived from the likes of Ziehn) on the direction of contemporary music. There is the influence of Busoni’s explorations of the greater potential of tonality, and the will to discover and utilise new scales. Ronald’s aesthetic explorations are demonstrated and summarised in his 20th Century Music Diary, a collection of short compositional studies. This is what he considered to be his most important work from his early period, up to the late 1950s. His Scottish Folk Music Settings for piano are in the manner of Percy Grainger, whose correspondence with Ronald is published by Toccata Press as Comrades in Art. Many, of course, know Stevenson’s name for his 80-minute Passacaglia on DSCH, but also for his piano transcriptions of Bach, Gershwin, Liszt… you name who else. Those he created of Eugene Ysaÿe’s solo-violin sonatas are the finest examples of their kind that I know of; nowhere else are there more convincing transcriptions of works originally for a solo linear instrument. Ronald himself believed they ranked among his greatest artistic achievements. Audacious a statement as this may seem, I believe his achievement here may eclipse that of Busoni’s ‘Chaconne’.

Some time later, I decided it was imperative that Ronald’s unrecorded piano music became recorded. I emailed Martin Anderson, for whom I’d previously recorded Ronald Center’s music, and suggested I begin with a disc of Scottish-themed music. Marjorie kindly let me have some of the scores, and I read through them. It was beautiful, all of it. The Scottish Folk Music Settings for Piano are a joy to play, with gorgeous harmonies. It is amazing that one can employ the canon (in only two voices, mostly) to such a degree as to create such richness of texture. The same can be found in A Rosary of Variations on Seán Ó Riada’s Irish Folk Mass, but more striking about this piece is its sheer originality. Where else can one find a piece of piano music set so closely to the format of a part of a church service? Respighi’s Tre Preludi sopra melodie gregoriane are only remotely like it. The incantations, the responses of the choir, they are all there, and it is proving very effective, to judge from early feedback from enthusiastic listeners.

A Scottish Triptych is a work of ingenuity, too. ‘Keening Sang for a Makar’ in homage to Francis George Scott takes his initials, translated in to musical notiation (F, G, Es – the German spelling of E flat) and with such economy of means creates a piece that, in some ways, isn’t a million miles away from Busoni’s post-Doktor Faust compositions (think of the Sonatina Seconda). ‘Heroic Song for Hugh MacDairmid’, whom Ronald knew well, conveys the most inspiring sense of space. Marjorie said in one conversation that he was trying to evoke the hills, the mountains, the lochs – Scotland, essentially. He achieves this absolutely, for me. One is instructed in the score to silently depress the white keys of the piano from bottom A to the F below middle C, and play the stately, staccatissimo theme senza pedale. The sympathetic resonance of the undampened bass strings is extraordinary in its evocation of wide-open space, and it makes for one of my favourite moments in all the music I’ve ever played. To finish the set, ‘Chorale-Pibroch for Sorley MacLean’, a proud-seeming work evoking the Great Highland Bagpipe. Again, Ronald’s use of extended techniques is perfectly integrated with the music. After the solemn strumming of strings at the opening, a quieter section a semi-tone below the home key incorporates subtle use of a single pizzicato A flat as part of the melody. This can only be an evocation of the clarsach, the Celtic harp, and achieved through literal replication of the clarsach’s technique (the piano is a harp in a box…) without it being at all gimmicky. Shorter pieces, for children and non-virtuoso pianists, are to be found on this disc, and each and every one of them is as charming and spellbinding as the next.

A Scottish Triptych is a work of ingenuity, too. ‘Keening Sang for a Makar’ in homage to Francis George Scott takes his initials, translated in to musical notiation (F, G, Es – the German spelling of E flat) and with such economy of means creates a piece that, in some ways, isn’t a million miles away from Busoni’s post-Doktor Faust compositions (think of the Sonatina Seconda). ‘Heroic Song for Hugh MacDairmid’, whom Ronald knew well, conveys the most inspiring sense of space. Marjorie said in one conversation that he was trying to evoke the hills, the mountains, the lochs – Scotland, essentially. He achieves this absolutely, for me. One is instructed in the score to silently depress the white keys of the piano from bottom A to the F below middle C, and play the stately, staccatissimo theme senza pedale. The sympathetic resonance of the undampened bass strings is extraordinary in its evocation of wide-open space, and it makes for one of my favourite moments in all the music I’ve ever played. To finish the set, ‘Chorale-Pibroch for Sorley MacLean’, a proud-seeming work evoking the Great Highland Bagpipe. Again, Ronald’s use of extended techniques is perfectly integrated with the music. After the solemn strumming of strings at the opening, a quieter section a semi-tone below the home key incorporates subtle use of a single pizzicato A flat as part of the melody. This can only be an evocation of the clarsach, the Celtic harp, and achieved through literal replication of the clarsach’s technique (the piano is a harp in a box…) without it being at all gimmicky. Shorter pieces, for children and non-virtuoso pianists, are to be found on this disc, and each and every one of them is as charming and spellbinding as the next.

Through close work on Ronald Stevenson’s piano music, I feel as close to the spirit of the man as I will ever be. It will forever be one of my great regrets as a musician that I did not discover his music sooner, but equally it is one point of swelling pride that I was lucky enough to meet him, if only once. The impression he has left on me is very great. Long may his artistic legacy be known.