It is something of a myth that composers tend to die after completing their ninth symphony, based on the relatively few that did so and bolstered by others who are popularly thought to have done so but in fact completed more, such as Bruckner, or fewer, such as Schubert. Substance is further given to the aura surrounding the ninth symphony by the fact that the composers who managed to get there often seem to have reserved some of their weightiest utterances for the work bearing that number: Beethoven, Schubert (if one refers to the old numbering), Bruckner (if one discounts the two unnumbered ones) and Mahler all appear to bear out that hypothesis.

In more recent times, one could also add the names of Allan Pettersson and Robert Simpson, not to mention my good friend David Hackbridge Johnson, whose own Ninth strikes me as being the most monumental of his canon, to the list of composers whose Ninth Symphony seems to have stimulated them to special efforts. All three of the last-named composers went on (have gone on, in the case of DHJ) to compose more symphonies, as did many others who escaped the curse of the Ninth and kept on writing, appearing to be not at all exercised by the spectre of those who had rung down the curtain soon after reaching the fateful number, or, in the case of Bruckner, while attempting to complete it. Shostakovich famously appeared to care not a jot for the mighty shadow of those earlier works, giving us a much lighter offering than any of his previous works in the genre and going on to complete fifteen symphonies. Clearly, between those who didn’t make it to nine and those who exceeded it (a friend recently reminded me that Leif Segerstam’s total currently stands at 344, just in case I started getting big-headed at reaching nine), those who stopped at exactly nine are in a minority.

There seems, then, little objective justification for quaking in one’s boots before embarking on a ninth symphony, but the fact remains that those awesome earlier ninths do give one pause for thought. The choice one is faced with as a composer seems to be to attempt something equally heaven-storming, to give a deliberately trivial two-fingered salute to tradition, or to completely ignore the issue and simply write what one has to write. In point of fact, the decision was taken out of my hands, as I shall now explain.

In 2016, Martin Anderson wrote to me with the following suggestion:

I may be overlooking something you have already done […], but have you ever thought of writing a funeral march (as a symphonic movement or an independent piece), where you really pile it on? Dark, desperate, furious, violent (especially) – a crucible for all the frustrations of the world. You’ll know that Gide said that he couldn’t have written La Porte Etroite without already intending to write L’Immoraliste; well, maybe such a piece could be the opposite of your Festive Overture – a volcanic eruption of anger barely held in place by a relentless tread. I can hear it in my mind – as your piece, a wild, frenetic orchestral showpiece.

In response to Martin’s suggestion, I composed a passacaglia based on the ground from ‘Dido’s Lament’ in Purcell’s opera Dido and Aeneas, which I finished in June 2019, intending it as a stand-alone piece, entitled Rage. But both Martin and, independently, the conductor Paul Mann, having seen the score and listened to the computer mock-up, thought that the piece would make more sense if it followed one or more symphonic movements. Agreeing with them, I set it aside, resolving to make it the final movement of a symphony.

Having recently completed my Sixth Symphony, I didn’t think that this passacaglia would be appropriate for inclusion in the next symphony, as both the passacaglia and the Sixth are weighty pieces and I didn’t feel able to immerse myself once more in the kind of serious symphonic issues that I had just tackled in number six. Not just yet, at any rate. For a symphony to end with Rage, I would have to compose at least two substantial movements to which Rage would be the culmination and I wasn’t ready for that. I therefore decided to write my Seventh Symphony as a more modest piece, intending Rage to be the finale of number eight.

In the event, the one-movement Seventh Symphony grew into a substantial piece in its own right, which was not without compositional difficulties of its own. Much of its material grows from the opening six notes on horns and bassoons, but it turns out that this opening motif is itself derived from the simple runic tune into which the Symphony devolves at the end. The fact that I didn’t learn this until I had been struggling with the piece for some time made it one of the harder symphonies to write.

Having failed to find light relief in the Seventh, I again attempted to do so by turning to an early string quartet written when I was aged 24. I’d dismissed this piece as juvenilia but thought it could perhaps be salvaged by arranging it for string orchestra and filling out the textures. I gave this piece the working title Dark Tidings: Sinfonietta for Strings and sent it to Martin, who thought it worthy of being called a symphony. I disagreed, and Martin suggested I sound out the composer and friend Francis Pott for a second opinion.

At that point, in a totally unrelated twist to the plot, Ken Woods, musical director of the English Symphony Orchestra, messaged me to ask if I had anything for a ‘Beethoven Seven’-sized orchestra. I hadn’t, but offered to send him this piece for strings. He was keen to have it for the upcoming Three Choirs Festival, but wanted it to be called a symphony. By this time Francis had also agreed that the work was worthy of symphonic status, so, bowing to the weight of opinion, I relented and began reorchestrating it to fit Ken’s specification. It’s odd that this early work sounds as modern as any of my more recent symphonies: when I wrote what was to become the Eighth, the First was still fifteen years in the future. Odd, too, that while my first two symphonies still await either performance or recording after a quarter of a century, the Eighth was already on the programme of the Three Choirs Festival before I had even finished reorchestrating it.

Almost without warning, therefore, I was poised to write my Ninth – had in fact already written one movement of it without knowing that it would be part of the Ninth – and so the decision as to the character of the piece had already been made for me. Rage is a large-scale Largo movement, lasting some sixteen minutes, and moving from the most fragile sounds on col legno strings and harp to passages of barely controlled, fist-shaking fury. It clearly required something weighty to precede it, and so I composed three more movements of similar substance to give a work of some 50 minutes’ playing time, all four movements tied together by different uses made of Purcell’s ground.

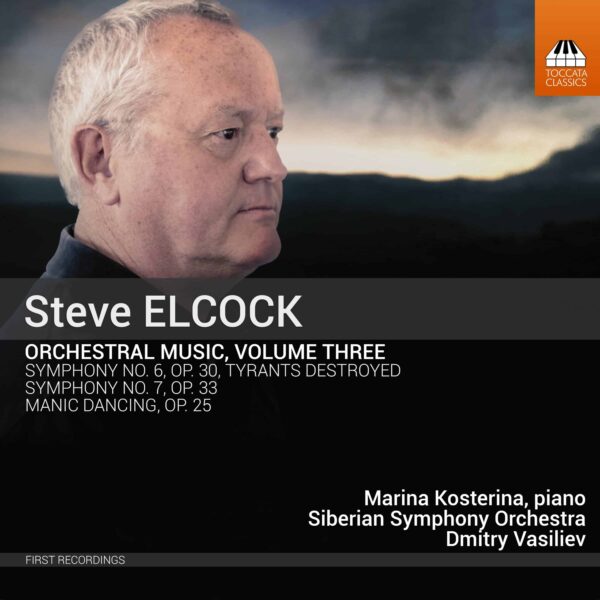

In the summer of 2021, the Siberian Symphony Orchestra under Dmitry Vasiliev recorded the Sixth and Seventh Symphonies, together with Manic Dancing for piano and orchestra. This recording, released on 4 March 2022 on the Toccata Classics label, brings together two of the protagonists in this strange journey that led me unawares to my Ninth, in the shape of these two symphonies. The Eighth, the next stage on the journey, has also been recorded by Ken Woods and the English Symphony orchestra for later release. And Manic Dancing has its own connection to the story.

The conductor Mark Eager, who was to give the first performance of my Fifth Symphony with the Cardiff University Symphony Orchestra on 27 October 2017, suggested that I might like to write a piece for piano and orchestra to be recorded with the pianist Ken Hamilton, along with the Fifth. Always willing to oblige, I came up with Manic Dancing, a concerto for piano in all but name. Unfortunately, the recording didn’t happen, though the orchestra under Mark’s direction gave a searingly committed account of No. 5 in concert.

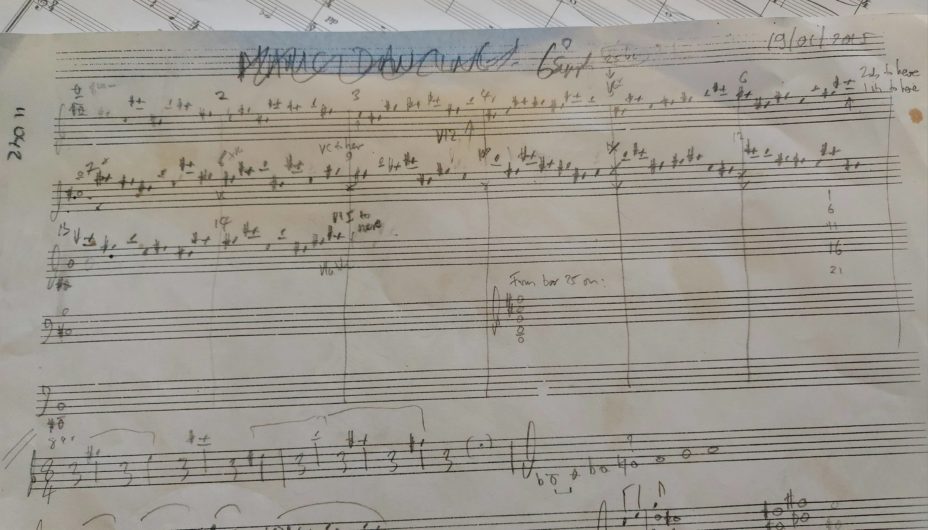

From the manuscript, it appears that I had begun a piece with the title Manic Dancing earlier in 2015, but whatever it was going to be, it wasn’t the piece for piano and orchestra that Mark had suggested I write. I made a totally fresh start on it, but was unwilling to waste this opening idea, and so crossed out the words ’Manic Dancing‘ and replaced them with ’6° Symph‘, thinking to use it as the start of that work. In the event, I didn’t use it for the Sixth either (nothing could be more different from the gloomy opening of No. 6), nor yet the Seventh, and obviously not the Eighth, since it had already been written. It finally came home to roost as the opening of the Ninth symphony.

If there is anything to be learned from this story, I suppose it is that nothing need go to waste and that material found inappropriate in one context can often be repurposed for another, provided one is patient enough. It is perhaps also interesting to note that composition is not the tidy, chronologically ordered process that people may think – at least, not for me. I wrote the last movement of my First Symphony first, while the second movement of my Second was the last to be written. The first part of the Fifth Symphony to be composed was the second movement, while, as we have seen, I began the Ninth with its finale.

I feel I got to No. 9 in something of a rush. It was almost as though someone was saying ’quick: go for it now, while nobody’s looking!’, perhaps Fate’s way of making me confront this hurdle before it was too late. Will I defeat the curse of the Ninth? Am I living on borrowed time? I’m not superstitious, but I’ve made a start on No. 10, just in case. I mean … you never know, do you?

A fascinating insight into the thoughts, processes and disruptions of a composer’s creative life, especially for those like me who appreciate and enjoy music without having the remotest understanding of how it is created for us! Mirroring life, the paths ahead remain a mystery of the unknown, whereas the paths behind us all make some sort of retrospective sense of what was invisible at the time..

As for the worry of life, I would focus on George’ Burns reflection – “If you live to be one hundred, you’ve got it made. Very few people die past that age.” Between now and then, there is plenty of time for another 335 symphonies……

An intriguing account by a fine writer and composer who deserves much more attention than he’s had.

A brilliant composer named Steve,

Whose music had slipped through a sieve,

Was lucky a Scot

Asked “What have you wrought?”

And now: hear what they achieve!