I often play a kind of party game with friends: each participant will offer a recording of a piece of music by a less-well-known composer, or one lifted from total obscurity, taking care not to show the record sleeve or CD case to the others; then by a series of questions the identity of the composer is to be arrived at by the other competitors. The questions might consist of anything that might seek to locate the composer – say, by historical period, nationality, or use of certain compositional traits. One way to attempt an answer is the ‘sounds like’ question. This is a good way to come closer to an answer: perhaps the mystery composer was a student of Shostakovich, thus explaining the bitter contrapuntal development and hollow lurches to the major key; perhaps a post-Brahmsian mahogany texture is knotted with chromaticisms. Then you go through the list of lesser-known Soviets and Regerites. There may even be heated exchanges as to whether a piece does or does not reveal hints of middle-period Alexandrov (Anatoly, not Alexander).

I often play a kind of party game with friends: each participant will offer a recording of a piece of music by a less-well-known composer, or one lifted from total obscurity, taking care not to show the record sleeve or CD case to the others; then by a series of questions the identity of the composer is to be arrived at by the other competitors. The questions might consist of anything that might seek to locate the composer – say, by historical period, nationality, or use of certain compositional traits. One way to attempt an answer is the ‘sounds like’ question. This is a good way to come closer to an answer: perhaps the mystery composer was a student of Shostakovich, thus explaining the bitter contrapuntal development and hollow lurches to the major key; perhaps a post-Brahmsian mahogany texture is knotted with chromaticisms. Then you go through the list of lesser-known Soviets and Regerites. There may even be heated exchanges as to whether a piece does or does not reveal hints of middle-period Alexandrov (Anatoly, not Alexander).

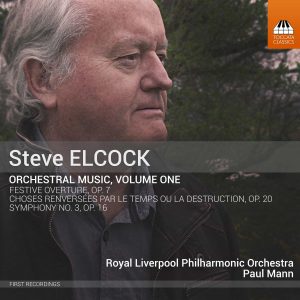

There are now two albums of my orchestral music recorded on Toccata Classics1. The first release lists in the blurb a few composers that my music ‘sounds like’ – although not put in those terms. ‘Influence’ is the standard word used in such attempts, justifiable in the light of a first appearance before a larger potential public of a hitherto ‘unknown’, to give the listener at least an idea what to expect before shelling out cash. What my music sounds like (other than itself – but let’s lay that aside) will vary according to who is doing the listening, something I cannot and have no wish to control. I like a lot of music, really a lot, so I am more likely to be flattered, if not bemused, by comparisons made with Janáček, Pettersson, Vermeulen or whomever.

There are now two albums of my orchestral music recorded on Toccata Classics1. The first release lists in the blurb a few composers that my music ‘sounds like’ – although not put in those terms. ‘Influence’ is the standard word used in such attempts, justifiable in the light of a first appearance before a larger potential public of a hitherto ‘unknown’, to give the listener at least an idea what to expect before shelling out cash. What my music sounds like (other than itself – but let’s lay that aside) will vary according to who is doing the listening, something I cannot and have no wish to control. I like a lot of music, really a lot, so I am more likely to be flattered, if not bemused, by comparisons made with Janáček, Pettersson, Vermeulen or whomever.

I have, of course, been influenced by other composers. Some I have sought as models; others have seeped in unbidden, only to announce their presence by a sly turn of phrase or harmony that in retrospect suggests unconscious involvement. This can only mean there is a network of association, a dialogue, conscious or otherwise, with the past, a context where a work of art can’t avoid being situated. Reading Bloom, I should be anxious, but I’m not2. Influence is part of sense data recalled, assimilated, used for new purposes; part of sense data that if widened to the totality of individual experience might be ‘an infinity of traces’ – a phrase I first came across in a quotation from Gramsci’s Prison Notebooks used as a superscription to Robert Hampson’s poem Seaport3, a work which charts a course through the history of the city of Liverpool (the course is literal in those passages which describe entry into the docks.)

Hampson’s approach is one of traces; he doesn’t seek a grand over-arching narrative; rather, he quotes from statistics, newspapers and other writers in what Hilda Bronstein calls ‘an intertextual fabric’4. The fragments in the main speak for themselves yet become loaded by the context of commerce, slavery and decay, epitomised by the chilling line (surely the focus of the whole poem) ‘no misery / that cannot be rendered / marketable’5. Hampson has deftly and concisely selected from what must be an inexhaustible set of data; no doubt the choices were partly pre-planned, partly intuitive; matters of balance, and the weight of words and line to create the dense emotive force the poem succeeds in thrusting forward. In this way Seaport is a text of texts but one where the selection implies a view taken at a given point in time and place, one that allows the poem to embed itself in those very choices. This sounds Bloomian: texts as commentaries on other texts.

The Gramsci quotation used by Hampson is worth reading in full: ‘The starting-point of critical elaboration is the consciousness of what one really is, and is “knowing thyself’’ as a product of the historical process to date, which has deposited in you an infinity of traces’. Gramsci’s ‘knowing thyself’’ posits a self-knowledge as a ‘product of the historical process to date’ – and yet that ‘to date’ implies surely an artificial stopping-point, since the ‘process’ is ongoing and open-ended; its subject constantly in a fabric of present thought which is woven from immediate physical and mental states buffeted by recollection and projection; more a state of Bergsonian flux. Gramsci’s fixed point, ‘to date’, suggests to me a temporary viewing platform from which in a moment of pretended or momentarily achieved stasis the subject might survey a personal, physical and emotional landscape; the outcrops of event, the still fields of regulated thoughts and memories, sharp ridges of trauma or waterfalls of joy, shadows of lost information or things best buried. This recalls what Geoffrey Thurley calls, after John Stuart Mill, the ‘orchestral landscape’ of Tennyson6. The view is a selection – like Hampson’s selection for his Liverpool traces – one that comes to the forefront while on the viewing platform. Selections can change; memory may falsify over time, half-forgotten things may suddenly loom large or change, as with poets who edit out early verses when making collections and retrospectives of their work; perhaps there will be poems they no longer recognise by poets who was once them but is no longer.7

The Gramsci quotation used by Hampson is worth reading in full: ‘The starting-point of critical elaboration is the consciousness of what one really is, and is “knowing thyself’’ as a product of the historical process to date, which has deposited in you an infinity of traces’. Gramsci’s ‘knowing thyself’’ posits a self-knowledge as a ‘product of the historical process to date’ – and yet that ‘to date’ implies surely an artificial stopping-point, since the ‘process’ is ongoing and open-ended; its subject constantly in a fabric of present thought which is woven from immediate physical and mental states buffeted by recollection and projection; more a state of Bergsonian flux. Gramsci’s fixed point, ‘to date’, suggests to me a temporary viewing platform from which in a moment of pretended or momentarily achieved stasis the subject might survey a personal, physical and emotional landscape; the outcrops of event, the still fields of regulated thoughts and memories, sharp ridges of trauma or waterfalls of joy, shadows of lost information or things best buried. This recalls what Geoffrey Thurley calls, after John Stuart Mill, the ‘orchestral landscape’ of Tennyson6. The view is a selection – like Hampson’s selection for his Liverpool traces – one that comes to the forefront while on the viewing platform. Selections can change; memory may falsify over time, half-forgotten things may suddenly loom large or change, as with poets who edit out early verses when making collections and retrospectives of their work; perhaps there will be poems they no longer recognise by poets who was once them but is no longer.7

How to make sense of the infinity of traces, the plethora of thoughts that inundate? We hear thousands of things, we feel endless sensations, we absorb our surroundings, we read books, throw some aside, hug others close to us. If there is anxiety, it is not of influence but of being overwhelmed by a sheer bombardment. Just confining the argument to music and poetry – there might be dozens of new recordings of new composers and performers to listen to, a hundred poetry books might come out in a few months. What to do? Andrew Duncan’s work on poetry frequently hints at the impossibility of covering this ground: ‘The growth of poetic activity during the 1960s, or perhaps more precisely 1965–75, was of such a scale that an oversight ceased to be possible’8. The literary historian trying to make sense of the plethora might have to resort to contrived selections. As a last resort, one might posit a survey illuminated by individual books, authors and fugitive groupings, only a few of which might hazard a manifesto; groups seeming a good idea at the time, only for their members to disavow membership or at least loosen ties retrospectively9. Groups might only serve as easy pawns to be co-opted into Poetry Wars by the power-brokers of aesthetic conflict; in music, too, we well remember the Brahms v. Wagner war in the nineteenth century or the Glock/anti-Glock arguments re the BBC of more recent decades.10 What Duncan achieves, despite the odds against him, is to reclaim an astonishing number of poets left high and dry by the ‘official’ narrative of poetical history in the last 60 years or so. Scavenging in second-hand bookshops and online, he has amassed books by whole tribes of Lost-Apocalyptics, Neo-Platonists, Experimentalists and Post-Metaphysicals who seemingly wrote into a vacuum ready-made for them by the clerks of mainstream acceptability. Duncan’s books provide fruitful reading lists for the curious; I myself have found and read Peter Yates, Audrey Beecham and Jack Beeching for the first time as a result of reading Duncan and have been enriched by so doing. At Toccata Classics, Martin Anderson has produced getting on for 400 recordings of music working with his declared remit that every release should have at least one work that has never been commercially recorded before; most are entirely of first recordings. Among the more recent releases, forgotten figures like Charles O’Brien, Solomon Rosowsky and Josef Schelb have seen the light of day; the hoary cliché of dusty manuscripts found in attics would seem to be endorsed by actuality. Both Duncan and Anderson are engaged in a form of reclamation. Wherever an historical selection becomes a dogma, people like Duncan and Anderson are vital, since by the nature of the dogma, they will hardly attract support from cliques they hope to subvert. Judging by the output of both these dredgers of history, the work is tireless.11

A Viewing Platform

But back to my idea of a viewing platform. The view I see today makes an odd list. There are events – physical, emotional, triumphs, despairs, love-affairs,12 memories of people and places, things lost but leaving a residue, specific artists that made a deep impression by their work and personality. Here is the list, a snapshot of landmarks, but already shifting as I write:

- treading in mud somewhere in the woods near Sutton Coldfield

- losing a glove at the age of four – actually pushed down a drain by Fiona Neave

- seeing the road through a rusty hole in the footwell of a Standard 8

- my first violin – its sound and the grain of its wood

- watching goods trains over the wall in Preston

- the almost white blond hair of a girl seen from the back in a school assembly

- the introduction of the word ‘depression’ into the family lexicon

- constructing Verdun-like defences in the rubble created when an extension was built; deaths of a thousand plastic soldiers

- Total Confusion at music college

- Marcus Wright playing Parker and Coltrane on the gramophone

- Orgreave on TV

- finding the score of Brian’s Second Symphony in Victoria Library, singing it on the Tube back to Ladbrooke Grove, singing it to my surprised wife

- my first teachers, especially Martin Wilson, Louis Rutland, Fabien Smith and Leonard Silver

- playing Haydn string quartets for ever

- Art Blakey at Ronnie Scott’s – the doorman looked at me, a runty kid trying to get into the club, and put me in a seat directly in front of Blakey’s kit. He winked.

- Harold Dexter – ‘Bloody sopranos!’

- meeting Tippett (‘such a love’) and Lutosławski

- friendships with composers: Ronald Stevenson, Michael Garrett and Justin Connolly.

- a walk through a field in Quercy-Calmes, endlessly repeated in dreams.

- hospital corridors, endlessly travelled in dreams.

Well, I am stepping off the platform now since I can see too many things rushing about like agitated sheep. The volatility of recall might counter the idea that the above is merely a ‘situation-report’13 for the list gives a flavour of the mind’s working, what is in the air, what may or may not feed into creative work, rather than a static reading-off of data. When the work comes, the intuition is paramount but I don’t think of intuition as a disembodiment, rather it is fed by things that lie deep but might throw up shafts of light, just like landmarks that orientate a view.

Bruckner

I should flesh out some of the musical influences – not composers who I consciously chose as models but those who made a number of differing but strong impressions. Like Duncan with his reclaimed land of lost poets, I was always attracted away from the mainstream – the accepted canons of great composers as outlined in the histories of music I read as a teenager; this despite my abiding love of ‘the classics’. My first outsider was Anton Bruckner – yes, in the 1970s there were still many opinions received from books that predated Robert Simpson’s more laudatory study14 of that composer which were almost kneejerk reactions for those wishing to do him down: ‘too long’, ‘too boring’, ‘too Catholic’, ‘he was a weirdo’, ‘he was a simpleton in peasant clothes’, ‘he wrote the same symphony nine times’ (actually eleven if you count the ‘Studiensymphonie’ and ‘Die Nullte’) – all these comments, versions of which I heard at the time, formed a bulwark against Bruckner’s acceptance into the canon. Bruckner’s music is nowadays an established part of the repertoire but in 1975 I felt almost like a rebel for turning up to music lessons with scores of his symphonies tucked under my arm, daring friends and teachers to scoff. They did. That made me more determined. Was there a reason beyond the effect the music had on my senses; the magnificent vistas of the heart opened up by his metaphysical meditations in sound? A desire for exclusive knowledge? A desire for a secret text that only I had the key to? An aid to my then devout faith? A desire for a fellow in suffering? – for I knew at once how Bruckner suffered upon reading all the biographies I could get my hands on. All these solipsistic reasons might be traced to some half-hidden thought or feeling; their exact triggering a matter for futile attempts at pinpointing. But I knew Bruckner would be my special companion.

English Late-Romantic

English Late-Romantic music was much neglected by the organs of culture in my youth. I devoured it – my local library (then perhaps, libraries were the only organ of culture where such things could be found) had many LPs of Ireland, Bax, Moeran, Butterworth, Holst, Bridge and others.15 My feelings about this music fell in with poets I read at the time: Hardy, Edward Thomas, Yeats. Again official bores trumpeted their disdain for these Celtic-Twilighters or Fuddy-Duddies, critically deaf to the immense subtlety of composers moving from a Handelian and Brahmsian inheritance into something unique and suggestive – as if composers had at last caught up with Turner, Blake and Samuel Palmer and struck out from the path of Continental influence. There were many British critics that wished to beat their own and renew with eager resolve Oscar Schmitz’s branding of England as ‘Das Land ohne Musik’.16 A new degree of ignorance was achieved when, after I suggested Rubbra as a composer worth including in a concert I was involved in, a fellow organiser dismissed this subtle master as ‘French slush’, whatever that is.

Skryabin

Later I discovered the intoxicating world of Skryabin – yes, still described as ‘egregious’ by a well-known reviewer within the last few years. Who said that hearing Skryabin’s The Poem of Ecstasy made them want to leap around like a wild horse? That seems a valid response. I lived for a while as a synaesthesiac, seeing colour and sound and smell as somehow expressions of the same thing – is that not indeed the case if they are taken as wave forms? But the delirious Russian was not for Wilfrid Mellers; I think I am right in saying that Skryabin is the only composer for whom he comes off his stool of historical impartiality, assuming an almost moral posture in order to denounce Skryabin’s ‘limpid flaccidity’, his ‘masochism and auto-eroticism’, and to character-assassinate him further as ‘by turns silly, pathetic, horrifying, a portent of Europe’s sickness’.17 These few pages of my old copy of Harman’s and Mellers’ Man and His Music bore marks of well-thumbed rage.

Havergal Brian

I was already delving into what others regarded as eccentric or even crackpot areas of the repertoire. Yet I went for the obscure within the obscure: Havergal Brian. I’ve written elsewhere about him so I’ll be brief here.18 His music really made a deep impression on me as a teenager. I was by that time studying the avant-garde; many nights listening to Boulez, Nono, Messiaen, Ligeti, and getting scores to pore over when I could. Brian was something different again – it wasn’t only the sound of his music; brooding, smoky, sometimes heavy-treaded, at other times mercurial and baffling – all this within a loose tonal framework; but also the sense of an historical disjunct. He was a man so late rediscovered,19 such a mixture of new and old, tender and brutal, the nostalgic and the ironic, that he seemed ‘steam-punk’ before that term had been invented. His vision, and I think I will use that word, is very different to other composers of his time; it seems informed by his poor, industrial background in The Potteries, bolstered by communal activity as provided by churches, music clubs and festival choirs – the historical process in which Brian had been ‘deposited’, to use Gramsci’s term, and one that was perhaps unusual for a composer. Brian’s idylls are besmirched with clay dust. His gothic is not just of cathedrals but also of kiln cones spreading like thickets across towns; from my viewing platform I can see quite a few kilns, since a holiday to The Potteries has left indelible traces.20 There is something Blakean about the music, a music that calls up massed choirs to sing the Te Deum; only the sooty backdrop is of ‘satanic mills’ – this clash of faith and dire working conditions gives Brian’s aesthetic an edge over easy characterisations of religious certainty.

Brain’s was a musical landscape reclaimed from obscurity by Robert Simpson and those musicians he was to persuade to take on the job of performance. I’ve done a little of this reclamation myself by recording some Brian songs and performing some very unfashionable composers: Elaine Hugh Jones, Denis ApIvor, Erik Chisholm and Graham Peel, to mention only four of them. The process of retrieval goes on, the memory sump is always awash, new vistas open up continually – yes, this can cause anxiety, a kind of sensory delirium, only stopped by long walks and good company. But mainly I feel what James Keery calls an ‘elation of influence’.21 Instead of a wholesale rejection of the past, or a dogmatic selection from it, there can be an embracing of what its infinity of traces can offer; that might even mean a kind of ‘apprenticeship to a revered master’.22 For my own ongoing work I prefer emulation to annihilation.

I still listen and read as much as I did when I was in the first bloom of enthusiasm for music and literature – new wonders abound: terrific new pieces by Fridrich Bruk and Steve Elcock,23 recent extraordinarily dynamic poems by Keston Sutherland24, seeing Cecil Collins’ paintings for the first time in the Tate Gallery – another link back to Blake. Like Robert Hampson, there are choices to be made from the flux, snapshots where the mind can take stock; a reading of data that once coded in the artwork immediately sets off into Tennyson’s orchestral landscape.

I still listen and read as much as I did when I was in the first bloom of enthusiasm for music and literature – new wonders abound: terrific new pieces by Fridrich Bruk and Steve Elcock,23 recent extraordinarily dynamic poems by Keston Sutherland24, seeing Cecil Collins’ paintings for the first time in the Tate Gallery – another link back to Blake. Like Robert Hampson, there are choices to be made from the flux, snapshots where the mind can take stock; a reading of data that once coded in the artwork immediately sets off into Tennyson’s orchestral landscape.

©David Hackbridge Johson, 2018

- Volume One (TOCC0393) is available now; Volume Two (TOCC0452), with Symphonies No. 10 and 13 and Motet No. 6, will be released in July.

- Harold Bloom, The Anxiety of Influence, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1973.

- Robert Hampson, Seaport, Shearsman Books, Exeter, 1995.

- Ibid., p. 81.

- Ibid., p. 43 (italics in original).

- Geoffrey Thurley, The Ironic Harvest, Edward Arnold, London, 1974, p. 3.

- Andrew Duncan provides a good case of this when comparing the two ‘collecteds’ made by Kathleen Raine, the first made in 1956, the second covering the years 1935–80 but missing out much of the fine poems of the 1940s. Cf. Andrew Duncan, The Council of Heresy, Shearsman Books, Exeter, 2009, p. 75.

- Ibid., p. 295. Duncan provides some scary numbers to back up this impossibility in his essay Affluence, Welfare, and Fine Words: General Introduction, and these covering only the years 1960–97: ‘28,000 titles of new poetry […;] a count of 6000 poets’. Cf. Website

- Or doubt that these groups really existed in the way they are portrayed; Peter Riley, often stated as being a member of ‘The Cambridge School’ has downplayed the existence of any formal poetic associations while he was at Cambridge. He goes on: ‘I’ve discovered very gradually that associations of any kind among poets are marginal to the central creative act’. Cf. an interview he gave to Varsity magazine in October 2012.

- I have often seen the phrase the ‘William Glock regime’ in articles lamenting his promotion of the avant-garde at the BBC in the 1960s. This Music War sputters on, kept alive by lone snipers who, with admitted skill, can fire with their heads in the sand.

- My own experience with Martin is perhaps typical of this tireless energy; despite having known him for 30 years I hadn’t got around to telling him about my composing activities (very few people knew, to be honest). Within a few months of my rather speculatively showing Martin my Ninth Symphony, a conductor, Paul Mann, and an orchestra, the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra, were engaged for a recording.

- In spite of the ironic distances so insisted upon by certain post-war critics, it might now be confessed that these triumphs and disasters might thread through creative work and occasionally appear as a bright, even livid, patterning – for which, cf. Robert Lowell: ‘Why not say what happened?’

- Thurley’s term; he cautions against it: op. cit., p. 36.

- Robert Simpson, The Essence of Bruckner, Gollancz, London, 1967.

- It doesn’t anymore; the music section in Sutton Library is virtually non-existent. Much of their stock is now in my own collection; all records and scores having been sold off over the years. I have an ambivalence, in that the collection is huge (there are thousands of records and scores here now) and yet what was once available to all is now just mine. I became a composer because of what I heard in my head, but I could only refine this by study in Sutton Library; this recourse has now been ruthlessly cultured out by a form of Cretinous Corporate Philistinism. The precious knowledge-base of passionate librarians has been lost; they were culled, and like a coal mine that gets closed, the seams can never be opened, since flooding quickly drowns the galleries. This sorry story seems to appear as a footnote in almost everything I write.

- Oscar A. H. Schmitz, Das Land ohne Musik: Englische Gesellschaftsprobleme, Georg Müller, Munich, 1914. Does the date of publication indicate that this book was propaganda in light of deteriorating foreign relations?

- Alec Harman and Wilfrid Mellers, Man and His Music, Barrie and Rockliff, London, 1962, pp. 921–22 (from the section of the book written by Mellers). Indexologists may like to note that the ‘horrifying’ composer is listed under ‘Scriabin’ and ‘Skryabin’. Since the old copy I had as a student has long since disintegrated, I struggled to find the evidence of Mellers’ odd fit of hatred against Skryabin as aperson, since a) there were no violent thumb-marks on my new copy, and b) the index name ‘Scriabin’ only led to passing references in a passage about Messiaen. But the offending passage can be found by checking ‘Skryabin’ in the index. Having seen some of the wonderful brightly coloured shirts sported by Mellers, I attempted a mystic chord-infested prelude based on the system devised by Skryabin for his colour organ, his tastiera per luce, and dedicated (but not alas sent) to the historian. This work took flaccidity to new levels. Mellers notes that Wagner was a nasty fellow as well but he is let off the hook by means of appeals to ‘truth’, or something.

- In several articles on the Havergal Brian Society website.

- Mainly by Robert Simpson.

- Of Brian’s birthplace there is no trace since the roads were later redeveloped, yet in the Hanley Pottery Museum I bought an archive map of the area which showed the town at around the time of Brian’s birth. Traces on maps: a whole other topic.

- James Keery, ‘Schönheit Apocalyptica’, Jacket 24 ‘The “anxiety of influence’’ needs to be balanced by a sense of the elation of influence’ [WHOSE ITALICS?].

- Ibid.

- Both stablemates on Toccata idics: Fridrich Bruch & Steve Elcock.

- The best way to explore his poems: Keston Sutherland, Poetical Works 1999–2015, Enitharmon, London, 2015.