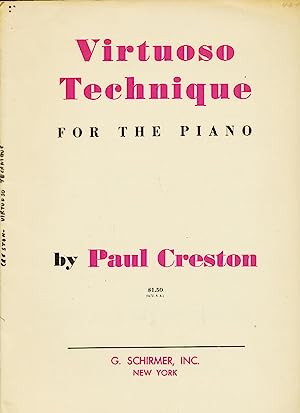

My introduction to Paul Creston was through his Virtuoso Technique – a book of finger exercises so demanding and so unusual that I couldn’t help wanting to know more about the composer who had written it. I was in my late teens and was living in New York, a twenty-minute walk from the Lincoln Center branch of the public library, and I spent an afternoon browsing the stacks for music by Creston. I could tell from the page that the writing was dense and acrobatic; I also noticed that the harmonies looked warm and voluptuous. I checked out some scores, played through them at home, confirmed that they were every bit as difficult and as attractive as they looked, and made a mental note that Paul Creston might be someone to look into someday.

At the time, I was becoming acquainted with the works of Vittorio Giannini, a once prominent and beloved composer whose music had fallen into such obscurity that it was necessary to request ‘authorized photocopies’ of his piano music from his publisher; the actual scores were no longer available even for reprinting. I was also learning the complete piano works (all two of them) of Peter Mennin, the former president of Juilliard whose Third Symphony had been premiered by the New York Philharmonic while the composer was still finishing his PhD, but whose piano sonata had never been recorded. It baffled me how such respected composers, so entrenched in the upper reaches of the music world, had vanished from the concert stage. I included two pieces by Giannini on my first recording, along with works by Franck and Bloch;1 but the teacher with whom I was studying had qualms about my devoting an entire album to unknown composers and becoming labeled a ‘niche’ pianist, and so I put the Mennin aside after a few local performances.

I took a hiatus from my performance career in my mid-twenties to focus on my education. I received degrees in philosophy and religious studies, learned Sanskrit and wrote articles about William James and about rhetoric in Shakespeare. After an abortive attempt at a Ph.D., I was, at 34, too old for young artists’ competitions and in a prime position to focus on the unusual repertoire that had been my strongest interest during my early training.

After several months of playing nothing but finger exercises (including Creston’s) to get my technique back after ten years away from the piano, I had lunch one day with the musicologist Walter Simmons. Walter and I had become friends during the early part of my career, when, unbeknown to each other, we were both petitioning the bank at which Giannini’s unpublished manuscripts were in storage to release copies of his music. The administrator of Giannini’s estate put us in touch, and Walter began sharing his encyclopedic knowledge of American traditionalist composers with me. At lunch, I told Walter I was ready to begin recording again and proposed that I finally record the Mennin pieces I had left behind years before, along with the piano music of Norman Lloyd, who had been an important teacher at Juilliard and Oberlin but had never had a huge profile as a composer, despite having written numerous orchestral works, a large-scale piano sonata and several collections of charming miniatures. I recorded that programme in 2012;2 reviews voiced astonishment that the Mennin Sonata had languished unrecorded for a full half-century despite being widely considered one of the greatest American piano sonatas in the repertoire.

This material has become the sole focus of my performance career: to bring attention to great music that has been neglected. After the Mennin/Lloyd CD, I recorded all the non-sonata piano music Vincent Persichetti wrote in the first half of his career, including six sonatinas, three volumes of Poems and two serenades.3 These pieces were not world premieres, but they had never been collected in one album. Next, I recorded some unpublished music by Vittorio Giannini that I found among one of his students’ papers, but the release of that album has been delayed while awaiting copyright permission from Giannini’s estate.

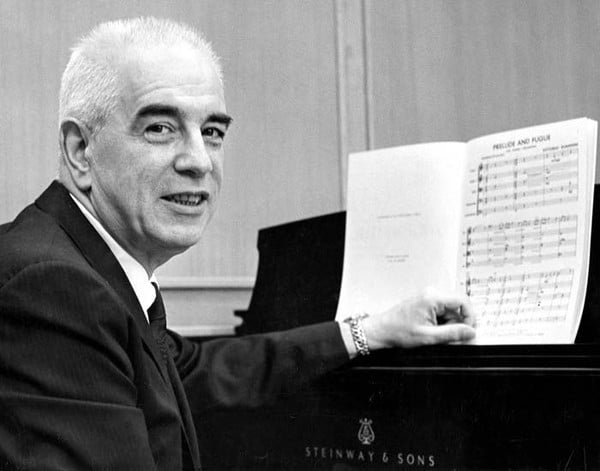

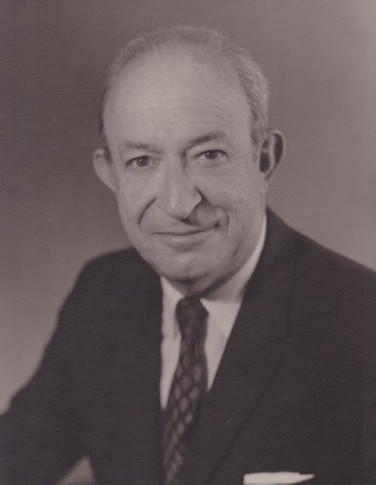

Throughout these various recording projects, Creston’s name remained on my mental landscape. Occasionally, I’d accompany students in a saxophone studio and come across Creston’s saxophone sonata. I once accompanied a marimba student on Creston’s Concertino for Marimba. But Creston’s career was as baffling to me as that of the other composers I had devoted myself to. Here was a composer who had beaten Copland, Gould, Harris and Schuman in a competition for the New York Music Critics’ Circle Prize; one of three composers the Boston Symphony chose as most representative of American music when it performed in the Soviet Union in 1956; and now known primarily by advanced students of unusual instruments suffering from a dearth of solo repertoire.

Walter had mentioned that there was a large-scale work by Creston, the Three Narratives, that had never been recorded. There were also ten volumes of pieces called Rhythmicon, which systematically made use of various ideas Creston had developed about rhythm. As soon as I finished recording the Giannini pieces, I began browsing through Creston to see how the pieces struck me.

It was immediately obvious to me that the Three Narratives are masterpieces: top-level writing both in terms of pianism and in terms of self-expression. The Rhythmicon progressed much like Bartók’s Mikrokosmos: though the first few volumes are beginner-friendly, the bulk of the 123 pieces in the collection are full-fledged concert works – full of wit, charm, and dazzling rhythmic effects.

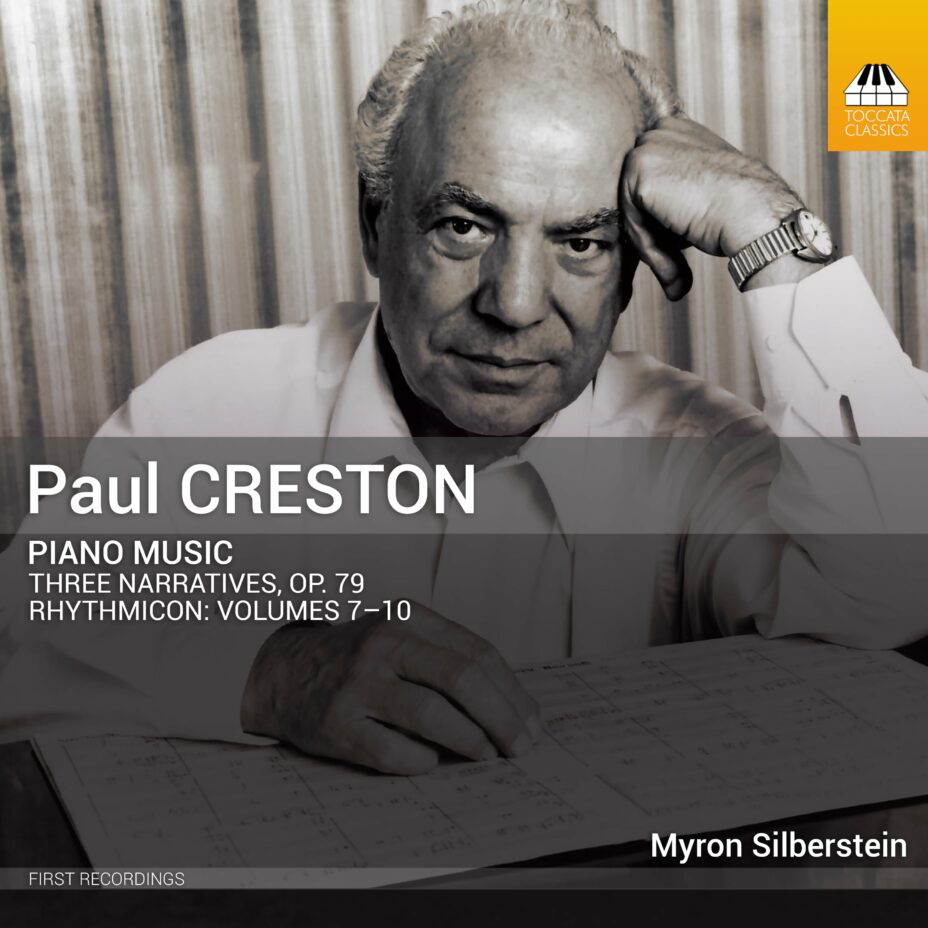

I firmly believe that every piece on this album4 deserves a place within the canon of standard piano repertoire. It is my enormous privilege to introduce it to listeners via my Toccata Classics recording.

- Connoisseur Society CD 4208 (1996).

- Naxos 8.559767 (2014).

- Centaur 3632 (2018).

- Toccata Classics TOCC 0674 (2023).