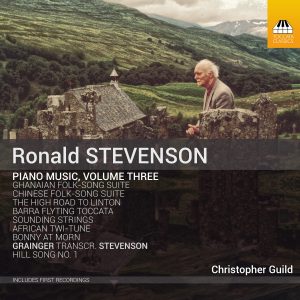

The third volume of Ronald Stevenson’s piano music (TOCC 0403, released on 1 February) has been probably the most interesting album of his music I’ve worked on so far, because I’ve rarely had the chance to study European classical music, with its roots in the late Romantic style, that so successfully melds with indigenous music from around the world. Not only is it fascinating music; it is highly original, surprising and delightful.

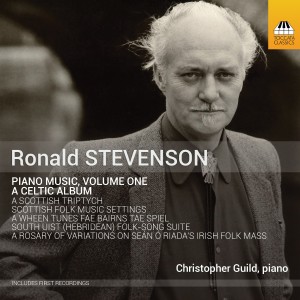

The first album in this series – which I foresee continuing for some time – was an exploration of Stevenson’s piano music that has its inspiration in Scotland, with a brief foray to the music of Ireland (TOCC 0272). What made an exploration of Scottish-rooted music so valuable an experience for me was the opportunity to reconnect with my own roots. Since 2005, when I was 18, I have been domiciled primarily in the south of England and I sorely missed life north of the border, especially when I moved to London. Rediscovering Scotland through music has been a very different experience from what it would have been if I’d stayed at home, and perhaps it was possible only after having been away.

Distance by its nature offers one the chance to scrutinise and evaluate from a different perspective – a much more objective one. My study of Scottish piano music is born not of any overtly nationalistic feeling, but out of sheer admiration for the wealth of seriously fine music composed by my compatriots, music that simply isn’t known. It is comforting that I, as a Scottish-born musician, have a musical history of which I can be a tiny part. I am still figuring out how Scots musicians, throughout their upbringing, can remain so blindly unaware of Scottish composers: I for one had no idea such a thing existed until learning about Sir James Macmillan, some six or seven years after beginning to pursue music seriously. (Thank goodness for fellow expat Scot, Martin Anderson, for creating Toccata Classics and thereby a platform for some of this music. We would be much more in the dark without this label.)

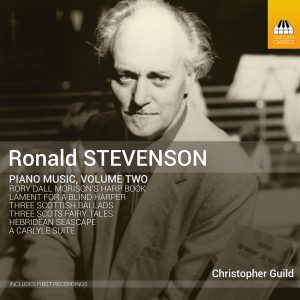

My second volume of Ronald Stevenson’s piano music (TOCC 0388) took this Scottish study further, also broadening awareness of an English composer whom the mainstream no longer considers: Frank Merrick (with reference to Stevenson’s Hebridean Seascape). The intention for this album was, through the choice of programme, to act out Stevenson’s implied wish for Scottish people to realise their national identity as a means of going beyond it: ‘I think all great art aspires beyond nationalism […]. But I am convinced that people’s culture cannot get beyond nationalism until it has realised it. Scotland hasn’t’1. I recently wrote an article for iScot magazine, published in the January 2019 issue, in which I discuss this idea at length.2

Volume 3 completes the exploration of Scottish-themed repertoire by means of Stevenson’s settings of a number of traditional songs and tunes. The High Road to Linton was an obvious piece to include: the Stevensons have lived in West Linton, in the Scottish borders, since the early 1950s, and their beautiful old stone house is thought to have been home to the fiddler who wrote that tune. In Stevenson’s

Then there’s the suite Sounding Strings, which begins to take us beyond Scotland. Fourteen pieces in total, it is meant for harp or clarsach, with performance permissible on piano. Given its popularity among harpists, I’m still puzzled that no-one’s thought to record it yet, and though it’s satisfying now to hear it on disc and online, I’m a little sad for the music that it should played by a keyed harp in a box (for that’s all a piano is) and not an actual harp. No matter. The suite sets Scottish folk tunes as well as some from Wales and Ireland, and then on to the other Celtic nations, namely Cornwall, the Isle of Man, and Brittany.

Sounding Strings serves as a springboard to explore music which Stevenson assimilated from the world beyond that of the Celts. Stevenson begins his wider exploration of indigenous music after returning from a four-year tenure of the chair of Senior Professor of Composition at the University of Cape Town in 1962–65. Before that stint abroad, he began a now renowned correspondence with Percy Grainger (published as Comrades in Art by Toccata Press). Grainger, along with Busoni, remained a profound influence on the young Ronald Stevenson, whose African Twi-Tune was maybe the first gesture towards ‘world music’ (a convenient, but insufficient, label for any non-western music) and which, on one level, takes its form from Grainger, who wrote a number of these pieces. A ‘twi-tune’ – the term is itself a Graingerism – is literally two melodies played simultaneously, and with some appropriate harmonisation, in this instance ‘The Bantu and Afrikaaner National Hymns Combined’, as the subtitle has it. It is fun to experiment with this idea. Stevenson wrote his Twi-Tune in South Africa. In his hands, it expresses a deadly serious message: the wish, in the face of Apartheid, to see all races unite in their common humanity. It is as important a message now as it ever was, is representative of much of Stevenson’s thought in and beyond music, and therefore is placed, symbolically, at the start of the programme.

The Ghanaian Folksong Suite and Chinese Folksong Suite are also Graingeresque in their influence. Both make for uncommonly beautiful and distinctive piano music, as eminently approachable as they are playable (though the ‘Leopard’s Dance’ in the Ghanaian suite is surprisingly fiendish: being in the Dorian mode on D, it doesn’t require the pianist to play any black keys, and you realise how much you rely on black keys to retain a sense of where you are on the keyboard when suddenly they’re taken away from you!).

In view of the underlying influence of Grainger, it would be wrong not to include Stevenson’s most important ‘Grainger work’: the latter’s transcription of the former’s Hill Song No. 1. A fellow pianist of mine recently remarked that, for him, Stevenson’s version for solo piano has even more immediacy than the original. For my part, I enjoy the original version, for wind ensemble. But the piano, by its nature, allows for more transparent textures, and given the sheer density of the writing in this piece, the piano (and Stevenson’s occasional sensitive rearrangement of registers) allows us to hear so much of the wonderful interplay of parts that carries this piece forward. Listen out for Stevenson’s insertion of another Percy Grainger song about halfway through – a stroke of genius.

One thing I must point out is that this transcription was made for Stevenson himself. It’s a huge feat of pianism, and like pretty much all his work there was no commercial incentive. Nor was it a commission. Back in the 1960s, very few people were playing either of Grainger’s Hill Songs, which are both scored for wind ensemble. Stevenson simply wanted to hear this music for himself, as often as he liked; he adored Hill Song No. 1. Grainger made a version for two pianos: but Stevenson had only one piano at home. No barrier there: with a titanic technique and an unrivalled capability for transcription, he managed the whole thing on one instrument. Here it is. There exists Stevenson’s own recording from an Altarus recording from the 1980s. How I’ve approached the piece is quite different, so my recording is offered very much as an alternative; but, moreover, as a tribute to this utterly fantastic music. The end I find spellbinding.

Volume 4, now in preparation, will takes us in a slightly different direction, although still one based around the idiom of song. It will see the first complete recording of Stevenson’s L’Art nouveau du chant appliqué au piano, a suite from Paderewski’s opera Manru and a transcription of Stevenson’s own Nine Haiku, among other works.

I must thank Iain

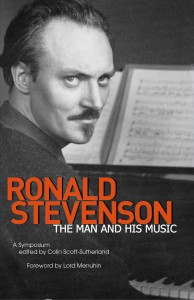

- Letter to Ateş Orga, dated 30 April 1968, quoted by him in ‘The Piano Music’, Ronald Stevenson: The Man and his Music, ed. Colin Scott-Sutherland, Toccata Press, London, 2005, p. 60.

- iScot, January 2019, pp. 96-99