John’s death on 13 February was not unexpected – indeed, he had given his brain tumour a good fight and long outlived his doctors’ prognoses. But he had much music still left to write. And not only music: a few years ago he rang me up and asked if Toccata Press might be interested in publishing a book on Sibelius’ orchestral music, because he wanted to write one; not half, I told him, ready when you are – and now, of course, I realise I should have given him a deadline. Another McCabe literary project, which I initially suggested as a way of marking his 75th birthday (which fell on 21 April 2014), was John McCabe on Music, a collection of his writings, to be edited by Guy Rickards, who has written widely on John and his music. John’s illness booted that idea into the long grass – there were far more pressing matters to think about – but we are in the process of reviving it and hope now that we will be able, funding permitting, to bring it out in a year or two as a memorial volume in the Toccata Press series ‘Musicians on Music’.

John’s death on 13 February was not unexpected – indeed, he had given his brain tumour a good fight and long outlived his doctors’ prognoses. But he had much music still left to write. And not only music: a few years ago he rang me up and asked if Toccata Press might be interested in publishing a book on Sibelius’ orchestral music, because he wanted to write one; not half, I told him, ready when you are – and now, of course, I realise I should have given him a deadline. Another McCabe literary project, which I initially suggested as a way of marking his 75th birthday (which fell on 21 April 2014), was John McCabe on Music, a collection of his writings, to be edited by Guy Rickards, who has written widely on John and his music. John’s illness booted that idea into the long grass – there were far more pressing matters to think about – but we are in the process of reviving it and hope now that we will be able, funding permitting, to bring it out in a year or two as a memorial volume in the Toccata Press series ‘Musicians on Music’.

The two key words, of course, are ‘funding permitting’: Guy gave me a lift to John’s funeral on 3 March and on the drive down, we made a rough calculation of the amount of John’s music still to be recorded. It left me open-mouthed with amazement at John’s sheer industry: there are, for example, no fewer than 22 McCabe concertos. And so, funding permitting, Toccata Classics will be trying to make some inroads into that huge corpus of music in the years ahead.

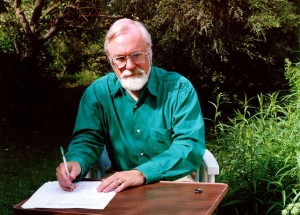

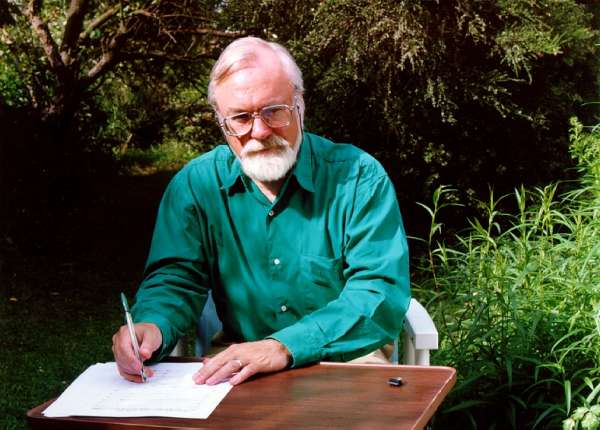

First, though, if you didn’t know John personally, below you can make your acquaintance with this marvellous man in his own words; and if you did, please give us your own memories in a comment on this blog posting.

Being Yourself: John McCabe in Conversation

The name of the English composer and pianist John McCabe may not yet be as familiar in North America as it is in Britain and Australia, but a new Hyperion release (CDA67089) of McCabe’s Of Time and the River (his Fourth Symphony), coupled with his Flute Concerto and released this September to mark his sixtieth birthday earlier this year, should do much to alert American readers to a powerful and vital voice in contemporary music. It was through the efforts of Hyperion that the music of McCabe’s friend and colleague, Robert Simpson, not quite a generation older, made the jump from local enthusiasm to master of world standing. With the Third, Fourth, and Fifth String Quartets already available (CDA67078), Hyperion has now made a valiant start to performing the same service for McCabe – and his potential audience. And listeners who have responded readily to Hyperion’s Simpson discs should embrace McCabe’s music with enthusiasm: there are many points of contact between the two men’s music, though whereas Simpson’s might be characterised as ‘British-Nordic,’ McCabe’s is ‘British-European’. And whereas Simpson set his teeth against serialism, McCabe, though a tonal composer, has been happy to take what he wants from everything he hears around him and to build it into his own soundworld.

The name of the English composer and pianist John McCabe may not yet be as familiar in North America as it is in Britain and Australia, but a new Hyperion release (CDA67089) of McCabe’s Of Time and the River (his Fourth Symphony), coupled with his Flute Concerto and released this September to mark his sixtieth birthday earlier this year, should do much to alert American readers to a powerful and vital voice in contemporary music. It was through the efforts of Hyperion that the music of McCabe’s friend and colleague, Robert Simpson, not quite a generation older, made the jump from local enthusiasm to master of world standing. With the Third, Fourth, and Fifth String Quartets already available (CDA67078), Hyperion has now made a valiant start to performing the same service for McCabe – and his potential audience. And listeners who have responded readily to Hyperion’s Simpson discs should embrace McCabe’s music with enthusiasm: there are many points of contact between the two men’s music, though whereas Simpson’s might be characterised as ‘British-Nordic,’ McCabe’s is ‘British-European’. And whereas Simpson set his teeth against serialism, McCabe, though a tonal composer, has been happy to take what he wants from everything he hears around him and to build it into his own soundworld.

McCabe is currently much better represented in the recording catalogs as a pianist than as composer. His complete recording of the 62 Haydn keyboard sonatas for Decca/London made history in the mid-1970s and has been re-released on twelve CDs. McCabe, born (like The Beatles) in Liverpool in the north-west of England, has always been a stalwart defender of British music, and the lists feature his performances of Bax, Bridge, Ireland, Howells, Joubert and Walton, among many others. Oddly enough, though, after a 1977 RCA LP, two decades went by without anyone asking McCabe to record his own music until now when, shaming the professionals, the British Music Society – of which McCabe is President – brought him into the studio for a disc of piano works, including the important Haydn Variations of 1983.

And the microphones have quite a lot to catch up with. There are some 150 compositions in his worklist: Four orchestral symphonies between 1965 and 1994, as well as one for organ from 1961 and another for ten winds (1964); twenty concertos (including four for piano, and two each for violin and for harpsichord); a good number of other orchestral pieces, chief among them the esteemed Chagall Windows (1974), the Variations on a Theme of Hartmann (1964), the song-cycle Notturni ed Alba (1970), and the tone poem Fire at Durilgai (1988). McCabe has also produced much for the brass band, a tradition that still thrives in the north of England, and it is his brass-band music that so far has fared best on disc, with his Cloudcatcher Fells, the test-piece for the national competition in 1985, out in four different performances. A distinguished chamber musician, he has also written for smaller groups: the five string quartets, several trios and works for a variety of other combinations. His own instrument has benefited to the tune of sixteen large-scale piano works. And as if that wasn’t enough evidence of industry, there are also seven song-cycles, choral music, organ music, music for the stage (two operas, three ballets and a music-theatre piece) – and a Miniconcerto for organ, percussion and audience, playing 485 penny-whistles!

I began my conversation with John McCabe by observing that (to my ears, at least) his music was clearly that of an English composer. He seemed surprised. ‘Is it?’ Well, not in the sense that, say, Simpson’s or Edmund Rubbra’s is; and there’s no English pastoralism. ‘I wouldn’t think of myself as English at all – I’m not English by blood. My father’s family was Scots, and possibly a little more Irish; and my mother’s family was German, with a little bit of Swedish and some Finnish and supposedly some Spanish, but basically German: she was born in Germany. I was born here [in England], and educated here, and I am English, but I have never regarded my music as being English at all, although I am devoted to “English music” – which I persist in calling “British music”. But I’ve never felt English in that respect, as an “English composer”; I’ve never felt my music was. But if I’m played abroad, in Germany, for instance, they say, oh, this sounds English. It’s rather like Alan Rawsthorne or Peter Racine Fricker after the War, for instance. If Fricker’s music was played abroad, they said, this is English music. Whereas if it’s played here, they say it’s clearly a Continental style.’

Yet McCabe’s Fifth Quartet has a kind of ecstatic quality that reminds one directly of Michael Tippett. ‘Yes, I think that that derives from the quality I find inspiring in other composers rather than something I find inspiring in it as a representation of English music. I don’t even regard Tippett as an English composer. At the same time I do feel part of a tradition, and I feel very strongly that Tippett is clearly part of that tradition. Nevertheless, it’s the ecstatic quality that I find inspiring, and not the fact that it’s English. Does that make sense?’

Another component characteristic of British music, to my ears, is what one might call a visionary element – John Tavener is perhaps most obvious contemporary example, but even in a hardcore humanist like Robert Simpson, there is also a visionary quality. ‘Oh, very visionary. It will probably surprise you to think of this, but the visionary is the type of composer I go for most. I go for the humanitarian and the visionary – Nielsen and Sibelius, if you like, who switch roles every now and then, of course, and Vaughan Williams, who is one of my great heroes and always has been since childhood. I find, for instance, the Ninth Symphony a deeply moving piece because of that extraordinary visionary quality, particularly near the end. Here is a man at the age of 85 just about to discover a completely new world; he’s just about to reach out a grasp it and that’s the end of his career. I think that’s wonderful – I’d love to go out like that!’

We can talk about going-out later; we should discuss McCabe’s coming-in first. Was this prestigious pianist a child prodigy? ‘I started composing first. There was a lot of music around. My mother played the violin in an amateur quartet. And there was a big record collection of old 78s, with a lot of repertoire. I started composing when I was five-and-a-half, and I started playing the piano when I was six. You would think you’d do it the other way around, but they decided – since I was trying to write pieces of music, which were imitations of what was around (my mother practised at home, and there was music around, so I copied the printed music) – we’d better buy him a piano and see how he gets on. It’s a very odd way of doing it, but I can never remember a time when there was the slightest doubt about me becoming a composer. Or in my mind about me becoming a pianist – other people had doubts, but I just took it for granted. There was a period when I wanted to do other things, but basically there wasn’t really any doubt.

‘The first musical memory I have is of my mother singing Schubert songs to herself. The first piece of musical repertoire I heard which made a big impact was the Brahms St Antoni Chorale Variations, which they were playing on the record player one night; I was sitting on the stairs, listening, when I should have been asleep. It only occurred to me recently that my fascination with passacaglias goes back to that experience, because it was the passacaglia above all else that fascinated me.’ Funnily enough, I confess to McCabe, it was the Brahms Fourth Symphony that revealed classical music to me, as swiftly as flicking on a switch, when I was about nine. ‘There is something so direct about those pieces, as well as this terrific sense of structure, which is just there, and I think that had a big influence on me.’ Funny, too, that the passacaglia is a form that just seems to go on and on, suiting the purposes even of the serialists. ‘It’s a fascinating form. I’ve always loved variations, and that’s what a passacaglia is. Playing with notes – very English! And German. That’s not to say that other people can’t do it, but the English and German traditions are particularly keen on it.

‘The first musical memory I have is of my mother singing Schubert songs to herself. The first piece of musical repertoire I heard which made a big impact was the Brahms St Antoni Chorale Variations, which they were playing on the record player one night; I was sitting on the stairs, listening, when I should have been asleep. It only occurred to me recently that my fascination with passacaglias goes back to that experience, because it was the passacaglia above all else that fascinated me.’ Funnily enough, I confess to McCabe, it was the Brahms Fourth Symphony that revealed classical music to me, as swiftly as flicking on a switch, when I was about nine. ‘There is something so direct about those pieces, as well as this terrific sense of structure, which is just there, and I think that had a big influence on me.’ Funny, too, that the passacaglia is a form that just seems to go on and on, suiting the purposes even of the serialists. ‘It’s a fascinating form. I’ve always loved variations, and that’s what a passacaglia is. Playing with notes – very English! And German. That’s not to say that other people can’t do it, but the English and German traditions are particularly keen on it.

‘The thing about my childhood was that I didn’t go to school until I was eleven because I was ill all the time, and the reason I was ill is because I fell in the fire when I was nearly three. You know this business that every artist should have some real tragedy in their life? I had mine, and it was fairly dramatic, because there was nobody in the room. It was a domestic fire. There was an enormous fireguard, one of the biggest I can remember. Nobody else had one that big, but I climbed it and fell in this fire with nobody in the room. I don’t remember this – it’s all what I’ve been told – but I do remember in my thirties that the scars on my chest were still healing, because every now and then the skin would have a little irritation there.’ So he very nearly met his death? ‘Oh yes, absolutely. Vast areas of skin were burned off. I was too ill to be moved to hospital and it was wartime – no anesthetics. We had a wonderful family doctor, Charles Garson, an Indian doctor, who came round four times a day if he was passing on his way to another patient; he’d just pop in and see how I was. He kept me mildly drunk on cider for several days, as an anesthetic. That probably explains a lot! Of course, my resistance to infection was completely destroyed and I got anything that was going. When I did go to school at eleven, I was ill every week for at least a day, and in the years before that, I had everything: I had meningitis and mastoiditis at the same time, and I went deaf in the right ear. I had an operation, and the scar tissue healed over – though it actually blew off a couple of years ago: I had a sudden hearing loss and I’ve got a hole in the eardrum now. I had pneumonia several times, I had everything – and I had a wonderful childhood because I didn’t go to school! I was at home all the time, and when I wasn’t being ill I was listening to music. I had tennis lessons to help build up my strength, so I was playing tennis in the back garden. And I had lots of friends – all the local kids would come round. Somebody once wrote that I had an isolated childhood, but no! All my friends came to me, and as it happens, although we weren’t very well off (my father was a scientist but he wasn’t very well paid; we rented the house), we had a long garden. It was great: I could listen to all these records and so I got to know the repertoire when other kids were learning maths. Of course, I had a private tutor to help me pass the 11-plus, as it was called.’ And this freedom allowed him to get on with writing his own music, I suppose. ‘Yes, I wrote a huge amount of music. Very, very bad – I had no idea about technique. But one of the things I did, which I still think was the right thing to do, was I wanted to write symphonies and concertos. So I wrote symphonies, big piano pieces, collections of short pieces (not just one short piece but collections!). The symphonies were terrible: I would have six horns playing in unison throughout, fortissimo. And they would last an hour! The first symphony, as it eventually became, was in fact four symphonies put together as the four different movements of ‘Symphony No. 1’ because I decided it wasn’t long enough!

‘I stopped when I was about eleven because I realised I didn’t know anything about technique. When I was about seven or eight, I had gone to a local organist by the name of Frederick H. Wood, who came along and said to my parents: “Well, of course, what he ought to be doing is not writing these big pieces, these symphonies and things; he should be learning the technique of composing by writing minuets in the style of Handel”. That was the conventional approach for a young composer: first, you should write in the style of Handel, Bach, and so on (some people think you should do it when you’re grown up as well!). And I said: “No, I don’t want to do that – I want to be myself and do what I want to do”. And I think I was right: I knew I had no technique and didn’t know what I was doing, so I stopped until I had found out what I should have done. But in the meantime I had got used to the idea of writing big pieces, so it was perfectly natural for me to write big pieces when I had done the harmony and counterpoint – what VW used to call “the stodge”’! He said: “You must know your stodge”’ – and he was quite right: You can ignore it but you should know it first. People tell me the best way for a young composer is to learn the classical technique and I say: “No, I don’t agree – you’ve got to learn to be yourself as soon as you can, even if you can’t do it, because it will show you what you’re really interested in doing later on. And you don’t have to seek around to find yourself: you already know who you are”. Assuming you have something worth saying, that is? ‘Well, there’s nothing you can do about that! Either you’re going to say something or you’re not. All the technique is there to help you say it if you’ve got something to say, and if you haven’t, then it’s just technique – but at least it’s technique. Composers these days have pretty good techniques, despite the fact that you can do virtually anything you want, anyone who’s any good develops real technical skill at putting the thing together whatever the style is.’

How old was McCabe when he downed pen and upped book? ‘Eleven, just starting going to school, which may, of course, have contributed to that. I got interested in cricket, particularly, and films. I took up composing again when I did A-level music, which I had to do out of school hours because, although we had a music master and music lessons, the school was not geared up to teaching A-level music and the headmaster didn’t approve – he tolerated our biennial concert (which was run by a chemistry master) but he really didn’t think that music was a suitable subject for an entrant to take, or for A-level, even. My mother went to persuade him that it was a good idea for me to switch in my second year of sixth form from French, which I wasn’t getting on with, to music. He said: “What’s the point in taking music? There’s no career in that – he might as well study Hindustani or shipbuilding!” She said: “A lot of people are musicians; I know a lot of musicians”. Anyway, I got leave to do it but I had to take the lessons out of school, privately. Harmony and theory being part of that, I started to learn some of the rudiments. And as soon as I started to learn some of the rudiments, I started composing again, with much more idea of how to, even if it was still rudimentary. And needless to say, the first thing I started doing was a set of twelve-tone variations for orchestra – but I didn’t get very far!’

When did McCabe acquire a voice that he could recognise as his own? ‘I don’t really know – that’s a terribly difficult question to answer.’ Well, in the sense that Busoni, for example, acknowledged the Second Violin Sonata, Op. 36a, as his first mature composition. ‘It was fairly early. There isn’t one particular piece. There are pieces like the Variations for Piano, the 1963 set, which has been done a lot. I regard that as a very typical piece, but it’s very strongly influenced, and there are slightly earlier pieces which are influenced by other composers, but there are bits in them which are just me, I think. Around about 1962 is roughly the period in which I began to find myself.’

Does McCabe, like Rachmaninov, Busoni and countless others before him, find a dichotomy between his career as composer and his activity as pianist? ‘They have to dovetail for practical reasons, because of pressure of time, but I try to keep them separate because there is a totally different attitude to music according to which discipline you’re pursuing. I don’t analyse pieces and don’t read about them until I’ve learned them, because I feel that if I have to read about them, I really don’t understand them to start learning them. I very seldom get any surprises when I do read about them, but nevertheless you do read analyses of them. Now, when I’m writing a piece of music, the last thing I want to do is analyse it. I reckon that that happens subconsciously, as part of the process, and you’re assessing it with a kind of analytical mind in terms of the balance of instrumentation at any given point, the balance of the structure of the entire piece….’ Does he not plan the structure before sitting down to compose a work? ‘I usually write the end of a piece first, not to work backwards but to know where I’m going to, which I think also helps this entire process.’ Doesn’t this method pinion his imagination slightly, prevent the material dictating its own direction? ‘No! I have changed the ending sometimes – it’s not there not to be changed if I find that it’s not right – but I do like to know where I’m going.’ McCabe’s approach provides an interesting contrast with two British symphonists of an older generation: Simpson again, who used to say that he let his material evolve as it dictated, and Edmund Rubbra, who once told me that the most difficult part of composing for him was to get started – once he had found the right material, it would develop on its own. ‘I agree with that. The difficulty I find is getting the first note. You’ve got twelve choices: Which one should it be? And sometimes you don’t know. Sometimes you do, as in Of Time and the River: I always knew that was going to be D. And in the Second Violin Concerto I always knew that was going to be F sharp: it is was part of the sound that it had to be in that register. But in other pieces I find that I really have to struggle. I may have a few sketches for the piece and I quite often write the beginning early, but I can’t write it until I’ve got The Note.’ A single note rather than a texture? ‘The texture might be the starting point, it might even be a verbal description of the texture, it might even be three chords (the Second Piano Concerto started with three chords), but when I get down to write the piece, defining the first note I find increasingly difficult most of the time. Not always – sometimes it just chooses itself. It seems to have no relation to whether the rest of the work flows easily or not or, indeed, the relative quality of the work. It might just be a misty day and you can’t quite find where you are.’

Composers who are good pianists tend to compose less at the keyboard than composers who are only halfways competent. So does McCabe, an absolutely natural pianist, use his instrument to help him write? ‘Totally not. I only touch the keyboard once I’ve written a substantial amount of music to check through that it is actually the right notes!’ Another of the outstanding contemporary composer-pianists, Ronald Stevenson, explained to me once that the geography of the keyboard can sometimes seduce the music into directions it doesn’t really want to go. ‘Oh yes, it does – that’s exactly it. And if you’re playing a lot, and particularly if you’re playing a lot of music near your own time, you’ll also find yourself being influenced by what you’re practising. That’s one reason I try to keep the two things separate. I remember learning the Copland Variations and being terribly influenced by it for a while. That was even when I was writing away from the piano. When I found out that I was doing that, then I watched it.’ So does he try to keep one chunk of time for composing and another for playing? ‘Yes, as far as possible, which it isn’t always. But in any case I’m not doing as much playing these days. It’s not because I have certain periods of the year that I keep for composing or playing; it’s just simply that deadlines happen to fall that way. When I wrote Edward II, I did only give one recital in an eighteen-month period, deliberately. I was writing Of Time and the River in the same period. And that recital was part of a course I was teaching anyway, at Cincinatti University; I spent three months there. That was great; I thoroughly enjoyed it. I was doing some composition teaching, I was giving lectures – 26 lectures in three months, which is quite a lot. The rest of the time I was in an apartment immediately opposite the school with my laptop computer, writing away like crazy. And that’s all I was doing; I was concentrating on composition. I found that period of eighteen months very rewarding, since I was able to concentrate on the one thing, and that taught me that, as far as possible, keep them totally separate if you can. It’s worked pretty well since. And it’s so refreshing to get back to playing.’ Like coming across an old friend? ‘Yes, it is – and then I can’t wait to get back to composition when I’m playing, and when I’m composing I can’t wait to get back to the piano….’

Composers who are good pianists tend to compose less at the keyboard than composers who are only halfways competent. So does McCabe, an absolutely natural pianist, use his instrument to help him write? ‘Totally not. I only touch the keyboard once I’ve written a substantial amount of music to check through that it is actually the right notes!’ Another of the outstanding contemporary composer-pianists, Ronald Stevenson, explained to me once that the geography of the keyboard can sometimes seduce the music into directions it doesn’t really want to go. ‘Oh yes, it does – that’s exactly it. And if you’re playing a lot, and particularly if you’re playing a lot of music near your own time, you’ll also find yourself being influenced by what you’re practising. That’s one reason I try to keep the two things separate. I remember learning the Copland Variations and being terribly influenced by it for a while. That was even when I was writing away from the piano. When I found out that I was doing that, then I watched it.’ So does he try to keep one chunk of time for composing and another for playing? ‘Yes, as far as possible, which it isn’t always. But in any case I’m not doing as much playing these days. It’s not because I have certain periods of the year that I keep for composing or playing; it’s just simply that deadlines happen to fall that way. When I wrote Edward II, I did only give one recital in an eighteen-month period, deliberately. I was writing Of Time and the River in the same period. And that recital was part of a course I was teaching anyway, at Cincinatti University; I spent three months there. That was great; I thoroughly enjoyed it. I was doing some composition teaching, I was giving lectures – 26 lectures in three months, which is quite a lot. The rest of the time I was in an apartment immediately opposite the school with my laptop computer, writing away like crazy. And that’s all I was doing; I was concentrating on composition. I found that period of eighteen months very rewarding, since I was able to concentrate on the one thing, and that taught me that, as far as possible, keep them totally separate if you can. It’s worked pretty well since. And it’s so refreshing to get back to playing.’ Like coming across an old friend? ‘Yes, it is – and then I can’t wait to get back to composition when I’m playing, and when I’m composing I can’t wait to get back to the piano….’

McCabe seems to have remained remarkably faithful to the traditional genre of symphony and concerto – because they were commissions or because of the appeal of the form itself? ‘They’ve been commissions, but they were things I always wanted to do: I wanted to write symphonies when I was a wee thing. I think the symphony orchestra is a wonderful instrument, an absolutely marvellous instrument. I also think the piano’s a great instrument, with a truly orchestral range of colour, which some pianists – like Richter, for instance – really exploited. As far as forms go, I think there is still a great deal to be said in forms which have apparently been established. You change them as you want: I’ve never written a symphony in four movements; one of my ambitions is to write a symphony in four movements, with a scherzo and a slow movement, because I’d like to try it, but I haven’t had the idea for it yet. But I’ve also got the view that in many art forms if you take a framework which is one way or another is established, you can do so much within that with greater ease and complexity than if you have to create the form yourself. I always instance the western film (not the western novel, which I don’t particularly like). You can do so much within that because the parameters are laid out; you can also stretch the parameters, as someone like Sam Peckinpah did, and even John Ford: he took the set parameters, but what he did within that was so individual, in terms of portraying society, that they became quite often non-westerns. They have one or two standard scenes because that was the plot. But My Darling Clementine was about the society. And Shane, for instance, is a film about growing up. It’s a beautifully understated triangular relationship between the three adults on the little farm, and nothing is said about the attraction of the woman for the stranger and her sense of loyalty to her husband, nothing is said at all. And yet this is done as clearly and as subtly as it is in any full-length film exploring that one relationship. You can do that in a western because the form is given to a greater or lesser extent, so within that you can do so much. And the same is true of a form like symphony or concerto. I’ve written a lot of concertos and I find it a fascinating form because, on the one hand, it’s chamber music; on the other hand, it’s a dialogue between the orchestra as one entity and the piano as another. Again, it could be a battle between the two. It can be something which has a totally different connotation, like Bernstein’s Age of Anxiety, which I still think is one of his best works and doesn’t fit into any of the foregoing. There’s so much you can do with that one form, so I don’t think it’s necessary for me to invent a new form. Nobody’s invented a new form for orchestra anyway. There hasn’t been any such thing for 150 years. Once the symphony and concerto and the short orchestral piece were established, that’s it. And they’ve changed out of all recognition. They’ve evolved.’

And what of the evolution of McCabe’s own style? ‘I think it’s got more complex (I must be careful to distinguish between complex and complicated, because complicated is not good). During the ’60s I developed very much in certain directions in the way of handling the orchestra. I was evolving my own particular style of orchestrating, but I’ve always been receptive to other music, so I keep changing the emphasis of what I listen to for pleasure and what interests me.’ So how, first, would he characterise his style of orchestration? ‘Very much block orchestration: The brass as a big band, really – I used to enjoy big-band jazz very much, and still do: Count Basie, Gil Evans and so forth, that kind of band. The woodwinds as a block, the strings as a block. And although I would then mix elements in, because I do enjoy orchestrating very much, nevertheless that is still, I think, a characteristic of my orchestration. But I’ve got much more interested over the years in layers of things happening at one time. In the Third Symphony particularly, for instance, there are various layers of things all happening at the same time, maybe even apparently at the same tempo – not in reality: there are two tempos going on at once. It got more complex as time went on, I suppose partly because of being more confident about handling the resources available to me. And the influence of other musics, like, in recent years, I’ve got very much more interested in William Byrd and I’ve given a lot of performances of his music on the piano and played lots of choral CDs of his. I’ve rediscovered Bruckner, which I’m sure had a big effect on Of Time and the River – it wasn’t an instant thing, it was a period of several years when I rediscovered Bruckner after not listening to him for a long time. Things like that change your emphasis. And that is how the music changes.

‘And also things like landscape is important to me. I’ve written a lot of pieces inspired by different kinds of landscape. Australia has inspired a lot of things. And I do find that I respond to external stimulus sometimes in a very immediately way, so that affects what you write: The sound of the music is affected by the stimulus. If it’s a desert, you’re obviously going to write a different piece than if it’s the Lake District.’ Deserts are things that fascinate McCabe, and seem to exert a potent influence on his music. ‘Yes, they do – always have.’ Why? ‘I don’t know. That goes right back to childhood again. Two things. First of all, Scott of the Antarctic, the film, and the diary of the last expedition, which was given to me as a child. I found that a terribly moving and exciting story. The idea of this great desert – because the Antarctic is a desert – I found fascinating, this enormous expanse of nothing-but-something; very important. And then, when I was still a child, I read a diary of the Burke and Wills expedition across Australia (this is one of the reasons I’ve been fascinated with Australia), and I was hooked on that. Apart from the similarities of the story, it was the extraordinary quirks of fate that meant they died instead of being found, by about a quarter of an hour or eleven miles; the parallels really are quite extraordinary. Again, it was the description of the landscape and this sense of the enormous courage and heroism of these people in that landscape, despite all their failings as human beings, I found inspiring. Deserts, whether of snow and ice or of sand, just became something I was fascinated with as of childhood, and sooner or later it was bound to come out in the music.’ Is it the concept of man against the desert or the idea of the desert itself that McCabe finds compelling? After all, there’s more to look at in a rainforest than in a desert. ‘Oh yes, there is. I don’t think it has to do with man in that environment; I suppose, being a human being, it is to do with man because it’s one’s response to it, and that must be a part of it, but I’m not conscious of that. All I’m conscious of is a fascination with this vast expanse. I once did a British Council recital tour in the Middle East in various places you wouldn’t go to these days (Baghdad was one of only two places I’ve ever heard gunfire, and it was relatively quiet at that time!) and I was taken out into the desert a couple of times. I had never realised that yellow was a colour with such variety. I daresay you get tired of it after a while, but I was three weeks in the Middle East and looking at yellow most of the time, and I never got tired of it. I found it really quite extraordinary; it’s not my favorite colour. There is such richness and diversity within something which seems so limited you can’t imagine there’s anything else, and yet there’s such extraordinary variety. And, of course, the desert itself is changing all the time.’

McCabe’s raising the question of colour prompts a question about colour in his own music. He has just described his orchestration as using instrumental block; is colour something that is becoming more important to him? ‘I think it always was. There’s a bit in the penultimate variation of the Hartmann Variations, which was my first big success orchestrally (it was done a lot at one time), where the variation of the theme itself is heard on vibraphone and solo double-bass in harmonics (I can’t remember what’s happening in the background), and it’s a wonderful sound! I don’t know where I got it from, but it works like a dream, provided that the bass player can play it because it’s a very difficult thing to do. Weird touches of colour like that did creep in even in those early days; that was 1964. I’m fascinated by the way a harp harmonic will change the way of a horn note or a clarinet note, or the way two each of clarinets and bassoons will make an extra couple of horns.’ Such little touches can be extraordinarily effective: I remember at the sessions for Czesław Marek’s Sinfonia (on Koch Classics) noting with amazement how Marek’s adding a pizzicato viola note to a combination of harp and clarinet changed the entire texture, suddenly giving it a luminous, bell-like quality. ‘The viola is a very good instrument for doing things like that. I do like the subtleties of colour that you get; that’s one of the reasons I find Debussy and Ravel so interesting, because their sense of orchestral colour is so marvellous.’

McCabe’s ballets – The Teachings of Don Juan (1973), Mary, Queen of Scots (1975), Edward II (1994–95), and the two, based on Arthurian legend, with which he is currently engaged – suggest that he particularly enjoys writing music to dance to. Was ballet a long-standing ambition, or did these works occur simply because he was asked to write them? ‘It wasn’t something I particularly wanted to do, but as soon as it was suggested, I thought, yes, I’d love to do this. You always have to have a positive response anyway. The first full-length ballet, Mary, Queen of Scots, in the mid-70s, I enjoyed doing enormously. It’s never been revived, though I thought it was a very good ballet; I enjoyed it. When it came to Edward II, it was David Bintley who suggested the subject, and as soon as I read his draft scenario, I thought, yes, this is absolutely wonderful. The reason was that I could see immediately that this was about people whom I felt I could learn to understand. Edward and Isabella became real people to me; I feel very involved with them. That’s what I like about ballet. I much prefer to write ballet; I don’t want to write opera, and I think I’m too old to start. I’ve done opera before but not grand opera. I can’t think of anybody who started writing opera properly late in life and was successful; it something you really have to get into in your twenties, thirties, and persevere with. The great thing about ballet is you don’t have the words to worry about, you don’t have to worry about balance with the orchestra, you don’t have to worry about the actual words – and words are very specific no matter how many meanings they may have. And in ballet you can do what you like. You’re dealing with human beings and you’re relating to them through the music, as you would in opera, but you don’t have these extra things to worry about. It’s more direct. There are certain things you have to do, like you have to have some idea of how long each section or number should be, but don’t you have to do that anyway? In a symphony you have to know roughly what the proportions should be. So I don’t see a lot of difference between that and writing abstract music, except that it’s about specific people who are, one hopes, intelligible beings.’

Let’s now move on to the Fourth Symphony, Of Time and the River. What is the significance of the title? ‘Actually, the title only occurred to me as I was finishing off the score. It was going to be Symphony No. 4, which I don’t call it, by the way; Novello’s do, but I don’t. I don’t mind; I can understand why. It’s the book by Thomas Wolfe, the earlier Thomas Wolfe [who died in 1938, at the age of 38], not the Bonfire of Vanities Tom Wolfe, and it’s a semi-autobiographical novel of some thousand pages – wonderful book. The thing that fascinates me about the book is that time and travel are very important in it, and a lot of the travel is railway journeys down long rivers…. Good heavens!’ McCabe suddenly stops as he notices the song played as muzak in the restaurant where we’re having our conversation. ‘That’s Mel Torme, Coming Home, Baby; you didn’t expect me to recognise that, did you? Anyway, back to Of Time and the River. Most important of all is that sense of time and travelling. At one point in the book he refers to that business, you know, when you’re in one train and there’s another train by the side of you and because of the different speeds you’re going at, you seem to be going backwards, although you know you’re not. I started thinking that this is so applicable to this piece, because it’s got a very strong tonal scheme, in a cycle of fifths, from D to A flat and then from A flat back to D (not original, I know, but it seemed like a good idea at the time!); it was something that I wanted to explore very rigorously. The fifths are landed on not in a very carefully worked-out order; again, it’s a question of the proportions being right as they seemed to me, so one key centre doesn’t last for very long and another one does. So there is a kind of tempo of key-centre changes going through the piece. And also (this was the very first thing that occurred to me) I wanted to write a piece in two parts where the first part would get slower imperceptibly and the second part would get faster imperceptibly. I found getting faster much easier; getting slower was very difficult, and since arithmetic was never a strong point I ended up with some very peculiar and incorrect metronome marks.’ He can blame it on all those math lessons he missed as a child. ‘Yes, that’s right! It was quite an education finding out that it’s easier to get quicker imperceptibly than it is to get slower. People are only aware in some circumstances that the gear-change has already occurred.’ Which he effects through overlapping metres? ‘Yes, so that a group of four notes then becomes four out of a group of six per beat, so the beat is longer but the pattern of four notes is still going and it’s crossing the beat for a while, until the new beat has been established in the bass. But you don’t notice that it’s being established in the bass until after a bar or so, when you think, hang on, we’ve actually got slower, haven’t we? That was how the whole piece started, with those different tempos. It’s a Sibelius thing really, I suppose, or Brahms to some extent: different tempi going on at the same time, a very elaborate tonal-centre structure, and also the idea (very much like Nielsen’s Fifth, although I wasn’t thinking of that at the time) of a very positive D and a very negative A flat (the Fifth Symphony has F positive and B negative).’

It’s probably a silly question, but does McCabe see his music evolving towards some particular goal – is there, say, some quality of language he’s trying to capture? ‘No. It evolves, and changes slightly from time to time, but I haven’t got any particular goal. There are pieces I would like to have written and others I probably will, and there are pieces I’d like to play which I certainly never will now.’ So he doesn’t have plans for some crowning Choral Symphony or anything like that? ‘Yes, I do! I wanted to write a Pastoral Symphony, and I got very near a commission for it. Not in F major. This would be specifically about man’s relationship with the environment. I’ve been an environmentalist ever since about 1947, long before the word was coined, when I first went to the Lake District on holiday and fell in love with the place, and felt a strong sense of being at home in one particular area; I’ve been back many times since, though not for some years. That gave me a concern about areas like that. That’s why I wanted to write this piece, and I got quite a lot of poems marked up for use in this. I’ve got another thirty years of composing ahead of me, so it might happen!’

Hope it’s OK for me simply to say that I find this an entrancing piece of writing that has me looking forward to whatever Toccata can do about CD-ing John McCabe’s hidden empire. Entrancing because the approach is so varied – musical evolution, influences, intentions, methodology and so on. To read anything with mentions of Racine Fricker, Alan Rawsthorne, Tippett and Karl Amadeus Hartman, not to mention RVW, Bax & Walton, sends me into intellectual/emotional overdrive. I wonder if I’m the only person south of The Wash who can whistle the opening of Rawsthorne’s 2nd Piano Concerto at the drop of a hat! In the Good Old Days my father took me to a Friday Prom to listen to Campoli playing the Beethoven – this was when Friday night was Beethoven + something ‘modern’ – he marched me down from the gallery in the middle of what may have been the first performance of Fricker’s 1st Symphony; I often listen to it now to try to figure out what finally got my father’s goat, as it were. I’m what they call a ‘polarity responder’, so his reaction to this splendid piece was one of the things that finally got me switched into ‘Contemporary Music’. I first heard Hartman’s 3rd Symphony through headphones on an ancient crystal set from ‘Hilversum’ one Sunday afternoon back in the early fifties. I was attracted to this composer largely just because of his evocative name to start with. Then I found McCabe’s Hartman Variations which are a real dream. Thank you, Martin!