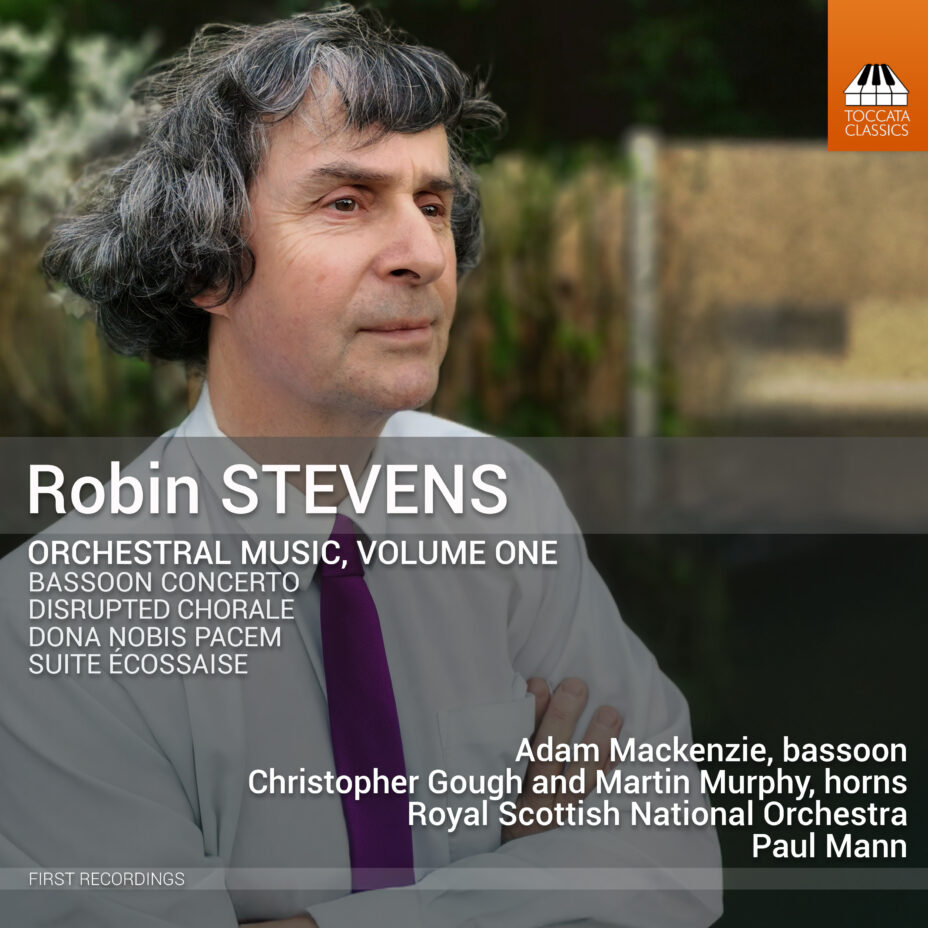

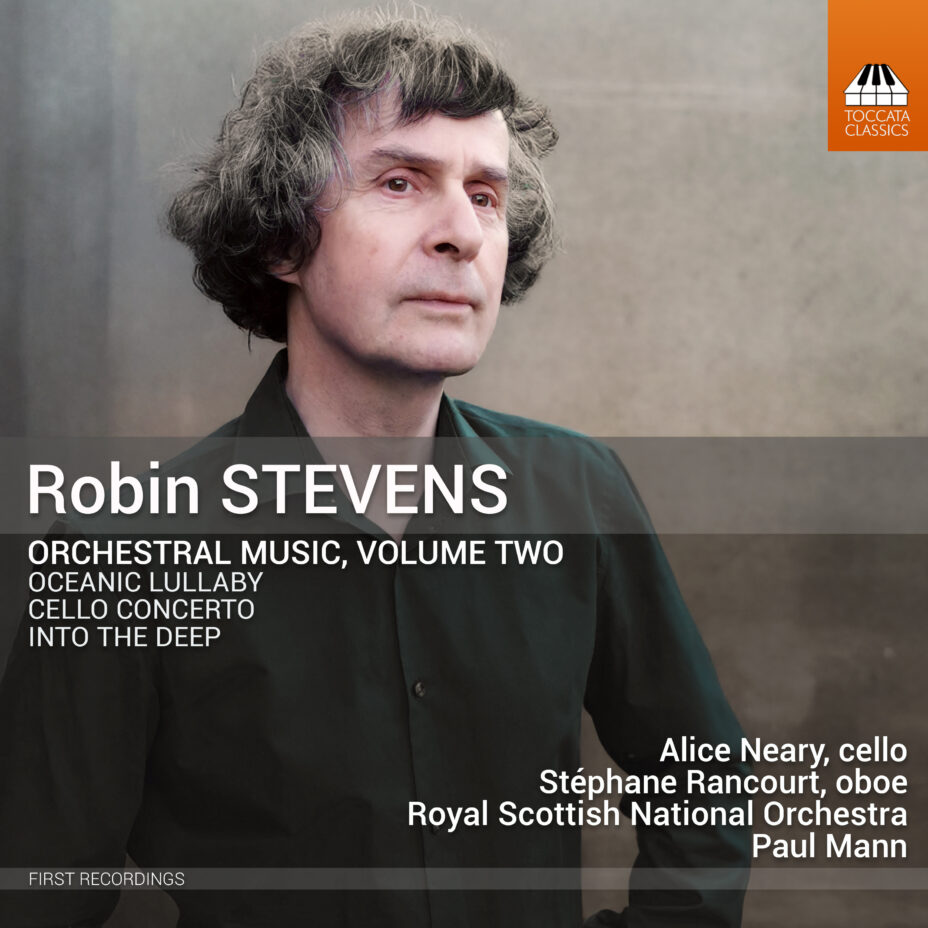

The news of the death of the composer Robin Stevens earlier this week (on 16 February) did not come as a surprise: Robin had been diagnosed with cancer of the colon some years back, and the disease had been spreading through his system since then. Robin, who was born in 1958, had not had much public attention as a composer, and the news of his imminent demise seems to have galvanised him into making sure that his music might survive him: he organised a five-album project to record his chamber music on Divine Art, and he came to us at Toccata Classics do the same for his orchestral music – a series of three albums, each with shorter ‘satellite’ works grouped around a major concerto, one each for bassoon, cello and viola. You’ll find Volume One (which was released in January) here and Volume Two (scheduled for March) here, and Volume Three is in preparation – we wouldn’t normally bring out two major orchestral releases by the same composer so close together, but we wanted to give Robin the satisfaction of holding the CDs in his hand and knowing that his music would outlive him in these recordings. And we just made it: Vol. 2 was delivered to him two weeks ago.

The sessions for all three albums were held in Glasgow last summer, with the Royal Scottish National Orchestra in top form under Paul Mann. At the beginning of the year Robin was far from certain that he would live long enough to attend the recording sessions, but in the end he lived far longer than he had been given to expect. The managing of this major project has involved a lot of people – the musicians themselves, of course, but many others in ‘backroom’ roles, all of whom were aware of the urgency of the task in hand. And it involved Robin himself, of course: we were often on the phone several times a week. Robin was one of nature’s worriers: he was always suspicious that things might go wrong. But once he trusted you, that was it: he accepted your judgement and was content with it. Like many composers, he found it a bit of a wrench to pass his music on to someone else, but once he realised that Paul Mann knew his scores backwards and had mastered their complexity, he relaxed – and in the end he dedicated his last major work, the symphonic poem Into the Deep (to be heard on Volume Two), to Paul as a token of gratitude. Into the Deep began life as the intended slow movement of a projected symphony, but as he was writing it, Robin realised that he no longer had the strength to tackle such an ambitious work, and so decided that Into the Deep could stand on its own. It is indeed deep – and it’s pointless wondering what a Stevens symphony would have sounded like: Into the Deep has enough emotional power to occupy the listener’s mind on its own. A degree of acceptance, too, characterised his attitude to his disease: he knew there was nothing that could be done about it, and he talked about his state of health almost as calmly as he might discuss the weather, even when his voice began to betray his infirmity.

The recorder-player John Turner is a mainstay of musical life in Manchester, where Robin lived, and it was John who suggested that Robin write an autobiography, which can be found on his website. It was John, too, who suggested that Robin contact us at Toccata Classics and, sad though I am to see him finally succumb to his disease, I’m proud to know he felt we had done him proud. Those three concertos make clear that he was a major composer – his Cello Concerto, for example, is something of a bigger, burlier, knottier cousin to Britten’s Cello Symphony – and the smaller works are atmospheric, appealing and charming by turns. Musicians interested in examining his music will want to know that it is being published by Forsyths, again in Manchester, and curious listeners now have five albums on Divine Art and three on Toccata Classics to find out what he was made of.

—Martin Anderson, 19 February 2026