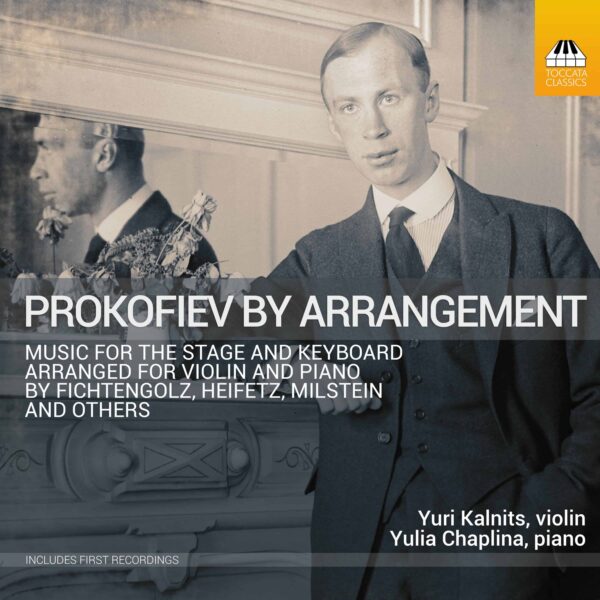

At the beginning of October Toccata Classics will release a new album, by the violinist Yuri Kalnits and pianist Yulia Chaplina, of music by Prokofiev arranged (very skilfully and idiomatically, too) for this combination. It is a real bran-tub of treats, some familiar (the March from The Love for Three Oranges arranged as a showpiece encore by Jascha Heifetz; the Waltz from the opera War and Peace) and some rarities (incidental music composed for a theatrical portrait of Cleopatra and for a production of Pushkin’s verse drama Boris Godunov that never actually saw the stage) but all impregnated with the sweet-sour spiky-beguiling flavour that tells you instantly who created them.

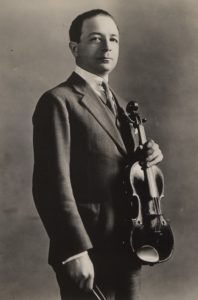

The selection embraces almost half a century of unremitting composing productivity. At one end there’s one of the first attempts (in 1901) by the precocious but untutored ten-year-old to capture the teeming ideas swirling around in his brain and his fingers. At the other is one of the last scores, the ballet The Stone Flower, still unfinished at his death. At first blush it might seem strange for a violinist to devote such care and ingenuity to music not originally written with the violin in mind, especially from a composer whose output contains such central and well-loved repertoire cornerstones as the two violin concertos, the two violin sonatas and the Five Melodies. Yet it should be remembered that all through his creative life Prokofiev relied on close and fruitful connections with collaborators across the musical, theatrical and literary spectrum whose attributes he recognised complemented his own. Several people who played an important part in igniting the creative process were violinists, in particular the Polish Paweł Kochański, the Russian David Oistrakh and the Franco-Belgian Robert Soëtens. And if any virtuoso can be credited with having put Prokofiev incontrovertibly on the world map, it must be the Hungarian Josef Szigeti who – having been serendipitously in the audience in October 1923 to hear a somewhat lacklustre first performance of the First Violin Concerto in which Koussevitzky conducted the Paris Opera Orchestra with his concertmaster Marcel Darrieux as soloist – decided on the spot that he would feature it in almost every major city of Europe and America, kicking off with the Russian premiere in the freshly renamed city of Leningrad.

Of course, there were many other musicians and creative artists whose influence and inspiration have left their imprint on Prokofiev’s music. Without the conductors Albert Coates, Sergei Koussevitzky (also a noted double-bassist) and Samuil Samosud, the cellist Mstislav Rostropovich, the pianist Sviatoslav Richter, singers Vera Janacopulos and Nina Koshetz, the impresario Sergei Diaghilev, theatre directors Vsevolod Meyerhold and Alexander Taïrov, the cinema director Sergei Eisenstein, the poet Konstantin Balmont, the philologist Boris Demchinsky, the writer and editor Pierre Suvchinsky, there would be glaring gaps among the works that make up the corpus of one the twentieth century’s most widely performed and loved composers. (No composers, notice, in this list, although an indispensable, lifelong source of encouragement and constructive criticism remained his Conservatoire friend Nikolai Myaskovsky.) Another person in whose judgment Prokofiev placed unwavering trust was his second wife, Mira Mendelson, not only for moral and tactical support in navigating (well, mostly resisting) the impenetrable thickets of Soviet cultural bureaucracy, but for the conception and librettos of his later Soviet-era operas and ballets.

Prokofiev first encountered Paweł Kochański in Kiev in April 1915 in the company of Karol Szymanowski, for whom the violinist was already as indispensable a collaborator as he was to become for Prokofiev. Eighteen months later Prokofiev, having just about completed the composition of and initial production arrangements for The Gambler, was deep into the composition of a new concerto for Kochański to premiere in Petrograd the following November along with his new Second Symphony. By September 1917 it was written, and Kochański himself had prepared the orchestral parts ‘with the utmost care and understanding’, as Prokofiev noted in his Diary. The October Revolution, of course, put paid to the planned premiere, but Kochański had also made his own edition of the solo violin part and took it with him when he left Russia in 1921 to immigrate to the United States. (He generously provided it to Koussevitzky and Darrieux for the Paris performance.) Later, in 1925, Kochański worked intensively with the composer on the version of the Five Songs without Words, Op. 35, Prokofiev had written for Nina Koshetz in 1920, which as Cinq Mélodies became one of David Oistrakh’s most frequently performed recital works. Three of the Mélodies were dedicated to Kochański, one to Szigeti and the remaining one (No. 2) to Cecilia Hansen, the violinist wife of the pianist Boris Zakharov, a close friend from Prokofiev’s Conservatoire days. Later, when after nineteen years living in the west Prokofiev had moved back to live in the Soviet Union, to the mystification and consternation of most of his friends, the two Violin Sonatas, No. 1 in F minor, Op. 80, and No. 2, Op. 94bis (the violin version of the Flute Sonata) were composed in close collaboration with David Oistrakh.

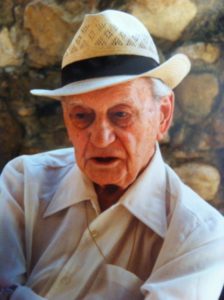

The Second Violin Concerto, Op. 63, brings into focus another violinist, less well-known to history than his colleagues, who, nevertheless, had a major if shorter-lived effect on Prokofiev’s life and work: the Franco-Belgian Robert Soëtens. The relative obscurity is unjust. In October 1997, following the violinist’s death at the age of 100, Martin Anderson’s obituary notice in The Independent opens with the statement that ‘The death of the French violinist Robert Soetens breaks one of the last links with the breathtaking flowering of musical life in Paris in the first half of [the 20th] century’. His was indeed a remarkable and indomitable life in music, highlights of which included duo partnerships with Ravel and Prokofiev (the latter being the only occasions on which Prokofiev agreed to appear as a pianist with another musician – except for his first wife, the soprano Lina Codina), collaborations with Roussel and four of the composers of Les Six: Poulenc, Honegger, Milhaud and Tailleferre. He also gave the first performance, with Samuel Dushkin, of Prokofiev’s Sonata for Two Violins, Op. 56 ̶ the concluding item in the inaugural performance of Le Triton, a Parisian society for new chamber music. Prokofiev was so impressed by the performance that he decided there and then to write a new violin concerto for Soëtens, to which the surprised and slightly overwhelmed violinist responded not only with alacrity but proposing to arrange a 40-concert duo tour of Spain, Portugal and North Africa immediately after the first performance of the new concerto in Madrid, an invitation he was no doubt equally surprised to find Prokofiev accepting.

Pride of place in the new album is an arrangement by two distinguished Israeli musicians and teachers who are both professors of the famous Rubin Academy of Music in Tel-Aviv, the pianist Viktor Derevianko and the violinist Yair Kless, of one of Prokofiev’s best-known solo piano collections, the twenty short pieces that make up Visions Fugitives. So convincing is this version that you can easily persuade yourself that the composer must have had the timbre and cantilena of the violin at the back of his mind all the time. Here is a little background to the genesis of the original composition, and how it got its name. In June 1915, as Prokofiev’s diary records, ‘I sat down at the piano and decided to write some little squibs of music, “doggies” as I used to call them eight years or so ago. And the doggies started to grow incredibly easily. I liked them very much and they emerged with impeccable finish. Three of them [Nos. 5, 6 and 10 in the eventual published score] were completed in the first day. […] I decided to dedicate all these doggies to my friends’. Nos. 16 and 17 were added later that year; Nos. 2, 3, 7, 12, 13, 20 joined them in 1916, the remaining eight in 1917. ‘No. 5 was composed first, No. 19 last; the order in which they appear in the collection was dictated by artistic and not chronological considerations’, Prokofiev later recorded in his Autobiography. The title comes from a 1903 poem ‘I Know No Wisdom’ which contains the invented word ‘Mimolyotnosti’ (literally ‘Transiences’ or ‘Ephemeralities’) by Konstantin Balmont, with whom Prokofiev was much engaged at the time because of what he discerned as the particular musicality of his verse:

I know no wisdom, wisdom I leave to others, Fleeting visions [mimolyotnosti] only do I capture for my verse, In each one seeing entire worlds Filled with the fickle play of rainbows.

Balmont’s then girlfriend, one Kira Nikolayevna, a fluent French-speaker, was present one day when Prokofiev was playing the completed work to the poet to see if he found the music appropriate to the word from the poem he had chosen for the title, and it was she who came up with the poetic French equivalent by which the work has ever since been known outside Russia. Some of the pieces last less than a minute, but are a mine of hitherto unexplored piano-playing techniques. The comic right-hand punctuations of No. 10, marked ridicolosamente, even seem to anticipate the ludicrous pianism of Chico Marx featured in the Marx Brothers’ films by almost two decades.