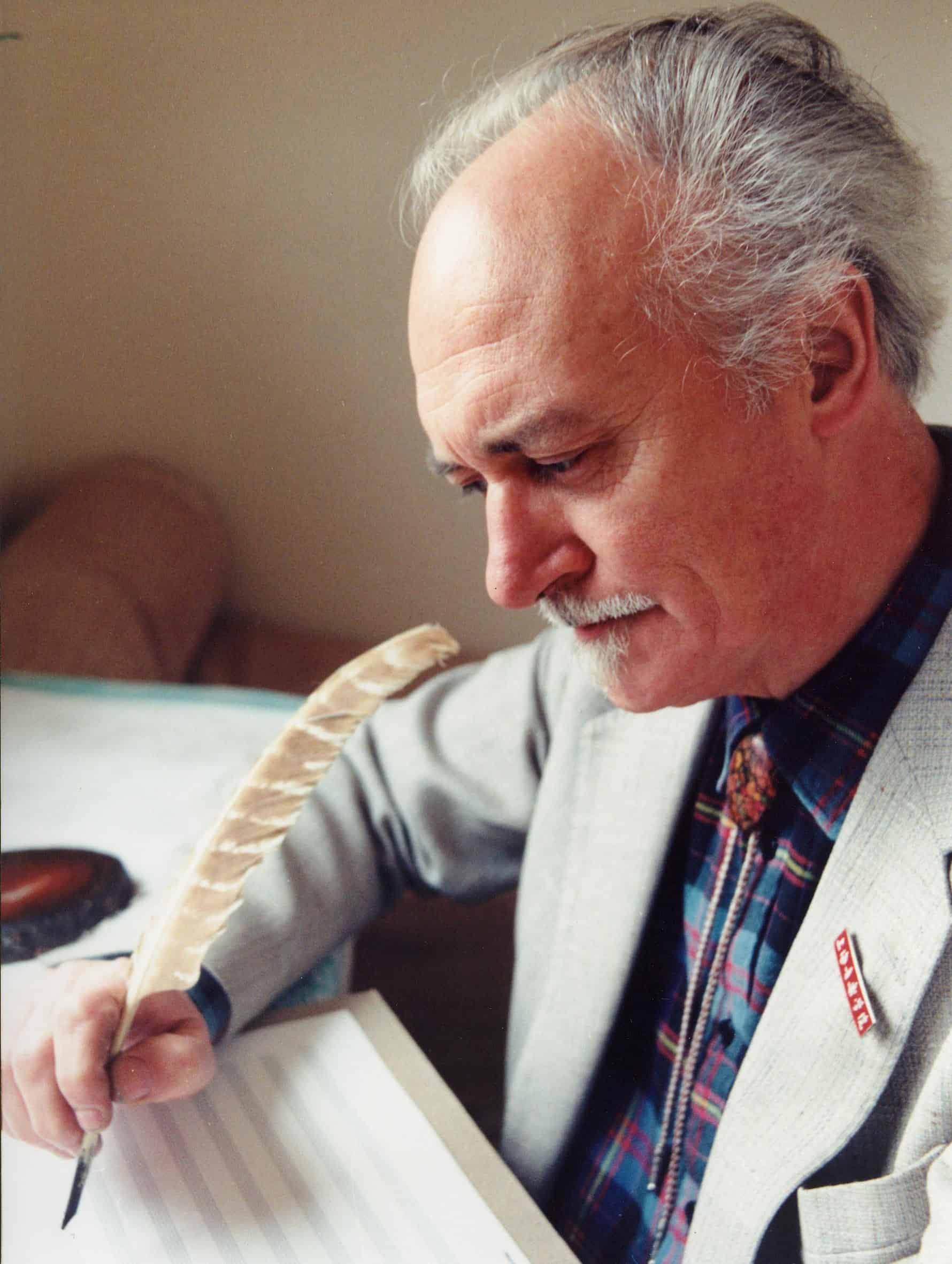

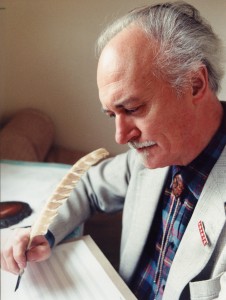

Ronald Stevenson composing, quill in hand, at the desk in his ‘Den of Musiquity’ at home in the village of West Linton below Edinburgh

This Friday, 6 March, Ronald Stevenson will celebrate his 87th birthday. In a different world, or even just a different country, one where human life was measured not in terms of income and material possessions, but humane values and the sharing of those values, this event would be celebrated on the widest of scales. His greatness of mind is equalled by his greatness of heart, able – like his beloved William Blake – to see a universe in a grain of sand and heaven in a wild flower. For a tiny example of this outlook, and of his masterly pianism, have a look this tribute to a small American cat. Stevenson’s concern, throughout his life’s work as composer, pianist and writer, has been to offer us ways of understanding the universal nature of our own humanity. His great ‘mentor in absentia’ Ferruccio Busoni wrote that music knows no border posts – that it was born free and to win freedom is its destiny. Stevenson has sought to engage with music as found in many cultures, and the term ‘world music’ is one strongly associated with him.

This Friday, 6 March, Ronald Stevenson will celebrate his 87th birthday. In a different world, or even just a different country, one where human life was measured not in terms of income and material possessions, but humane values and the sharing of those values, this event would be celebrated on the widest of scales. His greatness of mind is equalled by his greatness of heart, able – like his beloved William Blake – to see a universe in a grain of sand and heaven in a wild flower. For a tiny example of this outlook, and of his masterly pianism, have a look this tribute to a small American cat. Stevenson’s concern, throughout his life’s work as composer, pianist and writer, has been to offer us ways of understanding the universal nature of our own humanity. His great ‘mentor in absentia’ Ferruccio Busoni wrote that music knows no border posts – that it was born free and to win freedom is its destiny. Stevenson has sought to engage with music as found in many cultures, and the term ‘world music’ is one strongly associated with him.

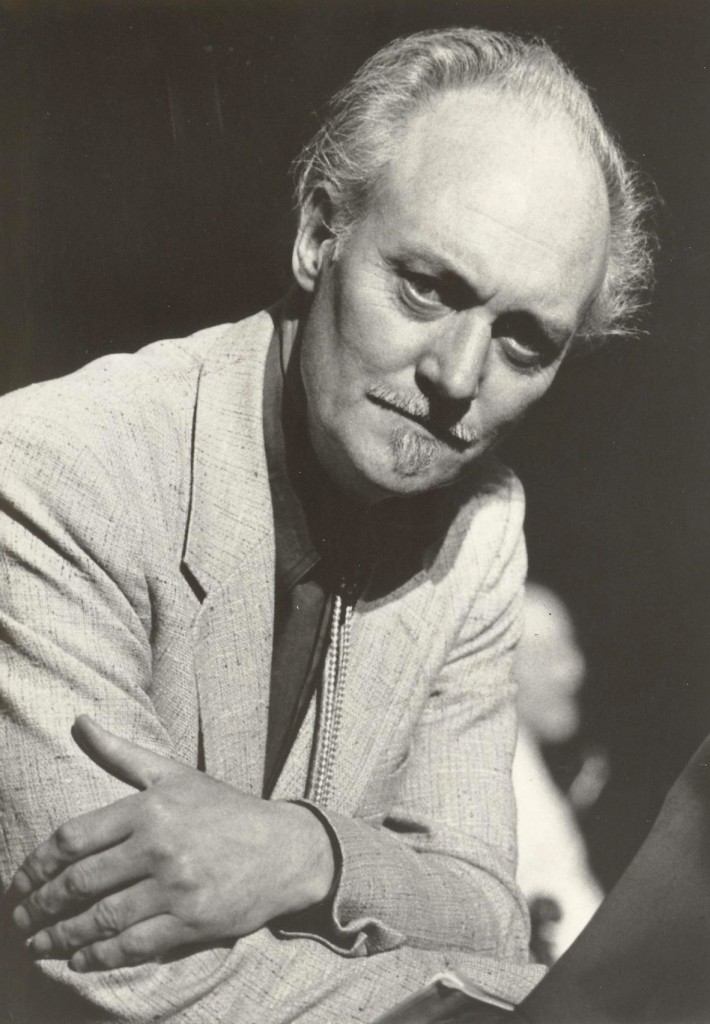

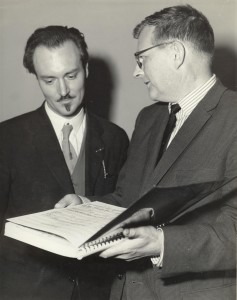

Stevenson with the young John Ogdon in 1959: they first met as students at the Royal Northern College of Music in Manchester in 1946, when Ogdon was nine and Stevenson eighteen.

For all his international importance, Ronald Stevenson has played a major role in my own life, and it is essentially a personal tribute I would like to pay here. I was a schoolboy in Banff in north-east Scotland when I first encountered Ronald Stevenson in the pages of The Listener, and then on the radio, talking about Havergal Brian and William Blake. It was through our shared interest in these two giants that we entered into correspondence, and it was the late Malcolm MacDonald who introduced me to Stevenson personally, after a recital at the Queen Elizabeth Hall in 1974. From then on, Stevenson (and his wife Marjorie) became a living force in my life, opening door after door, whether the subject was music, poetry, Scotland, ethics, political thought, internationalism, ‘unity in diversity’….

Edinburgh Festival, 1962: Ronald Stevenson presents Dmitry Shostakovich with a facsimile score of his Passacaglia on DSCH, based on Shostakovich’s initials

It was in his company that I attended Hugh MacDiarmid’s funeral at Langholm. As a student, I was able to bring about visits by Stevenson to Aberdeen, in 1977 when he performed his monumental Passacaglia on DSCH (at 80 minutes in length, it is reputedly the longest single-movement work in the piano repertoire), and in 1979 to premiere the Piano Sonata of Ronald Center, another Scottish composer who deserves more attention (and, I am pleased to say, is getting it from the young Scottish pianist Christopher Guild on Toccata Classics). Later, when I was working for the European Parliament, the Stevensons made several trips to Luxembourg, where Ronald (twice) played the Passacaglia, inter alia, and gave the premiere of his own A Rosary of Variations on Seán Ó Riada’s Irish Folk Mass, which Chris Guild has now recorded on the first of a number of CDs he intends to devote to Stevenson’s music.

It would be impossible to express the depth of my life-long debt to Ronald Stevenson. He has been the greatest single human influence on my life. Had I never known him, I would have been a very, very different and much-diminished human being. And that’s why I was proud and happy to have been able to sponsor this new CD of his piano music by my friend Christopher Guild, released in tribute to this towering figure on his 87th birthday – a tiny token of my gratitude to Ronald and Marjorie, standard-bearers (standard-setters) for a better world than the one we have.