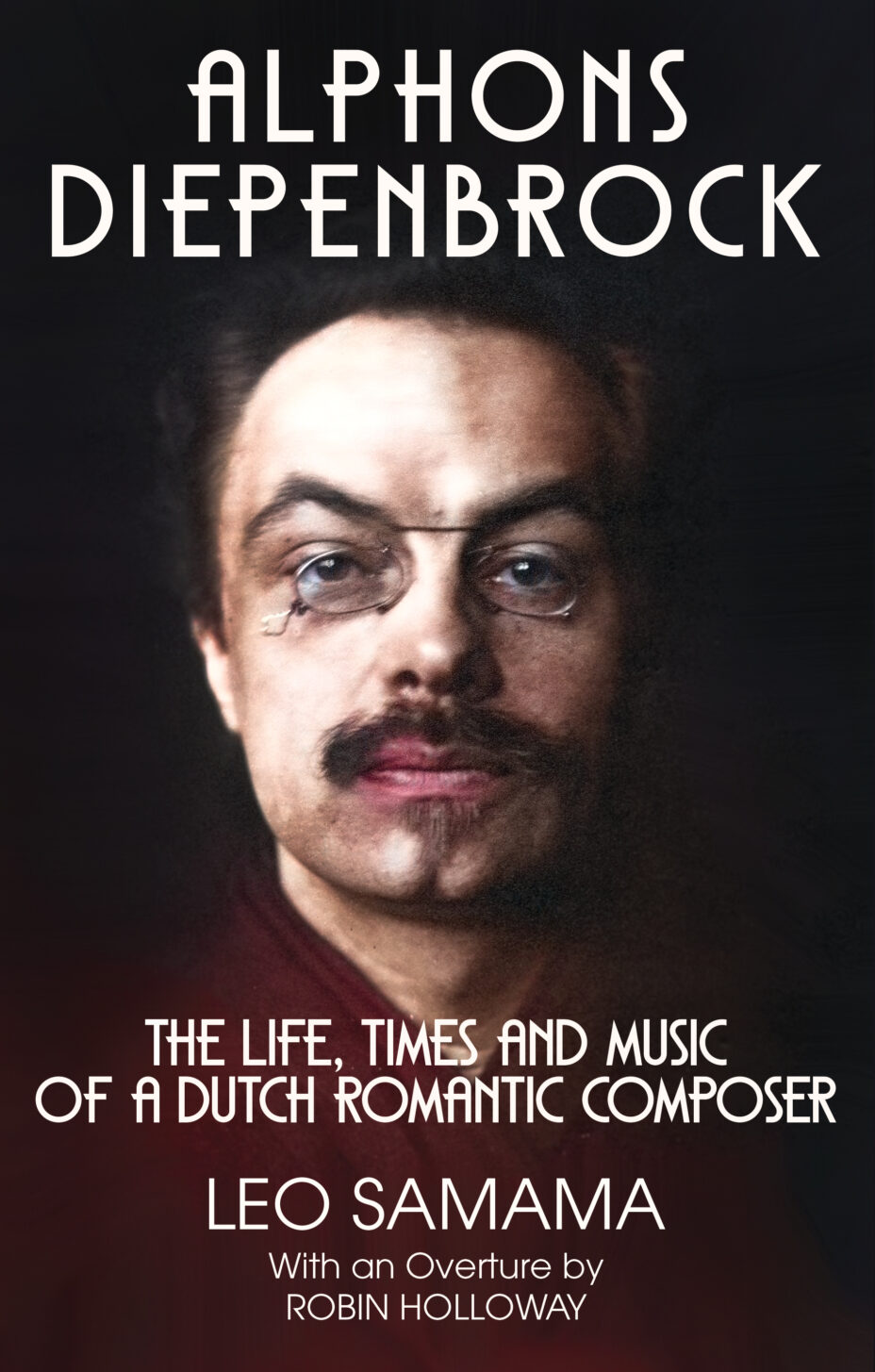

Sometimes one has the impression of having been forced by fate to write a book, to start a research, to accept a commission or venture into a new job. At least, this was what I felt the moment the Alphons Diepenbrock Foundation asked me to write a monograph on the composer whose legacy the foundation has been dedicated to for over a century. Of course, I was well aware of the music of Diepenbrock – in fact, already since as a child when I was allowed to visit the Sunday afternoon concerts of the Concertgebouw Orchestra with my grandmother and heard the symphonic suite Electra compiled by Eduard Reeser and conducted by Bernard Haitink in 1958.

My parents had just moved to the garden village of Laren, less than 30 minutes by car from Amsterdam. There, we lived only a few hundred yards away from Holtwick, the house where Diepenbrock and his family escaped the hustle and bustle of the big city, and where the composer Matthijs Vermeulen later lived with his second wife, Thea Diepenbrock, the composer’s younger daughter. And it was with their daughter, Odilia, that I cycled to our high school in Baarn for some time – alhough in those early years I was still completely unaware of her familial connection to Alphons Diepenbrock.

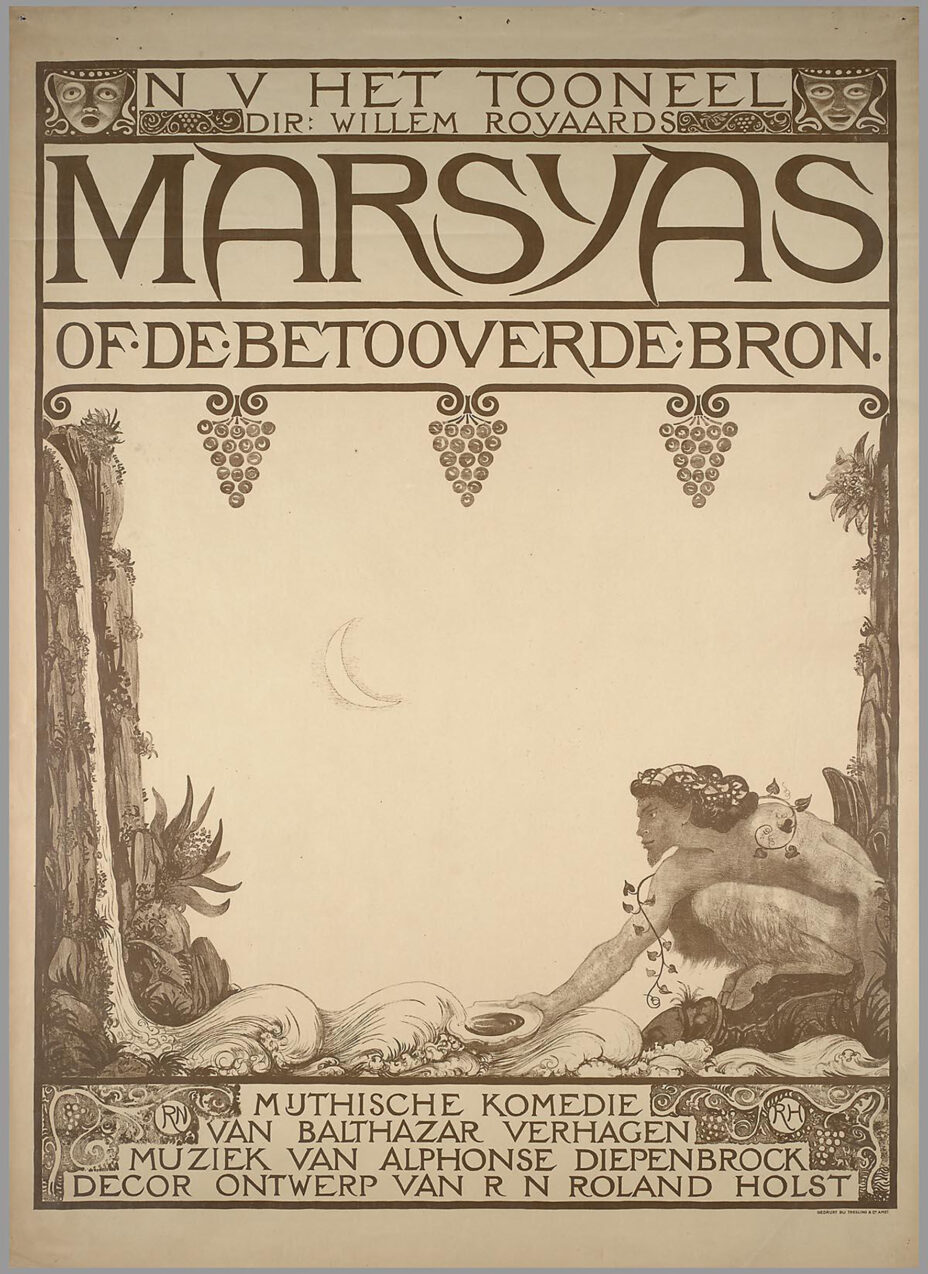

In the 1960s the Dutch music publishing house Donemus released gramophone discs with scores attached to these of the overture to Diepenbrock’s The Birds and selections from his Marsyas music, again conducted by Bernard Haitink.

Later, after having decided to study musicology at Utrecht University, I had the opportunity to study with Eduard Reeser, who was head of the department until 1973 and a renowned Diepenbrock scholar from the 1930s onwards.

During these student years and the three decades thereafter, Reeser was my mentor in musicology. Thus, the topic of Diepenbrock and his music was never far from our minds, as was Dutch music in general. When Reeser confided in me that he was afraid not being able to fulfil his wish to write, even with the support of Thea Diepenbrock, an all-encompassing biography of Diepenbrock, I could not by far imagine the Alphons Diepenbrock Foundation would ask me a decade later to try my hand on a monograph.

For Dutch music history Diepenbrock was something of a cause célèbre. He lived exactly three hundred years after Sweelinck. And while Sweelinck (1562-1621) was considered to be the last composer of the famous Netherlands schools that marked the Dutch influence on Renaissance music (as was wrongly believed until well into the last century), Diepenbrock (1862–1921) was believed to be the first internationally renowned composer after Sweelinck.

He and his generation, together with the newly founded Concertgebouw Orchestra and its conductor Willem Mengelberg, propelled Dutch music into the twentieth century, attracting the attention of a large international audience. And the fact that Diepenbrock himself was an adamant adversary of the ‘bourgeois’ music of the nineteenth century, such as that by Johannes Verhulst, was considered as enough proof that he was as one of the first Dutch composers searching for newer means of musical expression, at first partly based on Wagner’s examples, and later on the music of Mahler on the one hand and that of Debussy on the other.

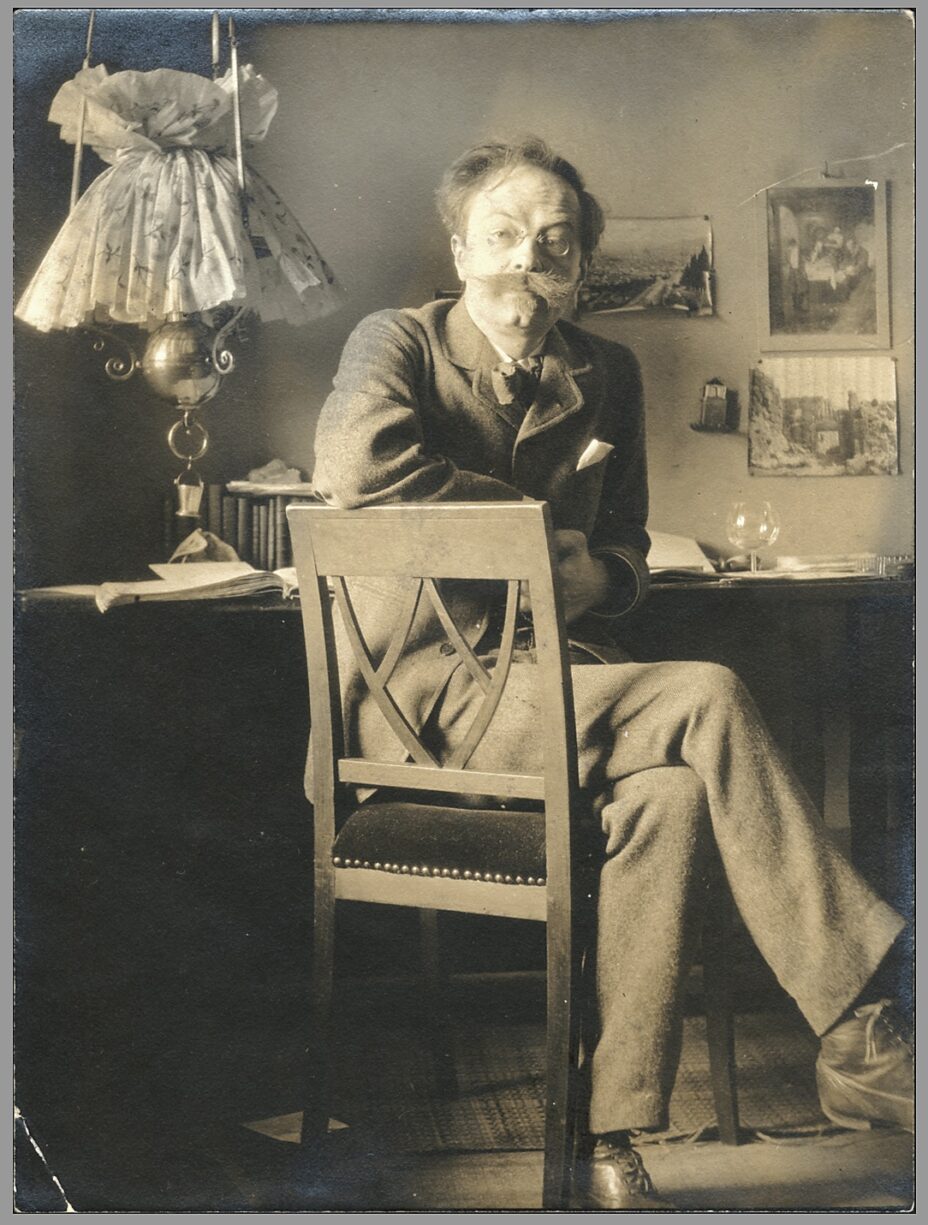

Although Diepenbrock, being mostly self-taught as a composer and a conductor, continued to teach Latin, Greek and philology until his death, he also guided several young musicians, as well as composers (among whom Matthijs Vermeulen, Willem Pijper and Hendrik Andriessen) and singers whom he accompanied at the piano. Being an accomplished author and critic, too, he commented on a wide variety of topics in journals and newspapers and was much admired by the members of the literary movement known in the Netherlands as the ‘Tachtigers’ (the generation of the Eighties, active from the early 1880s onwards, and much influenced by literary Naturalism and Symbolism, by French authors as Verlaine, Mallarmé and Baudelaire, and the theories of Wagner and Nietzsche).

However, by far the most important fact was for him the appointment of Willem Mengelberg as conductor of the Concertgebouw Orchestra. Within a few years Mengelberg became an ardent interpreter of his music as much as he was of the symphonies of Gustav Mahler. Diepenbrock met Mahler in autumn 1903, when the latter visited Amsterdam for the first time to present his Third Symphony. The two composers soon became friends. Since as early as 1900 Mengelberg had invited Diepenbrock to conduct his own music with the Concertgebouw Orchestra, both composers had much to discuss, about music, conducting, literature (both were avid readers of poetry and philosophy, especially Nietzsche). Mahler’s symphonies and especially his symphonic songs had a considerable influence on Diepenbrock. The reverse, though, was just as much the case: Diepenbrock’s symphonic songs were real orchestral pieces from the beginning, whereas before Das Lied von der Erde Mahler’s were orchestrated piano songs.

Another point of common interest between Diepenbrock and Mengelberg was their Roman-Catholic faith and their strong bond with the Catholic culture that had informed life in the Netherlands since the sixteenth century – though it was forbidden, hidden and denied any public existence. Only in the middle of the nineteenth century was a bishopric restored and an episcopal hierarchy in The Netherlands re-established. Since the Diepenbrock family was by family bonds strongly connected to such Catholic leaders as Joseph Alberdingk Thijm, the author Lodewijk van Deijssel (pen name of Karel Alberdingk Thijm) and the architect of many Roman-Catholic churches, Pierre Cuypers.

In line with the re-emergence, one of the most often performed of Diepenbrock’s works, his Te Deum laudamus for soloists, mixed chorus and orchestra (1897), premiered by Mengelberg and the Concertgebouw Orchestra on January 10, 1902, was a huge success, repeated by the Orchestra over thirty times within half a century. The quintessentially Diepenbrockian Missa in die festo (1890–94), composed for tenor, eight-part double male chorus and organ is a fruit of the revival of Catholic music in the Netherlands. This magnificent score contains a unique mixture of Palestrinian polyphony and Wagnerian chromaticism.

Diepenbrock was in his genes a vocal composer, for whom his faith and his believe in a specifically Roman-Catholic culture (opposite to the Prussian Protestantism that manifested itself since 1871 with the new ‘second’ German Empire) resulted into a predominantly vocal œuvre, religious and secular, always connected to either the language of the church, or to poetry and the theatre.

Diepenbrock’s theatre music occupies a category all its own. It was in this genre – following Marsyas, of De betooverde bron (‘Marsyas, or The Enchanted Spring’), that he was able to profess his love in the final ten years of his life for Vondel (Gijsbrecht van Aemstel), Goethe (Faust), Aristophanes (De vogels) and Sophocles (Electra). These works demonstrate the extent to which Diepenbrock explored and immersed himself in a world that was – in his view – still linked via a single, unbroken thread to the culture of antiquity.

This almost exclusive orientation towards language and text explains the complete lack of symphonies, concertos, string quartets or sonatas in Diepenbrock’s output. His first existent work is a song, Blauw, blauw bloemelijn (‘Little Blue Flower’), composed while he was still in high school, as was his unfinished last one, too, Roses dans la nuit, of which only eight bars have survived.

With my new book on the life, times and music of Alphons Diepenbrock, and with the many recordings available of his vocal and orchestral music, Diepenbrock’s music can finally be fully evaluated in the perspective of his time, between Palestrina, Wagner, Mahler and Debussy, and as pioneer and coach for younger generations after him.