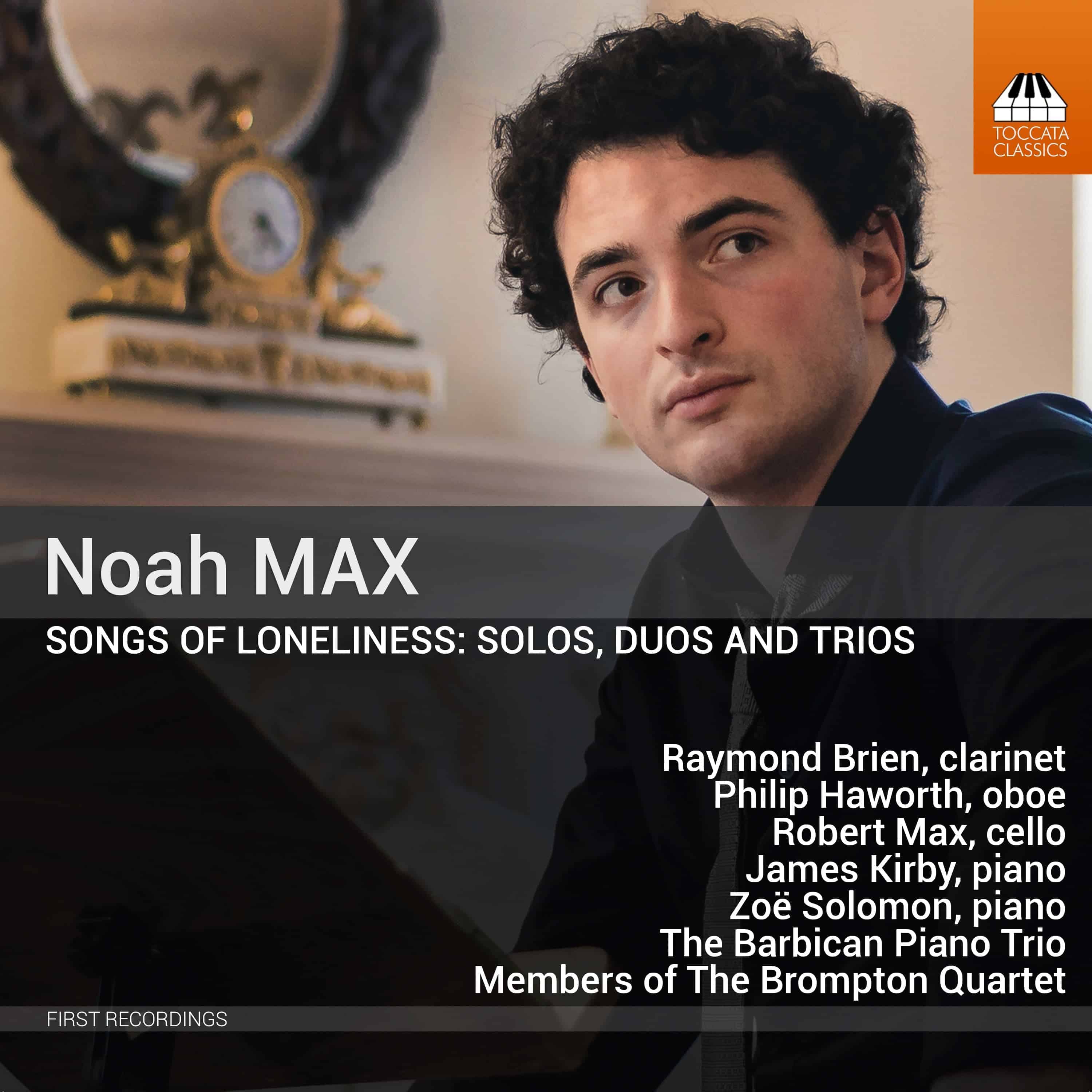

In March 2022 Toccata Classics released an album of music by Noah Max (b. 1998) – painter, poet and conductor as well as composer. Since then, Noah has been busy – well, he’s always busy – putting the finishing touches to a new chamber opera, A Child in Striped Pyjamas, John Boyne’s story of two children who become friends on either side of a barbed-wire fence – one the inmate in a concentration camp, the other the son of the camp commander. An article about it appeared in Classical Music last September, but there’s no point in clicking on the link for tickets for next week’s two performances in The Cockpit Theatre in north London – both have been sold out since early December. I recently took the opportunity to talk to Noah not so much about the music but about his own Jewish background and, indeed, the very idea of writing music ‘about’ the Holocaust. You can read and listen to our conversation below:

My maternal great grandparents, Chaim and Clara Tennenhaus, escaped from Vienna; they were Austrian. They were relatives of the Freuds, so there’s a family connection with Sigmund and Anna, and the painter as well, Lucian Freud. So all those things I find quite interesting because I think there’s a real ‒ you know, Vienna, prior to that time, was such an artistic hotbed, and it’s sort of a marriage of my artistic interests in, you know, not just in music but visual art and my intellectual interests, so having this great-grandfather who was a doctor of divinity ‒ and, you know, a real philosopher. My great grandparents escaped Vienna in 1938 and came to the UK, and my great-grandfather Chaim was interned on the Isle of Man for a period of time as an ‘enemy alien’ when Churchill said, famously ‒ or not famously, as the case may be ‒ ‘Collar the Lot!’

‘Collar the Lot’, that’s right.

That is all in the background. I’m aware of the fact that I’m here as a product of, one could say, of luck, the random chance that my great grandparents narrowly avoided the very terrible fate which befell so many Jews last century in Europe. That is something which I feel is, you know, is part of who I am, it’s a responsibility, I feel a necessity to live up to, and in doing this piece it has inspired me to insure I am taking the project with the requisite seriousness. When my great-grandfather came to the UK, he was actually originally a part of the Belsize Square Synagogue community, part of the original membership, he was quite involved as a very religious man and as a doctor of divinity, and, you know, that was a synagogue community founded by immigrants to the UK, you know, with that European tradition. But I have grown up going to West Hampstead Synagogue, which is on Dennington Park Road, with Rabbi Doctor Michael Harris, who is an author and a philosopher as well as a rabbi, and a very deep thinker and academic man, who I admire very, very deeply, and that’s had an impact on the texts I read, the way I think, and being part of that community and understanding actually what it means to be a modern Orthodox Jew in the 21st century had I think had a profound effect on my character, my sense of moral values, and that everything I do should in some way be geared towards that. Certainly, my interest in Biblical stories, in terms of the stories I’ve set to music, and I think this is the piece in which my love and knowledge of Jewish liturgical choral music, which I sang as a teenager, in the synagogue on High Holy days, has become most integrated with my language, and I think that’s something particular to me, because that repertoire is not often done in the concert hall, it’s very poorly known outside Jewish circles. There are great masterpieces among that repertoire.

People like Lewandowski, that kind of composer?

Precisely. Absolutely. And there is actually a Lewandowski manuscript rescued from Kristallnacht now, in the Belsize Square Synagogue, which I saw just the other day, and I’m working to bring composers like Lewandowski ‒ we actually did his Shuvi Nafshi in a concert with Epiphani Consort and Echo Ensemble in October, so I’d like to bring it into the concert-hall context. It’s a repertoire that shaped me, which didn’t shape my contemporary musicians and composers, so I’d like to integrate it with my musical language, and this opera is the biggest step I have taken so far towards doing that.

If you go back to pre-war Austria and Germany, there are a lot of Austro-German Jews who, when Hitler brought in these interdictions for Jews in public life, a lot of them thought: ‘We’re Jewish? Are we really?’ It hadn’t occurred to them to think of themselves as anything other than German or Austrian. Now, I remember a theme that was discussed in TheNew York Times maybe ten or fifteen years ago and the phrase that the author of that article used was that the identification of Judaism with the Holocaust meant that it was a paradoxical thing, of Jews being partly defined by a movement which was intended to wipe them out. And the author of this article described it as a ‘ghastly embrace’. How do you square that circle, as a Jew writing about a subject which you ought to find anathema?

It’s important that Jews don’t base their identity, at least solely, on the Holocaust. If you’re going to base your Jewish identity on the persecution of Jewish people, then, you know, the Holocaust obviously is huge in scale, but it’s by no means the beginning. The Jews were expelled from almost every country at one point or another. I think we were among the first, if not the first, to do it here in this country. In fact, none of my non-Jewish colleagues actually know about the Clifford’s Tower massacre [in York] in 1190, and the expulsion of the Jews in 1290, and the fact that British Jewry as we know it today is only 350 years old. So I had a conducting teacher at one point who was a member of a Reformed Jewish synagogue, and he tended not to really engage with his Judaism a great deal, didn’t really go to synagogue. And when the Pittsburgh massacre occurred, I had a lesson from him that morning, and obviously we talked about the disaster itself, and then he was reflecting on his own Judaism, and he said ‘It’s so sad, what it means to me to be Jewish is that I try my best to be like everyone else, and then something like this happens and I realise I’m not’. I think what was different about the Nazis in previous eras is that in mediaeval eras Jews were criticised for their religion and they were told that if you converted to Christianity you could be saved. Of course, at the Clifford’s Tower massacre, because they said: ‘If you come out and you agree to convert to Christianity, we won’t hurt you’, so some people came out and they massacred them anyway. So whether that’s truly the case, it’s kind of a grey area. By the time it got to the Nazis, it’s post-Enlightenment, what’s so disturbing about the Holocaust particularly is that it emerged from this post-Enlightenment mentality, where Enlightenment was, you know, rationality can answer every question: the key to the universe is within our grasp. It produced these great artists and thinkers like Goethe and Beethoven and Nietzsche, but it also, the Holocaust didn’t come out of anarchy and nihilism and chaos, it came out of this over-abundance of order, and this ‒ as David Baddiel, the comedian, often says ‒ the Nazis wouldn’t have asked whether I kept kosher, it was about my blood, it was a very strange, cult-like obsession with purity of blood, of German blood, and so you could be a third-generation immigrant ‒ you grew up in the country, your parents grew up in the country, you spoke the vernacular language, but because you had a grandparent or two who come from somewhere else, and you didn’t even really understand where, all of a sudden you were a target on their list, and so this whole debate, what is Judaism, and how do we engage with it, is it a race, is it a religion, is it a way of life, is it, you know, a story? And I think it’s all the things and more, and the process of writing this opera brought me closer to my religious practice and my faith than ever, and I am now a practising Jew again. I now go to synagogue again, which I didn’t when the process started five years ago. I’d lapsed, I’d stopped going, the core of my Jewish identity is a deep moral commitment to the idea that these ancient, sacred Old Testament texts are indeed that. They are sacred, and the reason why we treat them as such is because they contain timeless moral truths, which, if we adhere to them with care, make the world a better place. And I really do believe that.

The other question I wanted to raise is the objection that, even though it started life as a novel, rather than a bit of historical truth, is the objection that by setting something like that ‒ I mean, the same objection could be raised against Passazhirka of Weinberg, for example, by setting it to music, you falsify it, and you make it somehow less objectionable than it was. To which the response, of course, is yes, but you can give it that heightened emotional impact in music that, if you just watch a film about Auschwitz, it will lack, as when you make a recording of the piano, you’ve got to falsify the sound to make it sound more natural. You know, you’ve got to add reverb and you’ve got to compress it, because otherwise the pianissimos will be inaudible and the fortes will be so bloody loud you have to rush to the [controls]. You have to falsify it in some way to make it comprehensible.

Yes.

Even though you’re doing an injustice to the technical veracity of the subject matter, you’re actually giving it a kind of edge, which the sheer, the vulgarity of evil is the phrase that comes to mind,

Banality of evil, Hannah Arendt…

Yes. By setting it to music, you’re overcoming that objection about the banality of evil.

Is it appropriate to make art about the Holocaust? Is it ethical even to try? An old, wise friend of mine once said ‘Art is short; it’s an abbreviation of “artifice”’, and it does exactly what you’ve just said, which is it’s not demeaning, actually it elevates it. Opera is a very artificial genre in some sense, and I deliberately went for a story that wasn’t true, over trying to tell a true story on stage. You know, you couldn’t do If this is a Man in an opera. And I think there’s a reason operas about true stories don’t tend to work well, because the strength of opera is in the deep symbolic content. Whether or not it’s appropriate to make Holocaust art is a moot point, because I’m an artist; that’s what I do, I’m a composer, so things I have strong feelings about are going to come out through my compositions, and my job, as far as is possible, is to be as useful as possible in a moral sense to society. On a philosophical level, I think it’s difficult because obviously these great works by Primo Levi, Viktor Frankl, Edith Eger, Elie Wiesel and all the survivors, they are crucial reading, for everyone. Are they literature, or are they documentaries? And, you know, some of them straddle the boundary between art and life, and so, you know, Primo Levi, If this is a man is undoubtedly a documentary, but then he wrote a novel, If Not Now, When?, which is a composite of real events that did happen into a story which didn’t. So I think Viktor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning is a very deep psychological text, and I think there’s absolutely something true about it, the existential nature of what he’s writing about is incredibly pertinent. Elie Wiesel asks incredibly important questions about, you know, where was God in the Holocaust. He writes about his faith, and about how he ends up becoming angry with God, and it’s not clear where he stands on whether he truly believed by the end of it that God existed. It was Elie Wiesel who said, you know, there can be no art about after the Holocaust. And with greatest respect, I actually disagree. And I can see why, having been so close to the issue himself, having been there, I would be difficult to understand why somebody removed in space and time from himself would find it valuable to go to an opera of a fictional story about the Holocaust, but I think both need to be able to coexist. I hear too much enmity between artists and Holocaust educators criticising one another for the gaps in their methods, and I think, practically speaking, both are correct. We need both. We need robust Holocaust education on the facts, and we need deep artistic engagement with the ethical and spiritual matters that are at hand.