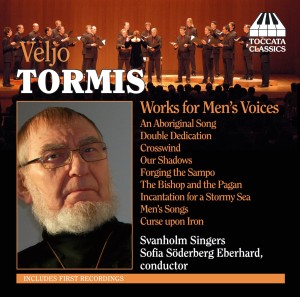

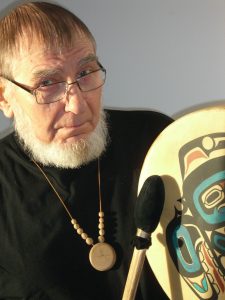

I am much saddened by the news of the death of Veljo Tormis on Saturday, 21 January. Tormis was as significant a figure in the forging of Estonia’s cultural identity as Sibelius was in Finland’s. His music is instantly identifiable and physically engaging: it has an energising power – and there is an astonishing amount of it: he was a very busy man. He also had a wonderfully warm personality, modest in manner but deeply engaging, and I was proud to call him a friend. I published an interview with him in Tempo (New Series, No. 211, January 2000, pp. 24–27), and reproduce it here, more or less as it appeared then, footnotes and all, rather than attempt to update it. I had no idea at the time that I would be launching Toccata Classics a few years later, much less that Veljo would feature on the label as a recording artist, but he plays the shaman drum on the Svanholm Singers’ recording of his Raua needmine (‘A Curse upon Iron’), his best-known work, on TOCC0073. I salute his memory.

Veljo Tormis, who will be 70 on 7 August 2000, has become – de facto rather than through any external sign of age – the Grand Old Man of Estonian music1. Although he will celebrate the event in an Estonia enjoying its tenth year of liberty, for the three preceding decades, though most of the dark night of Russian occupation, Tormis’ music, based on regilaul, the primitive runic folksong of the Estonian people, was an important repository of ethnic identity.

Tormis was born at Kuusalu, some 30 miles due east of Tallinn. He first studied organ in August Topman’s class in the Tallinn Conservatory in 1942–44, graduating from the Tallinn Music School as an organist (under Salme Krull) in 1947. Still at the Tallinn Music School he then studied as a choral conductor under Jüri Variste, before taking composition lessons from Villem Kapp in 1950–512. After his composition studies with Kapp, Tormis moved to Moscow, where he studied with Shostakovich’s friend Vissarion Shebalin (1902–63), graduating in 1956. From 1955 to 1960 Tormis himself taught music theory and composition in Tallinn Music School and has been active as a freelance composer since 1969.

His output is vast, its backbone formed by some 250 choral pieces, some of them free-standing songs but others cycles of considerable scope. Like many composers in the former Soviet Union Tormis turned his hand to film music, writing some three dozen scores; and there is also a handful of orchestral and instrumental works in his catalogue, early works all of them,3 since when he has composed almost exclusively for chorus.

In the Estonia Concert Hall in Tallinn I asked Tormis, an affable and easy-going man with a ready laugh, when his involvement with choral music began.

Since childhood I have been living in choral music: my father was a choir conductor and organist in a little village.

And was folk music, too, a prominent part of his childhood?

It was mostly church music, not folk music, and it was not connected directly with folk music. I had my first connections with folk music through Estonian composers, not directly: Mart Saar4, Cyrillus Kreek5, etc., etc.

Did he begin his own researches from that point onwards?

It was as a student in the Conservatoire that I became acquainted with folk music. Edgar Arro6 sent me to the countryside, museums, and so on; we have very rich archives.7

So it was a joy in the ethnomusicology discoveries he made there that sparked an ambition to compose?

No, first I wanted to be an organist and then later a choir-master. But then in ’48 the organ class was closed on ideological grounds; it was Stalin. Then I had to choose another profession! What could I do in my situation? Then I tried choral conducting, but that didn’t work: there weren’t any churches. Then my choir professor said: ‘It’s not for you – choose another profession”. So composition was the third possibility!’

Harry Olt’s invaluable guide Estonian Music offers a useful thumbnail guide to the constituent elements of Tormis’ style: ‘Imitation, parallel chords in gradual, step by step motion, rhythmic variations with respect to the rhythm of the text, and monotonous repetitions around certain motifs’.8 How did the runo-song primitivism that makes Tormis’ music so distinctive evolve?

I didn’t just discover it one day; I was a long way on the approach to it. It was ten years after I was at the Moscow Conservatory, after I had written orchestral pieces and an opera9, that I discovered the real value of this regilaul. Then I tried to bring the structure of regilaul into my own compositions. My first big work was Estonian Calendar Songs.10

Tormis’ studies of the folksong tradition on which he has drawn ever since drew him to the conclusion that

old Estonian folk songs are an intact part of an ancient culture where all the components are combined in structure: the melody, the words, the performance, etc. It also became clear that it is a very old pre-Christian culture which is shamanistic in substance, and extremely close to nature in the ecological sense.11

But his attraction to Estonia’s distant past is no mere nostalgia:

Self-apprehension and self-cognition is vital for maintaining balance and viability. We should know who we are and where our roots lie. Then it is easier to set up goals for the future.12

One obvious characteristic of Tormis’ music, apart from the rhythmic punch of its relentless ostinati, is its harmonic astringency. As a result, it looks deceptively bald on the page: the sense of growing excitement that immediately hits the ear isn’t always obvious to the score-reading eye.

I often build works over a pedal point. Our solo songs don’t lend themselves to harmonisation, as it used to be done in Romantic music. Our classical composers also use these melodies – very short, in three, four stages. You can’t harmonise them, so I was looking for other possibilities: parallel chords, clusters.…

For Estonia under the Soviet yolk, as for the other two Baltic countries, Latvia and Lithuania, song was a vital expression of national identity. The Soviet authorities tolerated, and tamed, the Üldlaulupidu, or United Song Festivals, that have been held in Tallinn every five years since 1869, attracting some third of the entire population of Estonia as performers (30,000) or listeners (300,000).13 One imagines that Tormis’ explicitly nationalist compositions must have generated political difficulties for him.

Yes, during the days of Stalin, of course, and they were forbidden in the ’60s and ’70s, these works. It’s complicated, and paradoxical. In 1948, when they were shouting about formalism, they said, ‘Please look for folksongs’ – but it was a very good slogan for me! In the ’60s and ’70s the Ministry of Culture here said, ah, that’s nationalism. It took them thirty years to understand what I was doing! I was not a fighter, not a dissident14 – but our public understood what I wanted to say in my national, folk-based work.

The ability to communicate through art is a constant in discussions with musicians who lived through the Soviet oppression. The best-known practitioner of such virtuous double-speak is Shostakovich, of course; and the Czech composer and organist Petr Eben told me in interview how he used music to reach to his audience past the censors:15

art could sometimes say things that otherwise couldn’t be told. For the same reasons that things didn’t get into the newspapers, people would like to go to the small theatres rather than the National Theatre because there things were said that couldn’t be pronounced elsewhere. People became accustomed to reading between the lines. In literature and painting it was quite difficult because the censors understood if there was something against the government. But music was abstract and it was not so easy to survey. So if I quoted a Gregorian motif, the people from the churches would know it and enjoy it; they would know that this was a spiritual work – but the Union of Composers would have no idea! In this way composing for me was a sort of message for the people.

Tormis laughs at the bitter-sweet memories this account invokes:

We had a joke here that you must sing in Latin. Some songs you had to sing in Latin, in order that our Communists would not understand: they knew only Russian. Some songs were translated into Latin to protect the songs, though their original language was Estonian. Now, of course, it’s good because you can sing it all over the world and everybody knows the Latin language. All the Kalevala, the Finnish national epic, is translated into Latin – it was special done as a present for the Pope in Rome. A pagan epic in Latin – that’s something! Latin is a very good language to translate the Kalevala and Kalevipoeg.16 The old Greek and Latin epics are in quantitative verse, and we have quantitative verse in regilaul as well.

This talk of epics raises another question: now that Tormis is free from political constraints to compose whatever he wants, does he have plans for any lager-scale works? Wagner, after all, contemplated crowning his career with a symphony, and Bruckner was toying with the idea of an opera.

These forms are not for me. I have written a big stage work: that was Estonian Ballads, a cantata-ballet.17 The libretto was written by my wife [Lea]. Everything in it is from folksongs.

One of Tormis’ biggest works is Forgotten Peoples, a cycle of six further cycles based on songs by ethnic groups who, as the title suggests, were already dying out or were dead as living cultures when in 1970 Tormis began the twenty-year task of its composition: the Livonians from the Gulf of Livonia (renamed the Gulf of Riga by the Communists, long after the Livonians had been subsumed by Latvian culture); Votians, Izhorians and Ingermanland Finns (Igrians) from the coastal areas between Tallinn and Leningrad; the Vepses, east of Lake Ladoga; and the Karelians in the part of Finland north of Leningrad that was captured by the Soviet Union during the Second World War, though there were pockets of Karelians as far south as Tver18. Is Tormis’ music now all that is left of these ancient peoples?

The Vepses are still alive, and so are the Karelians. But the Livonians, Votians…

His voice trails away, and then revives as he recalls contemporary moves to preserve this heritage before it slips away entirely:

But there is in Latvia a folk ensemble that is half-Latvian, half-Livonian. And we have these Finno-Ugric days here, when all the Finno-Ugric peoples come, and they sing the same melodies as I have used in the first piece in Livonian Heritage:

Tšitšor-linkist, tšitšor-linkist,

ni um aaiga ilzô nuuzô,

tšitšor, tšitšor’.19

This common heritage of Finnish and Estonian folk literature has allowed Tormis also to treat material that may be more familiar from Finnish sources: ‘Undarmoi and Kalevoi’, for example, the tenth song in Tormis’ Izhorian Epic, relates the same tale of slaughter and revenge as Aulis Sallinen’s opera Kullervo (1986–88), though in in two-and-a-half hours’ less time. Tormis laughs.

That may be, yes. For example, I’ve written for the Hilliard Ensemble a piece called [in English] Kullervo’s Message20 and a piece for the King’s Singers on Finnish historical material.

Tormis’ mention of these two British vocal groups suggests that, now as his fame spreads and his music is at last becoming familiar to audiences outside the Baltic republics, he must be getting commissions from far further afield.

Yes, but I have very little energy.

He taps his chest: he had a heart attack six years ago. So he is taking things easy?

We are living in a house in the country, outside Tallinn. Tallinn is a very difficult town, psychologically.

Didn’t the lifting of the Soviet yoke nonetheless bring a surge of adrenalin to music-making in Estonia?

The first period was very difficult. We had lost all our western public and had very little contact with the west. But they have come now: Warner and Fazer Edition, ECM too. We had before a window through Finland – and our window to Europe was Finnish TV!

Fazer Edition, indeed, has become Tormis’ main publisher and they are slowly catching up with his enormous output. For Tormis himself it is a mixed blessing:

I am busy correcting proofs for Fazer, all the time. I am working as an editor!21

I am obliged to Sirje Normet for help with translation during this interview.

- Strictly speaking, that title should belong to Heimar Ilves, whose 85th birthday fell on 15 September 1999. But though his reputation as a highly respected teacher and powerful composer endures, Ilves these days is as much a private figure as Tormis is a public one.

- Kapp (1913–64, nephew of Artur Kapp) likewise studied organ with Topman, in 1938, and in 1944 took composition lessons from Heino Eller (1882–1970), who taught virtually all the important Estonian composers of the next three generations, his youngest students now active including Arvo Pärt and Lepo Sumera. Villem Kapp’s own compositions, somewhat Romantic in style and incorporating elements from Estonian folk music, include two symphonies, a wind quintet, an opera (Lembitu) and a cantata, Kevadele (‘To Spring’), as well as other chamber works, piano music and some 50 choral songs.

- Tormis’ Overture No. 1 dates from 1956 and the Overture No. 2 from 1959; earlier still (1952–53) is a three-movement Violin Sonata, and Three Preludes and Fugues for piano were composed in 1958.

- Saar (1882–1962) is one of the father-figures of modern Estonian music. Like Rudolf Tobias (1873–1918), the true founder of the Estonian tradition of classical music, Saar studied in St Petersburg with Louis Homilius (organ) and Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov (composition). He was one of the first to begin the systematic collection of Estonian folksongs, and many of his own compositions, like Tormis’, draw on folksong for their inspiration and material. A number of Saar’s early orchestral works were destroyed in a fire in 1921; some piano and organ pieces apart, almost all of his surviving music is for voice, in the form of solo and choral songs and suites.

- Kreek (1889–1962) is another of the founders of modern Estonian music, again studying at St Petersburg, his composition teachers being Vasili Kalafati, Joseph Vitols, ….. Tchernov and Nikolai Tcherepnin. Kreek, too, wrote a generous quantity of a cappella choral music (including 150 choral songs and 1,300 folk-chorales) and was active as a choral conductor. He also composed a number of works for orchestra and chorus and orchestra, the best-known being the Estonian Requiem of 1927.

- Edgar Arro (1911–78) studied at the Tallinn Conservatory with August Topman (organ) and Artur Kapp (composition) and taught there himself from 1972. From 1952 to 1966 he was secretary of the Estonian Union of Composers. His own compositions include a number of works for organ, some 130 choral songs and (together with Leo Normet) the operetta Rummu Jüri, which ran for over 200 performances at the Vanemuine Theatre in Tartu.

- Tormis is not exaggerating: by 1914 the Estonian Student Union (Kreek, Saar, Peeter Süda, Juhan Aavik and others) had collected no fewer than 13,226 folk tunes, and the archives in Tartu now hold over 30,000 folk melodies – probably one of the biggest collections in the world.

- Perioodika, Tallinn, 1980, pp. 148–49.

- Luigelend (The Flight of the Swan), 1965.

- Eesti kalendrilaulud, composed in 1966–67, comprises five smaller cycles containing a total of 29 songs: Martinmas Songs (male chorus), St Catherine’s Day Songs (female chorus), Shrovetide Songs (male chorus), Swing Songs (female chorus) and St John’s Day Songs for Midsummer’s Eve (mixed chorus). The Calendar Songs have been recorded, together with Three Estonian Game Songs, by Tõnu Kaljuste and the Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir on Virgin Classics 7243 5 45185 2 2. In his notes to this recording Tormis states proudly that ‘Estonians have lived within the boundaries of their present habitat for about five thousand years (a European record?)’.

- Quoted in Tiia Järg’s notes to the Forte CD Epic Fields (fd0030/2), a Tormis anthology recorded by the Estonian Radio Mixed Chorus conducted by Tõnu Kangron and Ants Üleoja, released in 1995.

- Quoted in Vaike Sarv’s notes to the Finlandia CD People of Kalevala (0630-12245-2) a 1996 Tormis anthology sung by the R. A. M. Choir (National Male Choir of Estonia); no conductor indicated. In a second Tormis collection released by Finlandia in 1996 – Bridge of Song (4509-96937-2) – the Estonian Radio Choir is conducted by Toomas Kapten.

- Having attended the Latvian Song Festival in Riga in July 1998, I can vouch for the effectiveness of these occasions in inculcating a dignified sense of national identity: the sound of hundreds of thousands of voices all around you picking up a national hymn does more than stir the hair at the base of your neck – it touches something very basic in the human make-up. A Forte CD (fd0009-2), recorded in part live at a number of Estonian song festivals, communicates something of the electric atmosphere of these events.

- Tormis nonetheless often sailed close to the political wind in his choice of the texts he set, the meaning of which must occasionally have been hard to overlook. In (for example) Maarjamaa Balaad (Ballad of Mary’s Land), composed in 1969, the inference of Jaan Kaplinski’s text, ostensibly about events in the thirteenth-century, must have been fairly obvious: ‘hammers are hewing stones on the hill, a foreign language is heard’.

- Fanfare, Vol. 19, No. 6, July/August 1996, p. 49.

- The Kalevipoeg is the Estonian national epic, closely related to the Finnish Kalevala; and as the Kalevala was collected and fashioned by Elias Lönnrot, so, too, the Kalevipoeg was compounded from folk material collected in field trips by Friedrich Reinhold Kreutzwald (1803–82). Cf. the website maintained by the Institute of Baltic Studies and Helen McEwan, ‘The Writing of Kalevipoeg as the Estonian National Epic’, Slovo, Vol. 11, 1999, pp. 00–00. Tormis has used the Kalevipoeg in several works, the biggest of them being the ‘Epic Cantata’ Kalevipoeg, for tenor, baritone, mixed chorus and orchestra (1954–56) and Vanemiune, a cantata for mixed chorus and orchestra (1967).

- Composed in 1979–80

- Forgotten Peoples comprises Livonian Heritage (1970), Votic Wedding Songs (1971), Izhorian Epic (1975), Ingrian Evenings (1979), Vepsian Paths (1983) and Karelian Destiny (1989). All six cycles were recorded in 1992 by Tõnu Kaljuste and the Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir on a ECM New Series double-album (434 275-2) – the first recording of Tormis’ music to be issued in the West. ECM has just released a new Tormis anthology performed by the same forces: Litany to Thunder (465 223-2).

- Tšitšor-birds, tšitšor-birds,

Now it’s time to wake,

tšitšor, tšitšor!

The opening lines of ‘Waking the Birds’, the first song in Tormis’ cycle Livonian Heritage. - Recorded by them in A Hilliard Songbook: New Music for Voices (ECM New Series 453 259-2); The Hilliard Ensemble has also recorded Tormis’ Estonian Lullaby on the ECM New Series album Mnemosyne (465 122-2).

- Tormis’s modesty is such that, when I spoke to him in November 1999, he didn’t at first mention the forthcoming premiere, within a month, of Sünnisõnad (‘The Birthright’), for mezzo soprano and tenor soloists, three choirs and orchestra, a 35–40 minute cantata written earlier in the year.