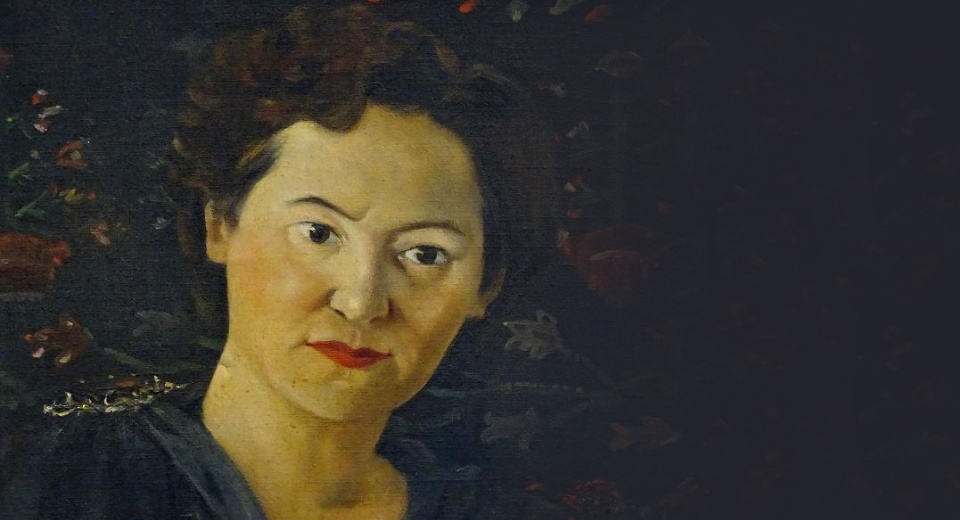

The composer David Hackbridge Johnson reacts with surprise to the piano music of the unknown Freda Swain (1902–85) – whose music, after her death, spent some time stacked in boxes in a friend’s garage.

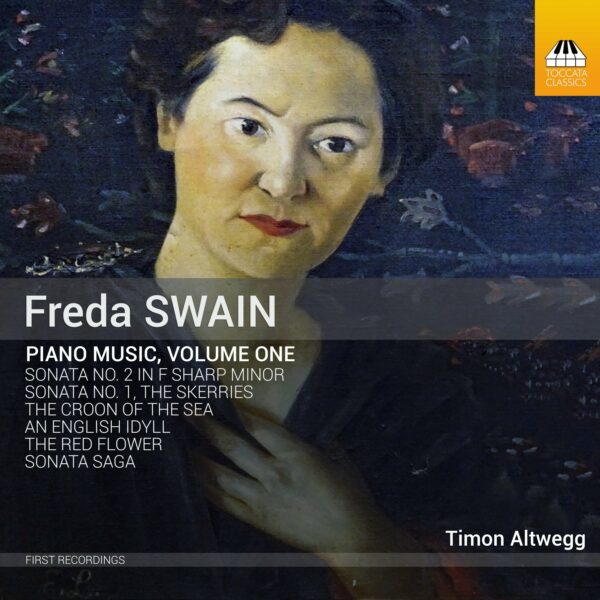

Freda Swain is one of those names I half-remember from my early years as a rather reluctant piano student. Did her name appear as the composer of piano miniatures in examination pieces for The Associated Board of the Royal Schools of Music? Always in list C with another F. S. – Felix Swinstead? Was she still at The Royal College of Music when I auditioned for a place in 1981 – her name on a brass plate outside a practice room? Did some melodic shapes and harmonies creep into my unwieldy hands and remain there waiting for ears to latch on to them in later years? Is that why there is an eerie ring of familiarity in the music of Timon Altwegg’s album of her piano music? Whatever lurking memories I possessed are brought into a startling present with his Toccata Classics release (TOCC 0579), which should establish Swain as an important and so far unsung composer of piano works worthy to stand alongside her better-known contemporaries.

What best sums up her music? A largely Romantic approach, with rich textures and a sweeping command of the piano as an instrument of unique possibilities of sonority – this approach tempered with clarity of ideas and execution. A sense of unnamed dramas unfolding over landscapes that switch from dark foreboding to glittering colours. A pianist and a composer combined, with all that that implies in terms of far more illustrious twentieth-century musicians who cover both disciplines. Nearly 40 years after her death, Freda Swain’s music is now to be heard once more, thanks to the advocacy of Timon Altwegg – her manuscripts, packed into many boxes, came to him some years ago, and this album is the fruit of his years of cataloguing, deciphering and typesetting, all in preparation for live performances and those in this recording.

The Sonata Saga in F minor begins in the darkest of moods – a searching unison line that winds in on itself as if questing for the light. The harmony when it opens out is full of fifths, both perfect and diminished. Rhythmic gestures are redolent of Bax and Ireland – indicative of the ballad form in which they both excelled, that is, a form and approach to the piano that is essentially freely expressive and where musical material is at once hierarchical and yet subject to the most extreme forms of distortion, as in the model provided by Liszt. A rich chromaticism establishes the roles for inner voices and is again Baxian. But can a leaner classical bent be discerned that suggests an affinity with Medtner? I think that might be so in the development section of the first movement, where major triads jostle among more contrapuntal elements in the manner of the Medtner’s ‘Knight Errant’, the second of the Two Pieces, Op. 58, for two pianos (1940–45). It is safe to assume Swain knew both Medtner and his music, since her husband, the New Zealand-born, British-domiciled pianist Arthur Alexander was a close friend of Medtner and an early interpreter of his music – surely Arthur and Freda played Medtner’s two-piano works (‘Russian Round Dance’ in addition to ‘Knight Errant’) together. A fondness for organum-like manifestations – a texture than re-occurs throughout Swain’s œuvre – recalls Debussy, and yet these manifestations are not really present for impressionistic effect – any more than they were for Debussy – but rather to create a sound edifice, massive, looming and, if not entirely unmoving, at least reluctant to move. Towards the end of the movement Swain latches onto a series of parallel sevenths which are strikingly original in effect – indeed, this passage and the dissonant block-chords that follow it might remind some listeners of Sorabji. The oppressive coda condemns the listener to the depths – melodic shapes keening over the tolling of bells.

A motif – like a short fanfare, is retained in the slow movement which emerges as if from the overtones of the bells in the preceding movement. The motif proves capable of riding over an undulating bed of organum left-hand chords, with a rather tortuous harmonic trajectory, as if the music were in a permanent state of becoming. The triadic aspect is able to offer a glimmer of hope in this wracked landscape. The climax is not an easy resolution of these hopes into a glorious release but is rather a pinnacle of anxiety – the summit of a mountain, perhaps, from which only ruins below can be discerned. This movement alone in its relentless pacing, its unbroken momentum – like an electrical current running through – might rank it in the same column as the finer of Bax’s sonata movements.

In the finale, triads battle against a writhing left hand – granitic chords give a sure sense of the minor mode – at last relatively unadorned with chromatic gilding. A state of continual development characterises the propelling forces of the music – it is unrelenting in power and declamatory energy. The ending: epic, terrifying even, with the fanfare motif slamming into F major almost in desperation for escape.

It isn’t known what saga Swain had in mind (if any) when writing this sonata, but it evidently has a connection to the sea. As Timon Altwegg points out in his extensive booklet notes, the manuscript has a dedication to her husband on the title page together with a poem by Swain that begins, ‘To the sea and its vastness / its depth and remoteness’. One can hear how these lines are set (wordlessly) in the sonata: the sense of a huge volume of water bleak in aspect, pitiless in destructive potential; the way the piano seems to evoke waves, fluidic behaviour, is even inundated by its own peaks of sounds piled up upon one another like toppling liquid mountains. This sonata is worthy to join that esteemed cluster of piano pieces evoking water which includes Debussy’s L’isle Joyeuse, inspired by Watteau’s painting L’Embarquement de Cythère, Liszt’s Les Jeux d’Eaux á la Ville d’Este and Ravel’s Jeux d’eau – which incidentally also contains poetry on its published title page, Henri de Régnier’s line, ‘Dieu fluvial riant de l’eau qui le chatouille’ (‘River god laughing at water tickling him’). Though admitted to this illustrious company, Swain does so without sounding like any of the other composers in it: her sea does not tickle, nor is it joyous; rather, it surges and rolls, uttering, in Melville’s words, a ‘Wild song, wild light, in still ocean’s dark’.

Fittingly, Timon Altwegg continues his programme with a piece that reveals a body of water less stormy: the hauntingly beautiful The Croon of the Sea. Swain wrote it at the age of eighteen, when she was studying with Arthur Alexander at the RCM. A theme with a triplet incipits that will at once recall Delius is laid over a series of rocking pedal notes that anchor – yes, anchor – the music to a rhythm peacefully oceanic. The fluid middle section brings John Ireland to mind, both in harmony and in the way the music is laid out for the instrument – think ‘Song of the Springtides’ from his Sarnia: An Island Sequence. A rich palette of colours leads back to the opening – familiar but somehow made weighty, mournful even, by the darker ‘affect’ of the middle section. In a fitting coda, lights glimmer on the horizon in the form of precisely spaced major triads.

In contrast to Swain’s first work in the genre (which is unnumbered), her Piano Sonata No. 1 in A minor, The Skerries, is compact, innovative and succinct. Gone are the sea-monster depths and towering waves – but it is another sea piece, and so one can expect flow, and that is what Swain provides. Generally speaking, the texture is more lucid, with the hands often locked in the middle of the piano rather than spread apart to generate the mass-effects heard in the Sonata Saga. Counterpoint – often in only two parts – shows her to have mastered the challenge of keeping all voices both active and individually cogent – as is true of her bass lines, always a sign of the best composers. Harmonies are once more built from fourths and fifths; dissonance is not avoided and can reach a Tippett-like degree of piquancy. Cross-hand techniques abound in the finale which could be said to show a concerto-like layout in the piano writing; Swain did write a concerto – the ‘Airmail concerto’, so called, since she sent its sheets in instalments to her husband, who was abroad during its composition – and I’d love to hear this work by way of comparison with her solo-piano works… in addition to the obvious reason that it should be heard. The skerries-inspired sonata (a skerry is a small rocky islet) resulted from a trip to Scotland that Swain and Alexander made; I don’t know if she used any Scottish folk material but it might feel to some listeners – this one certainly – that folk music lies just behind the notes. There is a faint but detectable hint of the novel way Erik Chisholm approached his Scottish-themed pieces, or those of a composer born a generation after Swain and Chisholm, Ronald Stevenson.

Freda Swain’s An English Idyll is of that sort of striding-out music made so memorable by Percy Grainger – for example, his setting of ‘The Brisk Young Sailor’ from Lincolnshire Posy. The piece has a pleasing gait in spite of its G minor tonality. Via exquisite part-writing, the journey is made full of harmonic incident, seeming to want to fall into melancholy only in the middle section, where there are a number of halting cadences that momentarily impede progress. In all this apparent meander, there is a wonderful sense of how melody and harmony interact in perfect tandem – like walkers who know where they are going and get there in good time. I wonder if Medtner knew Swain’s music – this piece has many of the fine qualities to found in his Skazki. An exquisite piece, then, and yet more proof of what Ronald Stevenson once said to me in praise of Edvard Grieg – that it takes as much skill to write a miniature as it does a symphony.

With her Piano Sonata No. 2 in F sharp minor, Swain has built on the techniques of No. 1 to create a fascinating work vibrant with energy, daring in the context of British music at the time, and entirely successful in its attainment from a formal point of view. The leanness of the First Sonata is retained, and the harmony continues to evolve with much dissonance embraced within a largely tonal concept – one can now hear seconds and sevenths commonly used. Even the singing periods, as they might be called, are surprising in the way harmonic sleights of hand never allow the music to indulge in nostalgic reverie. In short, this is largely combative, spicy, vital music. The first movement is a toccata and apart from a few justifiable breathers is relentless, its shapes volatile, its harmonies kaleidoscopic. The key centre of F sharp minor is a useful marker only, as the formal scheme is so free-flowing as to inhibit immediate classical analysis – and yet the music is always on a leash, as it were: there is never a lull in that imperative keeping of the technical aspect in view. The second movement is a ‘Canzona Pastorale’ with a distinctly folk-like feel – an aching melody set over chords that are not so much a bed of leaves but a variegated patch of shrubs: expect thorns. A limpid quality allows for a more flowing middle section as an improvisational aspect of the initial material – as if a folksong were half-recalled and then put aside for the beauty of colours it inspires. Such freely conceived music is of a satisfaction that marks Swain as naturally gifted in the pacing and placing of each and every note she writes – witness the way the music falls away towards the end in a series of mysterious chords, over which the last wisp of melody says ‘farewell’. A short interlude – suggesting a poet reciting an introductory verse – precedes the last movement, called ‘Pandean Rondo’. Two-part writing – a long way from the shark-infested waters of the Sonata Saga – propels the music in a delight of its own making. Swain attains a coolness of delivery that reveals how multi-faceted is her Muse: the ending is throwaway, nonchalant, a joy. This is Pan at his most companionable, fluting away an afternoon in a pleasant grove with attendant nymphs. This third sonata is a fine piece worthy of far more than a foothold in the repertoire – which, of course, it has yet to gain.

Timon Altwegg’s album ends with another miniature, The Red Flower. It would attract any musician familiar with similar pieces by Ireland, Bax, even the forgotten Felix Swinstead. The Red Flower, despite its largely amiable nature, is nevertheless of some difficulty – I don’t think it ever appeared in an exam syllabus, at least in the lower grades; my clumsy mitts would have certainly baulked at it had it done so. The rather Baxian theme – like many of his, it has a hinge note around which the shapes revolve – is put through its paces by means of lively interactions and transmutations: the whole is a monothematic fantasia in effect. And effortlessly Swain shows how utterly at home she is in the medium – not complacently sitting in a moribund style (she never sounds ‘old-hat’) but letting her pianistic voice speak and evolve under her hands.

Pianists should not hesitate in exploring Freda Swain’s music – Timon Altwegg’s captivating performances must surely lead others to her rich and rewarding output. A vast archive of her work exists – boxes and boxes and boxes – and contains compositions in all forms; if the piano music recorded here is anything to go by, it will contain music of the highest standard. A voice almost lost, silenced even, boxed up for safe-keeping, waiting for a suitable time when it might speak. That time is now.