THE FINNISH COMPOSER TALKS TO MARTIN ANDERSON

In the light of the death of the Finnish composer Einojuhani Rautavaara, on 27 July 2016, in a Helsinki hospital, at the age of 87, I am pleased to post this interview he gave me in 1996. The warmth of his personality shines through his words as clearly as it does in his music.

MA, 28 July 2016

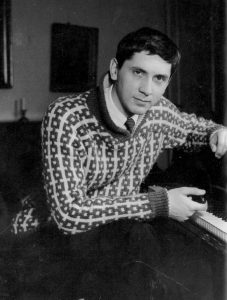

Ten minutes’ drive out from the center of Helsinki, down a lane lined with fir trees and piled high with snow, I climb out of the taxi, open a gate, wind my way round a tall and elegant house and ring the doorbell of the composer Einojuhani Rautavaara. Rautavaara, in his late sixties, soft-spoken, a tall, slightly gangling man with large, smiling eyes, ushers me in, helps me emerge from anorak and boots, puts me at my ease, sits me down with a coffee he has prepared in advance. I bring greetings from the baritone Jorma Hynninen, whom I had interviewed earlier in the day—and who had added an after-thought: “Tell him we are waiting”. This is because Rautavaara has been engaged for some time now on an opera on the life of the nineteenth-century Finnish Romantic writer Aleksis Kiivi. Rautavaara grins. “Well, I am now in the epilog of the opera, and I do want to send him a couple of the important arias to get his reaction before I write the final score.”

But I am here (I thought) not to talk to Rautavaara the opera composer but to Rautavaara the symphonist, thanks to the release of his Seventh Symphony, Angel of Light (ODE-899-2, coupled with Annunciations, for organ, brass and symphonic winds; Leif Segerstam conducts the Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra), on the Ondine label, now the major Finnish independent (and that after only ten years of existence). At least, that was my aim. I soon discover that Rautavaara’s art, and his life, are not so clearly divisible: his conversation spins through cosmic arcs, though his past, through his work; just when you think he has moved off a subject, the topic comes swinging back again, to make a unified whole—his talk is composed of symphonic paragraphs.

Rautavaara’s career as a composer of symphonies is charted in a major study by Kalevi Aho (himself proving to be a formidable symphonist, with his No. 9 now released on BIS-CD-706—and No. 10 in gestation), Einojuhani Rautavaara as Symphonist, published (in English, Finnish and German) by Edition Pan in Helsinki in 1988. Rautavaara’s first efforts in the form encompass a bewildering variety of styles: Aho describes the First Symphony as post-Sibelian, the modernist Second as showing “expressive formalism,” the Third as late-Romantic, the Fourth as “the first totally serial Finnish work” and the Fifth (after which Aho, writing almost a decade ago, ran out of symphonies) as “a synthesis of the romanticism and tonal aspirations of the Third Symphony and the modernism of the Fourth.” Rautavaara doesn’t contest these thumb-nail characterizations at all. ‘“I quite agree with him. He is my former student, so he knows quite well what I think and what I have done, and we are good friends. He quotes me from some time in the seventies as saying that I was almost horrified at the stylistic jumps between one symphony and another; and his explanation for it, a sort of Hegelian dialectic, is a very good one and very true. But one should add that until the Fifth Symphony—indeed, still—I considered myself a student, more or less, trying to learn what there has been, what there is in western music. I also consider all those thousand years of western music as a totality which should be the domain of the composer of today. I never understood the fanaticism of those modernists of the fifties and sixties who said: ‘Now we should never look backwards, we should never be anchored to tradition.’ For me tradition has been extremely important, and I am happy if I can be considered to be a part of the tradition. That I should only use the techniques of today, those invented after 1940—I think that’s senseless, that’s idiotic nowadays. I am talking against this quite a lot these days because that was the idea at Darmstadt when I was there too. But we are talking about the flogging of dead horses—I had to get these things clear for myself!”

So the stylistic jump from, say, the frankly Brucknerian Third Symphony to the strictly serial Fourth, Arabescata (recorded, with No. 5 and the Cantus Arcticus, on ODE 747-2), was part of a discovery process, a kind of exploration? “It is. My starting point was exceptional in that I studied music very late: I was seventeen when I began to study music and piano. When I came to the Sibelius Academy and said ‘I want to be a composer, that’s why I am here’, and I had colleagues there like Joonas Kokkonen who was a good pianist and Einar Englund who was a perfect pianist, that created a complex. And complexes are extremely important. Every young person should have a complex if he’s talented—and his parents should take care of giving him it!—because sooner or later he must compensate for those complexes. That creates tension, and without that polarity, that tension between poles, nothing is born. In this case, the reason I wrote my First Piano Concerto twenty years after I came to the Academy was that I wanted to play it myself; I wrote it for my technique and for my hands, and I went around playing it with every orchestra that wanted to have me [Rautavaara’s First and Second Piano Concertos are on Ondine ODE 757-2]. I was very happy, but since then I have never wanted to play piano publicly. It was a compensation. I had shown that I could do that, that I was a pianist. These things happen. Another example would be when you are at school and there is always in the class that one guy who plays jazz marvelously; you know, whenever there’s a piano, he sits there and improvises jazz elegantly, beautifully. I was never him; I was one of the crowd around the piano, admiring. And thirty-five years later I wrote a work that was half comic opera, half musical called Apollo contra Marsyas, and that had a lot of jazz in it. And never since have I had any interest for jazz in my work. That was another compensation

“So to write is very interesting. You need all kinds of complexes and you need all kinds of skills—you need the two. I have always been very happy in that I knew what I wanted from the start: I wanted to be a professional composer, someone who makes his living from composing. And I have succeeded in doing that. I have written very much: I have a large output. That is to a large extent because I was curious. Curiosity is very important—I always try to get my students to be curious, to learn that they must experiment with everything, also the things they hate. When I was a professor at the Academy, I wanted the students to go along to the electronics studio and learn the basics of it all, even if they hated it and they didn’t believe in it. I told them that I didn’t think much of electronics. And then one day I had a commission from Denmark; they said they wanted a work with electronic music, orchestra and chorus. So I had to go and learn it, and since then I have been very interested. So you have to learn everything and then use what you use. But you cannot say that it’s trash. And there is so much to learn, there is so much to be improved, there is so much to experiment with. This is one of the reasons that my symphonies are so different.

“Since the eighties I feel somehow that I have ‘arrived,’ so that I am quite happy with what I do. Maybe that’s dangerous, but I have reached the stage where I don’t have to care! And I don’t have so much ambition any more. But I am very happy that I have done so much, that most of it is played, most of it is in the repertoire (also the avant garde things), and that I never did anything that I didn’t like.”

The First Symphony, completed in 1956 (and available with Nos. 2 and 3 on Ondine ODE 740-2), was premiered as the modernist grip on music was beginning to tighten and its echoes of Sibelius and Shostakovich did not please the critics. Kalevi Aho’s book offers a marvelously self-deprecatory quote from Rautavaara on his reaction to its cool reception:

I was given to understand, me, the white hope of Finnish music, personally chosen by Sibelius from the whole of the young generation to study in the States, that I was conservative! That would not do—I had to write a new symphony to show them!

But Rautavaara seems himself to have had some nagging doubts. “Maybe so. In 1988 I rewrote the First Symphony: I dropped two of the movements, so that it’s a two-movement symphony now; I tried to heighten some of the contrasts. When I was in my twenties I knew very little about myself, about my relationship to music and to the world. It was only forty years later that I could see what it was; I felt that Zeitgeist—I could still remember it very clearly. It was that very typical Zeitgeist for a young person (I mean my personal Zeitgeist), with two factors. One is a patheticism, being pathétique (every young person has to be pathétique). That is the first movement of the Symphony: it is large and rhetorical. The other factor is irony: you want to tear down those old structures and build something new—or at least tear them down. And that is the second movement: Shostakovichian, Prokofievan irony—it was very natural at that time.

“And it is natural to be influenced by whatever you hear when you are young. Very many of my ideas today were born in that period between twenty and thirty years of age. Right now they are producing a TV chamber opera based on a short story by O. Henry, the American writer who has these surprise endings. And when I was at New York, studying at the Juilliard School, my girlfriend found in a bookshop the collected short stories by O. Henry. When I read this very nice, sweet Christmas story, The Gift of the Magi, I immediately knew that I wanted to do it as a chamber opera. And now I have done it—in 1990. This kind of idea you can carry with you for years. Now I am working on this opera for Jorma Hynninen on Aleksis Kiivi (then what will probably come next will be a cello concerto for Arto Noras). The idea for the Kiivi opera began when Jorma Hynninen and I met in the airport here and talked for a few minutes, during which he said: ‘Don’t I look like Aleksis Kiivi?’ He had the beard and the profile, indeed. But the funny thing is that he had done this once before, in 1986, when he asked me: ‘Don’t I look like Vincent van Gogh? Wouldn’t that make a good opera?’ So I wrote Vincent for him [on Ondine ODE 750-2]. He forgot he had used that line before, but the fact is he does look like both of them. And they were similar characters, too: in his last years Kiivi became an example of the classic schizophrenic, as van Gogh also was. Basically, of course, crazy people are not very good subjects for a show, because it’s the simplest thing to do—that’s what children play, either drunkards or crazy people. But what is interesting about one kind of schizophrenic is this notion they have of a second reality. This is an idea that has been very central for me since I read a book by the scientist William James, who experimented with hallucinogenic drugs, LSD. He wrote that every time the person came out from the effect of the drug, the very first thing you wanted to tell was that the hallucination was so real, that it was the most real thing you’ve ever met, and that this reality is nothing compared to that. This happened over and over again to the subjects of his experiments. William James says it seems to be true that there are other realities around us, that there’s only the thinnest of screens between this world and that, and that taking those drugs is one possible way to open the window to that second reality. Then we have to think: What is music, really? When we talk about music, when we go to hear a pianist playing whatever classical repertoire, we may say, well, he’s got the style, he’s got the technique, but he doesn’t really understand it. What is it that is missing? I can’t tell you using any verbal means of expression. I can only do it by going to the piano and saying: This is how it should be. So the information in music is very exact, but it is not expressible in words, in concepts. It’s another reality, a very exact reality, but it has nothing to do with this reality, and it can’t be expressed in terms of this reality. That’s the trouble with writing about music: what you can say about a piece is entirely irrelevant to the music. It can be a symbol for it: you can say it’s happy or full of sorrow, or that it is in sonata-form, but all that means nothing. Really. You can speak about it, but you don’t speak about the music. Look at the musicological systems that have been devised, the Schenker analyses or those of the American Allen Forte and the group of people at Harvard. I taught that at the Academy, but then I stopped because I realized that it could only tell about the pitches, and even that didn’t tell anything about the music, because the rhythm wasn’t there, all the other elements of music but the pitches were absent—and the pitches are really secondary. When I was in my youth, I had to teach some children piano lessons, and so I tried an experiment. I played them…’!” Here Rautavaara intoned a rather expressionless, angular melody, not unlike a children’s song. “Then I tried this.” And he beat out a rhythm on the table with a coffee spoon. “And they all recognized it immediately as the March of the President—by the rhythm, not the pitches. So when you base a whole system wholly on the relationship of pitches, it is hopeless. It may be very interesting; Forte’s book about the details of The Rite of Spring is very interesting, but it doesn’t say anything musically.’“ I chance my arm: could it be that this kind of analysis follows historically from a style of composition where pitch is all important, that the analysis was developed to cope with music by composers like Webern and was then extended to earlier ones like Beethoven, where it is far less able to explain how the music has its effect? Rautavaara has a ready answer. ‘“You can analyse Webern; indeed, it’s very good to analyse Webern since he’s such a master of form. But take Varèse, a composer whose music is very much alike. It’s very hard to analyse: there’s no logic, so you cannot analyse it. The music is on the same theoretical level as Webern. But Webern has music and he has analysis; Varèse has only music.”

We have come a long way from Rautavaara’s Symphonies. Since we have been talking about Webern, Rautavaara’s strictly serial Fourth Symphony, Arabescata, seems a natural place to pick up the discussion. “Aho analyses the Fourth Symphony as a totally serial work, which it is, because I wanted to see what that was and if it was possible for me to create based on something as logical as that. Now I see that this logic is more from this world than from the world of music.” So was it a reaction against the Third Symphony, which sounds very much as if Bruckner had suddenly woken up in the middle of the twentieth century? Rautavaara pauses. “Well, I’d say that the Third Symphony was a logical vision of what I had been doing: the Second String Quartet, four years earlier, then the opera Kaivos (The Mine), my first opera. I see more and more clearly that, although the Third Symphony was based on a more or less classically dodecaphonic tone-row, it had the tendency to become more and more tonal. This combination of tone-row and tonal music—I have never met it anywhere else. When people say ‘Why do you use those methods?’, my answer has been that of Thomas Mann in Doktor Faust, where he makes Leverkühn say that music is so warm that it absolutely needs the strict law, it needs order; otherwise the warmth becomes a chaos. And historically that’s true, of course: this danger was felt by Schoenberg and so he invented dodecaphony.

“I studied a lot. I studied here, then I went to Vienna, to New York. I worked with Persichetti, with Sessions, with Copland, but still (probably I was too hard in the head) I felt that I didn’t master things, long-term pieces, formally. So I went to Wladimir Vogel in Switzerland. He was the twelve-tone master and taught me this technique at a moment when it was exactly what I needed. That stayed with me. It was something that I learned at a moment when I was so empty; it was placed in me, this idea that the music of our time, of this century, really is those twelve tempered tones, they are the material, and the question becomes how to use them, how to organize them. Then I was in Darmstadt, I studied Darmstadt composers’ work, and I experimented with them. But, as I told you earlier, I have never composed any music that I didn’t like, and therefore the music always turned out to be different from the ideals of Wladimir Vogel, different from Darmstadt. That was me.

“When I saw that the line was going in the direction of twelve-tone and tonality, as in the Third Symphony, I felt that I had not yet seen what there could be in modernism, in the avant garde of that time, the fifties and sixties.” So Rautavaara wrote the Third Symphony after studying with Wladimir Vogel? Such big-hearted music is a very strange response to a course of twelve-tone composition. “But the Third Symphony is based on a tone-row. Every note comes from that row. Of course, there are thirds and triads all the time. It begins with this romantic opening…” And he is already at the piano, playing first the opening of the Third, explaining its construction, picking out the notes of the row, then concealing them once more in the harmony. “Someone in Germany asked me why I did that. I said: ‘I need it. I don’t know what to do if I don’t have material which is strictly defined; I have to define my material and go from there. At the same time, this is inductive; it is deductive only when you consider the work as a totality.

“There were two versions of the Fourth Symphony, which were played, but I didn’t know what to do with them.” Indeed, Rautavaara was so unhappy about the Fourth Symphony that in 1985 he withdrew it from his symphonic catalog and replaced it with the serial Arabescata of 1962 which thereby became No. 4. “In fact, I thought of it as a symphony (there were four movements, for example) but I didn’t call it a symphony because you couldn’t call a piece ‘symphony’ in those days; it was an anachonism. So in Arabescata I really went though the thing from beginning to end strictly, to see what it could give to me. I quite accept that piece; it was a child of that time, perhaps, but I saw after writing it that this was nowhere to go. I would be only a programmer. I had a student at that time who made wonderful plans on bunches of paper, planned mathematically, acoustically, but then when he began to write the score, I said: That’s not interesting any more. The planning was the interesting thing; the idea, not the music, so I recommended that he go to the Polytechnic Institute instead!

“But then, after that, in the seventies there was a mixture, an amalgamation, a synthesis of those lines; and the eighties, when I started with operas again, a new aspect came along which was very exciting for me: writing the words, the libretto. There I had a very strange experience in synthesis. It happened twice, in two of those operas. I had been writing the libretto but hadn’t written the last act: I didn’t know what to do with it, especially in Vincent and then also in The House of the Sun, and so I started to compose it. I was already in the middle, in the second act, not knowing what would happen at the end. I had not a word, didn’t know anything about it—but I trusted that the music would tell me. And it did, and when I came to the third act I clearly saw what it should be. Jorma Hynninen knew about my problem. He was in New York, singing Wagner at the Metropolitan. He wrote a letter to me saying that there was this wonderful exhibition of the last paintings of van Gogh in the Metropolitan Museum and that ‘if you come here, you will find your last act’. So my wife and I went to New York immediately. We were there for only a few days but we saw that exhibition many, many times. And that was crucial. Seeing all those paintings—which I had seen many times in reproductions—in the original: they were radiating, emm, van Gogh. It was in the Metropolitan Museum that I solved the problem of the last act—should he shoot himself on stage, should he go off-stage and shoot himself? A friend of mine who had a gallery in New York said: ‘What are you going to do? I can’t see Jorma shooting himself on-stage or off-stage. And when you have a bang in the theater it sounds absurd.’ And then I went and saw all those paintings from his last years from his last period, in Arles, where he died: though he was sick, he was hopeless, he was desperate (he had sold one painting while he was there), he seemed to have no future, nobody cared about his art—and he was schizophrenic and they let him out from the lunatic asylum—the miracle was that these paintings were full of light, full of colors, full of anything but death and desperation, full of trust in life. They radiated such a strong nature—in contrast to the paintings of his youth, like those potato-eaters, which he did when he was still in Holland; they are very dark and mystical. But now, in his last days, it was a complete contrast. This is an example for those biographers or musicologists who infer from the situation of a composer, who say, for example, that Sibelius had this throat trouble or that some other composer was sick and therefore he wrote this terrible music which is so sad. It can be completely upside down: here we have a painter who had lost everything, who had lost all trust in life. And then I saw that this last act must be an apotheosis for his art, for life.

“With the next opera, The House of the Sun, I had written the libretto for the first and second acts, but again the end was missing. And somehow the music gave hints—I can’t explain how. When the music is like this, it must go on like that, in that direction, and so the music told me how the words must be. That was a very strange, mystical experience.”

The Fifth Symphony, composed in 1985, sits between the opera Thomas [Ondine ODE 704-2] and The House of the Sun. Does this succession mean that some of the musical concerns of the opera were carried on into the symphony, that there is a continuation of the same thinking? “Yes. The end of the symphony has some ideas I was using in the opera.” Thematic links? “No, just motifs. That happens very often. My feeling is that it’s such good music it should be heard twice! And then I feel that I should develop these things. Then there’s the same kind of relationship between Vincent and the Sixth Symphony, which is called Vincentiana [Ondine ODE 819-2]. I felt that these ideas wanted, needed symphonic treatment; I wanted to look at them from a symphonic aspect which was not bound by the dramaturgy or the libretto.

“As to the Seventh Symphony, I don’t think I would have composed it—at least, not at that time—without David Pickett, an American conductor who was here because he was going to conduct the Cantus Arcticus with his orchestra in Bloomington. He called me because he wanted to ask advice about the Cantus. Later we had some correspondence, and then he said that his orchestra was going to celebrate its twenty-fifth anniversary and would I write a piece for this occasion. I said, yes, but I am in the mood for not writing a short piece; if you want, I will write a symphony. They said yes, and they commissioned it. I couldn’t go to the performance because I was on the jury of a competition, but I heard a cassette and I had time to make changes. Then when Segerstam conducted it, it was partly a new version. It has been described being serene, as having the feeling that the music all the time knows where to go and goes there peacefully, with no real brouhaha, and arrives there. There are very strong moments, but the logic is very clear in a classical sense—not in the sense that there’s a given form that it falls into, rather that it searches for its own form and finds it. There’s a stability there. Maybe that’s the difference between this symphony and the previous ones.”

Does Rautavaara feel that there is a degree of continuity between the last three symphonies, particularly when contrasted with the stylistic leaps of the first three? “Yes. I feel that since the 1980s I have reached a ripe period—whatever that means (it sounds like death)! It’s the sense that I know what I want and I know how to achieve it, how to do it. And there is no hurry. When I had to make my living as a professor at the Sibelius Academy, it meant teaching, which could be very interesting, but it meant also meetings three or four times a week, with a pseudo-democratic arrangement where you say what you think and they do what they want anyway. That took many, many hours every week, and it was very hard. When I was young, I was aware of the difficulty of being a composer, so I thought I would be a tobacconist and run a tobacco shop (there were no sex shops at that time!), with a back room where I could work. And in summer there is nobody in Helsinki, so I could sit outside on the street with a chair and a dog by me and I could just write music—just to enjoy it and make my living by selling tobacco. Instead, it was teaching music. When I left the Academy, it was earlier than I had to, so I got out before I was completely senile, and now I can spend all my time doing music. And I have been very happy ever since, having all my time for myself. After Aleksis Kiivi, I have the cello concerto to think about, then I have a commission from Germany for a large work for chorus. Then what? Fortunately, these people, these institutions, they keep asking for music. You have the feeling that there’s a need for music. That’s been one of the most amazing things of my life: it’s such fun composing, and you can even be paid for it! It’s unbelievable! And I would do it anyway. I used to tell my students that the sign if a real composer is that, if he were put in a jail, knowing he would never be let out from there, even if he could never send letters or any other information from there, he would still compose. Not to exhibit himself or his work, but for himself, inside. Now I am fortunate that I have so many people asking for music that I can choose what I want to compose. So I take whatever I want, and that’s what I want to do anyway. That’s an ideal situation. Now I have written several operas. The one I am working on now is the fourth in a decade. But maybe I’ll go on: it’s fascinating, this combination of words and music. I have to hope that other people find it fascinating, too. I have been lucky that other people seem to like my music. I had a letter just two days ago from someone I had never heard of, but he just wanted to thank me for some pieces of mine he had heard. That’s great. If people come up to me in the street, if you come to interview me, that’s very good for the ego, but that’s not the important thing.”