It seems that the entire musical world has some memory of the gentle, warm and kindly man – and fabulous musician – who was André Previn. Since his path and mine crossed, too, I thought it worth recording my few memories of him, since even they, slight though they are, contribute to the general image of his easy-going generosity.

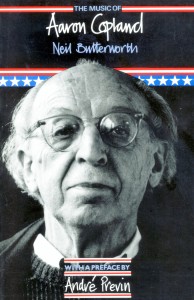

In the early 1980s, when I was nearly finished working on the text of Neil Butterworth’s The Music of Aaron Copland, I initially wrote to Leonard Bernstein to ask if he – as the conductor most directly associated with Copland’s music – might write a preface to the book. Word came back from his office that he would be happy to, and so a waiting game began, with the book completed but for the Bernstein intro. Every so often I would drop Bernstein’s office a line (by letter, of course, in those pre-e-mail days) until, a year later, someone rang me to say, sorry, but a note had been put in front of Bernstein and he had simply written ‘No’ in the margin. (I do have a copy of a letter from me to Bernstein somewhere in my files that begins ‘I was very sorry to miss your phone call this afternoon’, but at this distance I don’t have a clue what it might have been about.)

Frustrated, and with a wasted year under my belt, I turned to André Previn, his eleven-year chief conductorship of the LSO behind him but still then a UK resident, and easily then the most prominent American conductor alongside Lenny. I wrote to him on a Monday and the next day had a reply, putting us on first-name terms and asking me, since time pressed, to go along to his office (on Kensington Church Street, if I remember correctly) on Thursday, in two days’ time, where I would be able to pick up his text – this in the days of not only of physical letters but of two deliveries a day. After a year of Bernstein’s dithering, Previn’s calm efficiency was so striking that I felt guilty that I hadn’t asked him in the first place.

Among all the obituaries, Facebook postings and general effusions of amazement at both the profusion of Previn’s talent and the generosity of his personality, I’ve seen only one that referred to his ability as a writer. And yet

One of the many tales Previn recounts in the book is the customised version of ‘Call My Bluff’ he used to play with a couple of Hollywood friends, and he mentions that there was one word that used to reduce all three of them to helpless laughter, a word that means ‘any statue of a chicken’. In my review I wondered aloud what that word might be, and asked Previn in print that, if he ever read my review, whether he might get in touch and tell me what it was.

Some months, perhaps a year or so, after my review was published, Previn was conducting an LSO concert at the Barbican (Walton Viola Concerto with Yuri Bashmet, Brahms Fourth Symphony), and so I took the opportunity to go back stage to say hello and ask him what indeed was this word that reduced grown men to paroxystic mirth. Indeed, he hadn’t seen my review, and answered with genuine passion: ‘I can’t remember! There’s only one other of the three of us still alive and he can’t remember either. I’ve had about thirty letters from people asking what it was’.

That concert itself had illustrated Previn’s way with an audience. During the first movement of the Walton, one of Bashmet’s strings had snapped. He turned to the viola section, looked the huge instrument that Paul Silverthorne, the principal viola, was playing and, deciding against, grabbed a more conventionally sized one from the third desk, and finished the movement on it. Thereupon he disappeared into the wings to replace the broken string. He took an eternity, with Previn and the musicians idling onstage and all of us in the hall waiting and waiting and waiting. Eventually, Previn turned round to us in the audience and asked: ‘While we’re waiting, would you like to hear Mahler 2?’ The hall, of course, erupted with laughter.

Our paths next crossed in the Royal Festival Hall on 28 April 2002, on the occasion of the premiere, by Anne-Sophie Mutter (Mrs Previn No. 5 from 2002 to 2006, but friends and musical partners long before and after), of the fantasia Sur le même Accord by Henri Dutilleux; Kurt Masur conducted the London Philharmonic. I had to go backstage to give Anne-Sophie Mutter the score of a violin concerto I hoped she might perform – Orbis Factor by the Finnish composer Sakari Vainikka, which I had heard at the Tampere Biennale earlier that year. Whether she looked at it or not, I have no idea; I certainly heard no more about it – but the point, for this reminiscence, is that there was André, once of the best-known musicians of the world, doing his best to make himself invisible while everyone crowded around the evening’s soloist.

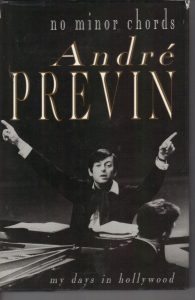

Some five or six years ago, I discovered to my amazement that No Minor Chords had been out of print for years, and so I wrote to André’s agent to offer the services of Toccata Press in making it available again; indeed, I continued, since (a) such a gifted writer must have written more than this one book, and (b) his 85th birthday was on the horizon, why didn’t we collect his writings as André Previn on Music and bring out an anthology to mark the event? She wrote back to say what a lovely idea it was, that André would be touched, and that she would speak to him and be back in touch. But she never did write back, and that’s the last I heard of the idea.