Volume One of the Martinů Early Orchestral Works series brought much satisfaction to all involved. Martin Anderson was delighted by the quality of the new album. Ian Hobson was rightly proud of his performances; members of Sinfonia Varsovia told him that this was great music and thanked him for the opportunity of playing it. Reviews were extremely positive, and I often felt the need to pinch myself; these obscure scores, which I had read about years before in Miloš Šafránek’s biography of Martinů, could now be heard and enjoyed, and I had helped in the process! Still, we could not afford to rest on our laurels; and we now had to enlist the support of another publishing house, Schott, in order to advance the project. Schott owns the rights to the four largest works in our project – the three ballets and Vanishing Midnight. Baerenreiter helped us make contact, and we shortly discovered that Schott had already taken the first steps towards publishing both one-act ballets. A Vorredaktion – a photocopy of the manuscript indicating the formatting of the eventual score – was available for each. Soon, I had the authority to procede, and started with what seemed to be the simplest of the three works – the ballet Stín (‘The Shadow’) from 1916.

On the face of it, The Shadow would be child’s play compared to the Little Dance Suite. The orchestra is much smaller (two of each woodwind, two horns, strings, harp, piano and celeste, an offstage soprano and two strokes on a triangle). The manuscript, with two systems per page almost throughout, has a fairly neat and orderly appearance – and besides, I had the Vorredaktion to guide me. This would be a sheer pleasure.

I will never again approach a Martinů manuscript in such an optimistic frame of mind. The Shadow teems with errors and inconsistencies and is sometimes utterly baffling. This last part of the blog will be a little more technical than the first two, since I would like to show you what is involved in preparing these pieces for performance. Martinů had presented The Shadow to the National Theatre in Prague, and it had been under consideration for some time until eventually rejected by Otakar Ostrčil. One can only imagine what teeth-gnashing and hair-tearing would have ensued if the work had been put into rehearsal. Perhaps Prague would have witnessed another defenestration! It would be impossible to list every problem I encountered; instead, I shall illustrate the main challenges with the aid of some printed examples and excerpts from the CD.

How should it be played?

The manuscript contains very little information on exactly how the themes should be played – whether notes should be smoothly linked together (slurs), played short and detached (staccato dots), and so on. Very often, Martinů indicates such ‘articulation’ at the beginning of the theme, but not thereafter. The piano theme which opens track 5 is a good illustration. You can hear it at Excerpt 1 below.

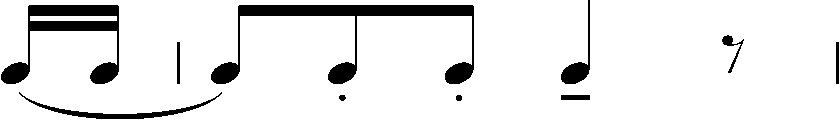

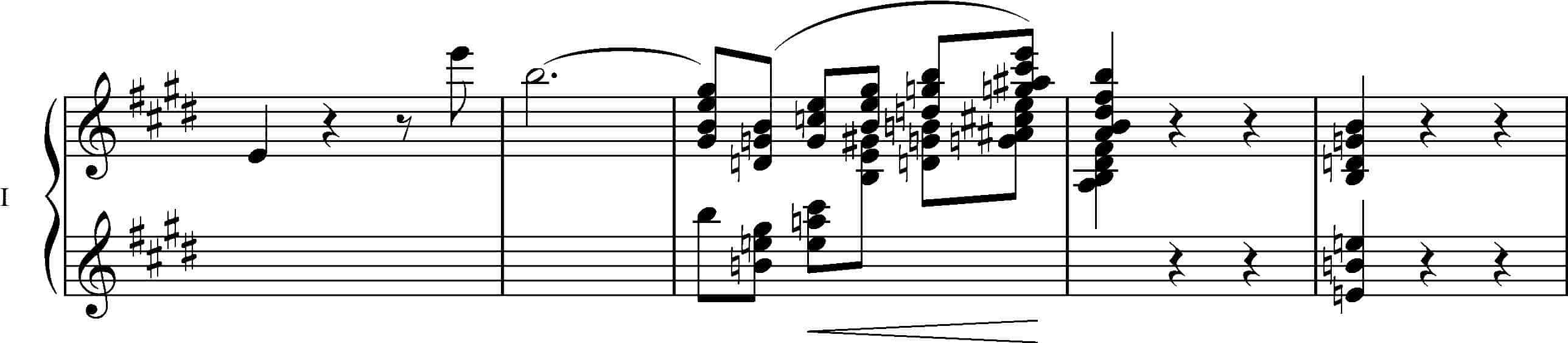

The staccato delivery of the first full bar is indicated by dotted notes in the manuscript, as in this example:

Example One

Further occurrences of this idea within the piano statement retain the slurs, but not the staccato dots. The same is true when the first violins take up the theme, though this time the first bar acquires a tenuto marking on the longer note (Example Two).

Example Two

Almost all other occurrences are undotted. It was tempting to go with the majority and leave just the slurs, but the staccato delivery seems right for this theme. After applying this articulation to the whole theme, it then became necessary to do the same with the woodwind continuation, and to the many accompanimental figures which have the same rhythm.

Similar problems arise with technical instructions, asking the players to modify the manner of playing in some way – for instance, asking strings to play pizzicato or woodwind players to flutter-tongue. Strictly speaking, these instructions remain in force until cancelled by a term such as nat., or by specific reference to a different technique (e.g., arco – bowed). But Martinů often omits the cancellation. In many cases, the nature of the writing makes it obvious where the cancellation should be – but not always. For instance, in the final struggle with Death, Martinů creates a mood of suspense, of menace, by marking all the strings tremolando sul ponticello (tremolando is an unmeasured succession of notes played very rapidly; sul ponticello asks the player to bow near the bridge of the instrument, producing a chilly, rasping sound). The tremolando terminates after sixteen bars – but should the ponticello continue? After eighteen bars, sul ponticello is marked again, meaning that a cancellation of the first ponticello should occur somewhere in the intervening bars – but there is more than one potential place, so Martinů’s precise intentions remain unclear.

Who Should Be Playing?

For much of the time, this question is easy to answer. The orchestra is small, shown in its entirety on the first page and clearly labelled. On subsequent pages, the size of the system (from top to bottom of the score) changes frequently – conventionally, instruments are omitted if they nothing to play for a long time. Additional labels usually clarify who’s doing what; but occasionally the manuscript becomes very confused. The lyrical, calm and radiant Lento (track 4) is the most taxing part of the work in this regard, even though the woodwind and horns have little to do; it is the division of labour amongst the strings that is extraordinarily difficult to determine. The string parts are on nine staves throughout, and I shall illustrate the problem by looking at the top two staves, both labelled first violin.

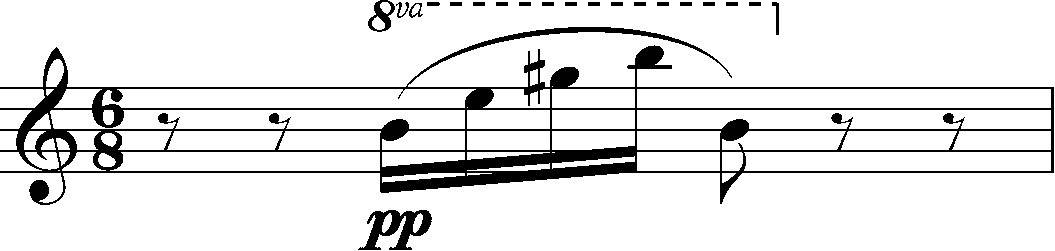

The upper of these two staves houses a prominent violin solo – the lower stave, two further soloists who form part of the accompaniment. All is clear for a number of bars until we run into the music in Example 3:

Example Three

It is obvious at first glance that something is wrong here. Three solo violins are unlikely to be able to cope with the demands of the third bar. Furthermore, it soon becomes clear (thanks to the ostensibly unnecessary accidentals) that the lower stave should be in bass clef. The whole thing would make sense on the piano, but the piano stopped playing before the end of the previous section and has not been indicated since. And if these bars are indeed for the piano, what are the first violins meant to be doing? Is their music to be taken from the second violin lines – and seconds from violas, and so on? Luckily, the passage is repeated later, confirming the piano hypothesis and dispelling some of the confusion over the strings. Nonetheless, the remainder of the Lento is a minefield of problems – the alternation between solo and tutti never made clear, the application and removal of mutes similarly vague.

What notes and rhythms should they be playing?

The very opening of The Shadow introduces a problem that persists throughout the score. The key is effectively G major, but Martinů has written no key-signature. All the F sharps must therefore be shown as accidentals. The initial horn and oboe solos are furnished with the necessary accidentals but as the oboe continues, F sharp becomes less and less frequent. The string accompaniment is likewise fairly callous in its attitude to the poor leading note. Thankfully, the composer’s true intentions are not hard to fathom at this point. Elsewhere, it can be trickier. The opening of Track 5 on the CD, which we have already heard once, is also a good illustration of this problem. Here is Excerpt 1 again if you need to refresh your memory:

Martinů’s manuscript abounds with all sorts of errors in this passage. Excerpt 2 below presents the music as originally written, free of all editorial interference by me, except in the matter of articulations. You will notice how:

- the violin solo gets ‘out of synch’ with everything else, twice changing note in the wrong bar before falling silent for a bar and then resuming.

- When the tutti first violins take over, they play a wrong note (B instead of E) in the second bar. Two bars later, they have semiquavers in place of quavers in the rhythm shown by Ex. 1, so that the bar does not ‘add up’.

- The woodwind continue with two four-bar phrases, over dominant-seventh chords in A and F respectively. The key signature is A major, so the flattened sevenths in the first phrase will need accidental naturals – which Martinů does not write!

In many of the difficult areas, melodic repetition and sequence afford valuable clues – but in one instance no additional pointers were available and a little re-composition was necessary. It occurs not long before the string Lento, in a deceptively simple passage where the oboe and horn answer each other. The passage ended up sounding like this:

Only the last two bars are problematic, as you will hear from this computer-generated original version. Something goes very badly wrong beneath the final horn-call:

What on earth has happened here? At first, the oboe is in F and the horn likewise. The second, quicker oboe call is in D. The horn imitates once more, but this times moves the melody down to D flat. However, the accompanying string chords have not taken the shift into account – they stay in D major (except the basses, who have unaccountably moved up to E natural!). It seemed that the only logical solution would be to have everything in D flat for the last statement. It makes a smooth transition to the slow waltz in F major that follows, but I admit that it is at complete odds with what the manuscript says.

And what key should it be in?

Martinů’s treatment of transposing instrument is notoriously slap-dash. In this score, only the horns and clarinets are transposing instruments, but there is still plenty of scope for error. This problem, I feel, remained with Martinů all his life – the published score of his last orchestral work Estampes is full of transposition errors in the clarinet part, and I feel fairly certain the mistakes originated with the composer. Such errors abound in The Shadow, alongside more calamitous mistakes which are difficult to understand. The clarinets, for instance, begin in A, but change to the B flat instrument on three occasions. Some of these changes are marked several bars away from where they should be. If the clarinets change instruments where marked, they will play a few bars a semitone higher or lower than intended, with excruciating results. There is even an instance in The Shadow of transposition in a non-transposing instrument! The passage occurs around 50 seconds into the Girl’s dance, and in the recording sounds like this:

In this passage, a short two-note rising figure is passed round twice between horn, flute, oboe, and clarinet. However, Martinů has copied the horn notation into the oboe part the first time round, effectively writing for the oboe as a transposing instrument in F and putting its entry at variance with all the others:

And what about the rhythm?

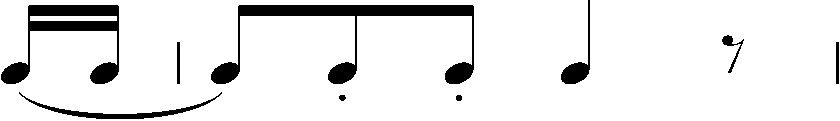

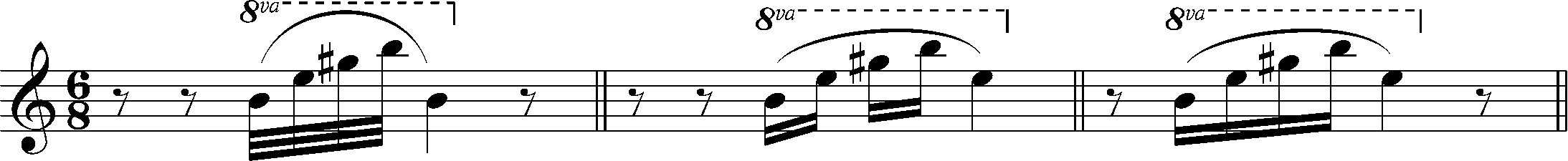

I have already mentioned a rhythmic deficiency when discussing Excerpt 2 above. It affects one bar only, but there are several other passages where a nonsensical rhythm is repeated time after time – for instance in the hornpipe-like music at the start of track 7:

Example Four

The punctuating flourishes on the piano are consistently written as in Ex. 4(a):

which adds up to seven quavers in a bar designed to hold six. Later on, the oboe inherits the same figure and the anomaly persists. The supporting string figuration is also ambiguous. Ex. 4(b) lists all the feasible alternatives:

As you may have detected, it was the last of these which prevailed.

I feel as though I have only just begun to describe the difficulties of this score, but this blog has almost certainly gone on too long as it is! Before taking leave of The Shadow, I must emphasise that all the nightmares it caused me have been worthwhile. The narrative of the ballet is somewhat gloomy, but Martinů has (completely inappropriately) fashioned a cheerful, beguiling set of dances to accompany it. Readers already familiar with H90 from Volume One may be intrigued to hear how the combination of harp, celeste and piano is put to a completely different use this time around – propulsive, spiky and Neo-Classical rather than glitteringly static. The Shadow contains many attractive melodies, some likely to take up permanent residence in the brain once they have been heard a few times.

My work in making this ballet available to the public has been made considerably easier thanks to the sharp eyes and proof-reading expertise of Ruth Sieber, formerly of Schott but now in retirement. Without her help, the performing materials would not be half as good as I believe they now are.

I finished my work on The Shadow over a year ago, and have since been engaged on the score of Vanishing Midnight — an extensive orchestral triptych written shortly before Martinů left for Paris. Only the central movement of this imposing work has ever been performed (and that merely twice). It is an astonishing work, poised, I feel, to be the supreme revelation of the entire series. The last movement (which co-incidentally is entitled ‘Shadows’) is an especially virtuosic tour de force – more ardent, passionate and enthralling that almost any other piece in Martinů’s early output. Its companions on disc are likely to be Dream of the Past and Ballad – performances which have already been recorded. I will soon turn my attention to the earlier ballet Night, written immediately before H90 and employing a similarly coruscating panoply of sounds. Although shorter than The Shadow, it poses a formidable challenge at every level. The note-setting alone will take an age: in addition to strings, standard brass and treble woodwind, the score calls for extensive percussion (keyed glockenspiel, xylophone, bass drum, cymbals, tam-tam, castanets and timpani), celeste, piano, three harps and a female choir behind the scenes). I shall soon begin to tackle this score and once more experience the sweetest pleasure this work has to offer – the notion that, for a few months at least, I will be the only person who has ever heard this music.

Fascinating reading and very interesting. How lucky the music world is to have someone so capable and dedicated to work through these scores. Eagerly awaiting hearing the CD.

I agree – very interesting reading!

It’s heartening to know that a composer as celebrated as Martinů experienced problematic areas (ie transposing instruments) and was prone to producing compositional inconsistencies.

The music on both Volumes is fascinating, especially for me as a newcomer to Martinů’s music, so I applaud all involved, and perhaps Mr Crump in particular, for pursuing this project in the face of obstacles which would put off other mere mortals. It is very much worthwhile and I do hope the music as well as the personnel involved in the recording get all the recognition they deserve.

I cannot thank you enough for bringing these early works to us. We are so fortunate to finally get a chance to hear them – and your pioneering work will be remembered for a long time. My biggest wish is to hear the complete 3 acts of Istar with the female choir (plus the late addition “Dance of the Priestesses” for Act 1). The Waldhans recording has intrigued me for a long time but it’s certainly time to hear the whole work without any cuts or arrangements. Best wishes for the rest of this project!

Thanks for your kind words. We have been hoping to record the whole of Istar but at the moment I am not sure if performing materials for the whole thing are available. Volume 3 is scheduled for recording in January and will include a long three-movement orchestral work called Vanishing Midnight, which is a work of real merit. I have also just finished my first draft of the score of another early ballet, Night, from 1912 – and am keeping my fingers crossed that it, too, will someday be recorded.